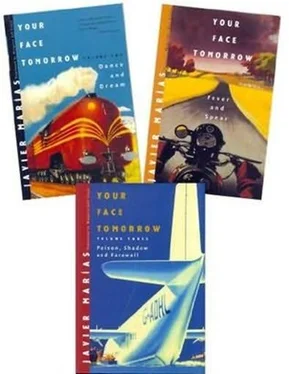

Javier Marias - Your Face Tomorrow 2 - Dance and Dream

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Javier Marias - Your Face Tