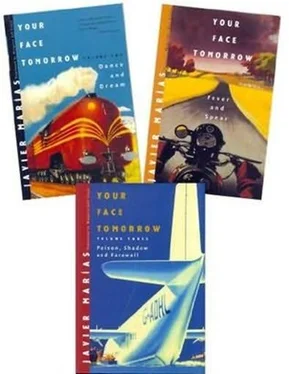

Javier Marias - Your Face Tomorrow 2 - Dance and Dream

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Javier Marias - Your Face Tomorrow 2 - Dance and Dream» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It occurred to me that when he made that last comment, he was thinking of Del Real, the treacherous friend whose future face, that of 1939, he had failed to foresee throughout the 1930’s.

'And did you ever meet the writer later on, in person?' I asked.

'Only very belatedly, thirty or forty years afterwards, at a couple of public events to which we were both invited. The first time, he was with his wife, and, of course, I shook his hand then so as not to wound or worry her in any way, and the three of us spoke briefly, about nothing really, just a polite exchange. The second time he was on his own, or, rather, with his usual entourage of admirers, he never went anywhere alone. He saw me and avoided me, avoided my eye. Not that I, heaven forbid, was trying to catch his. But just in case. You can always tell these things. He knew exactly who I was. I mean, not only what I did, or the fact that his wife and I had a very civilised friendship based on great mutual respect, I mean that he remembered my name from that morning in the cafe, and had, ever since then, been conscious that I'd heard his story. He must have regretted time and again letting his mouth or his smugness run away with him in that cafe. That's why I think it was perhaps the last time he revealed it to anyone, his disgusting contribution to that "bullfight". Antiguedad's reaction must have provided a warning. That and the ensuing silence. So you won't be surprised to learn that I never told your mother, however much I wanted to share the state of despondency in which I arrived home that day, even though I'd just received commissions for two translations. She had known Mares at university too and really liked him, well, almost everyone did, he was one of those people who light up any gathering and make it seem more promising and more worthwhile. Why bring her more grief, why afflict her with some new horror that could not be changed and for which there could be no solace and, of course, no compensation. Especially since she really liked bullfighting, much more than you might realise, a liking she inherited from her father, but one that she preferred not to pass on to you children. On more than one occasion, when we told you we were going to the theatre or the cinema, we actually went to the bulking.' And my father chuckled briefly to remember and to confess that small, innocuous deception. 'I didn't want to ruin bullfighting for her, because it doubtless would have. I myself didn't particularly enjoy bullfights, they left me pretty cold really, but it took a long time and a lot of effort on my part to prevent the story of Mares' death spoiling them for me entirely: at first, every fight we went to reminded me of him, and that cast a pall over the whole event, I felt his shadow slip in between me and each stage of the corrida. It's just the same, I suppose, as when I pass the corner of Alcala and Velazquez, I always think of the little child whom the militia-woman claimed to have killed by slamming against the wall.’

My father had grown tired, as I saw when he paused again; he closed his eyes as if they ached from having gazed for too long into the far distance. But it was not yet time for lunch; I glanced at my watch, it would be another twenty minutes before the woman who did the cooking came in to call us to the table or before my sister arrived, she'd said she would drop in and have lunch with us if she managed to finish what she had to do early. And he had not yet taken up the thread again; then, after a while, he decided to continue talking, although without immediately opening his eyes. 'I saw many things, we saw possibly worse things,' he said, using an ambiguous plural after that unequivocally singular T. 'Many simultaneous deaths, people I knew and didn't know, suddenly, during a bombardment, and then you don't have time to think about any of them, not even for a second, what tends to prevail is a sense that it's all over, a desire simply to give up, a feeling of being on the brink of extermination, that is what you feel then, and you're full of contrary impulses, wanting to survive at all costs, to simply step over the surrounding corpses, to seek shelter and save yourself, but also to stay with them, I mean to join them, to lie down by their side and form part of the inert pile of bodies and stay there; it's a feeling almost akin to envy. It's odd, but even in the din and the collapsing buildings and the chaos, as you're racing to help someone who's wounded or to protect yourself, you know at once when someone's a hopeless case. Not a threat to anyone, but at peace, at rest, gone in a flash. It's likely, in fact, that if you followed the second impulse, you would unintentionally achieve the same effect as the first, because the next bomb would never fall in the same place as the previous ones: the besiegers didn't squander their bombs, the safest place might well be alongside the already dead. But, as you see, I've told you about two things that I didn't see, that we didn't see, but which were recounted to me or, rather, which I happened to hear, in neither case were the words addressed to me personally, or at least not exclusively; and yet they've stayed in my memory as clearly as if I had seen it myself, possibly more clearly, it's easier to suppress an unbearable image than it is to suppress someone's account of an event, however loathsome those events might be, precisely because narrative always seems more bearable. And in a sense it is: what you see is happening; what you hear has happened already; whatever it is, you know that it is over, otherwise no one would be able to tell you about it. I believe that the reason I have such a vivid memory of those two stories, those two crimes, is because I heard them from the mouths of the people who had committed them. Not from a witness, not from a victim who had survived, whose tone would have been one of justifiable reproach and complaint, but also, therefore, of a more dubious veracity, there is always a tendency to exaggerate any description of suffering, because the person who endured it tends to present it as a virtue or as something to be admired, a noble sacrifice, when sometimes that isn't the case at all and it was just bad luck. Both of the people who told the stories did so unhesitatingly and boastfully. Yes, they were showing off. To me, though, it was as if they were accusing themselves and without even having been asked to do so, the Falangist writer and the woman on the tram. That, at least, is how my ears reacted, they were not amused, they did not admire the cruel acts they described, but were horrified and disgusted; and my judgement condemned them, passively of course.' ('With my tongue silenced," I thought.) 'It gives you an idea of how other people experience violence; of how simpler, more superficial people – although they're not necessarily more primitive or less educated – grow accustomed to it and then see no need to place limits on it and consequently don't; and it gives you an idea of just how much violence there was. So much, and so taken for granted, that the people who perpetrated the most brutal and gratuitous acts of violence, committed out of a senseless, baseless hatred, could talk about it in public with perfect aplomb, could boast about it. I mean what possible need was there to bash a baby's brains out; what need was there to stick banderillas and lances into a condemned man and then mutilate his body. But there were others among us who never got used to it, you never do if you keep your sense of perspective and don't fell into the lazy way of thinking that says "What does it matter, after all…" which lay behind the comment that other man made to the writer when he asked if the malagueno had claimed the other ear and the tail too "while he was at it", if you refuse to allow the concrete to become abstract, which is what happens today with so many people, starting with terrorists and followed soon after by governments: they don't see the concreteness of what they set in motion, nor, of course, do they want to. I don't know, it seems to me that most people in these societies of ours have seen too much violence, fictitious or real, on the screen. And that confuses them, they accept it as a lesser evil, as not being of great importance. But neither fictitious nor real violence is real on screen, as a flat image, however terrible the events we're shown. Not even on the news. "Oh, how terrible, that really happened," we think, "but not here, not in my room." If it were happening in our living room, what a difference that would make: feeling it, breathing it, smelling it, because there is always a smell, it always smells. The terror, the panic. People would find it unbearable, they would really feel the fear, their own and other people's, the effect and the shock of both are similar, and nothing is as contagious as fear. People would run away to take shelter. Look, all it takes is for someone to give someone else a shove, in a bar, say, or in the street or in the metro, or for two uncouth motorists to come to blows or to grapple with each other, for those nearby to tremble with shock and uncertainty, for them to grow tense and filled with often uncontrollable alarm, both physical and mental, it happens to most people. Worse still if there's a crowd. And if you punch someone really hard, you'll probably do them quite a lot of damage, but your own hand will be a mess too and will be inflamed for several days afterwards. After just one blow with the fist. It's no joke.' ('That's true,' I thought, but didn't say anything so as not to worry him, 'it happened to me once, and I could hardly move my hand afterwards.') 'Anyone who, at some stage in his life, has lived with violence on a daily basis will never take any risks with it, never take it lightly. He'll administer it not just with care and with extreme caution, but in as stingy and miserly a way as he can. He won't allow himself to be violent, not as long as he can avoid it, and it almost always is avoidable, although he'll be able to withstand it better should violence ever return.' Then my father opened his pale eyes again, and they were once more serene; they had been troubled by all those memories. 'Apart from in fiction, that's different, although people should be more aware of that than they are. Exaggerated violence is even funny, watching film violence is like watching acrobatics or fireworks, it makes me laugh, all those bodies sent flying, all that blood spattered about, you can see a mile off that they're wearing springs and bags of liquid that they puncture and burst. People who are shot in real life don't leap into the air, they just drop and cease moving. That kind of violence is perfectly innocuous or, at least, it would be if there hadn't been such a decline in people's general levels of perceptiveness. For someone as ancient as me, it's astonishing to see how stupid the world has become. Inexplicable. What an age of decline, you have no idea. Not just intellectual decline, but a decline in discernment too. Oh well. That kind of violence is not much different from the beatings described in Don Quixote or the ones shown in those Tom and Jerry cartoons you enjoyed so much as children, when you know deep down that no one has been badly hurt, that they'll get up afterwards unscathed and go out to supper together like good friends. There's no need to get all puritanical about it, or prudish for that matter, like those people who reduce the classics to pure saccharine. With real violence, on the other hand, you must take no chances. But look how things have changed, and attitudes too: when war was declared on Hitler, and it may be that there has never been an occasion when a war was more necessary or more justifiable, Churchill himself wrote that the mere fact of having come to that pass, to that state of failure, made those responsible, however honourable their motives, blameworthy before History. He was referring to the governments of his own country and of France, you understand, and, by extension, to himself, although he would have preferred that state of blameworthiness and failure to have been reached at a much earlier stage, when the situation was less disadvantageous to them and when it would not have been so difficult or so bloody to fight that war. "… this sad tale of wrong judgements formed by well-meaning and capable people…": that is how he described it. And now, as you see, the same people who are scandalised by the rough and tumble of Tom and Jerry et al. unleash unnecessary, selfish wars, devoid of any honourable motives, and which sidestep all the other options, if they don't actually torpedo them. And unlike Churchill, they are not even ashamed of them. They're not even sorry. Nor, of course, do they apologise, people just don't do that nowadays… In Spain, the Francoists established that particular school of thought long ago. They have never apologised, not one of them, and they, too, unleashed a totally unnecessary war. The worst of all possible wars. And with the immediate collaboration of many of their opponents… It was absurd, all of it.' I realised that now my father was thinking out loud, rather than talking to me, and these were doubtless thoughts he had been having since 1936 and, who knows, possibly every day, in much the same way as not a day or a night passes without our imagining at some point the idea or the image of our dearest dead ones, however much time has passed since we said goodbye to them or they to us: 'Farewell, wit; farewell, charm; farewell, dear, delightful friends; for I am dying and hope to see you soon, happily installed in the other life.' And in the thought that followed he used a word which I heard Wheeler use later on, when talking about wars, although he had said it in English, and the word was, if I'm not mistaken, 'waste'. 'And what a terrible waste… I don't know, I remember it and I can't believe it. Sometimes, it seems unbelievable to me that I lived through all of that. I just can't see the reason for it, that's the worst of it, and with the passing of the years, it's even harder to see a reason. Nothing serious ever appears quite so serious with the passing of time. Certainly not serious enough to start a war over, wars always seem so out of proportion when viewed in retrospect… And certainly never serious enough for anyone to kill another person.' (And then even our sharpest, most sympathetic judgements will be dubbed futile and ingenuous. Why did she do that, they will say of you, why so much fuss and why the quickening pulse, why the trembling, why the somersaulting heart? And of me they will say: Why did he speak or not speak, why did he wait so long and so faithfully, why that dizziness, those doubts, that torment, why did he take those particular steps and why so many? And of us both they will say: Why all that conflict and struggle, why did they fight instead of just looking and staying still, why were they unable to meet or to go on seeing each other, and why so much sleep, so many dreams, and why that scratch, my pain, my word, your fever, the dance, and all those doubts, all that torment?)

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.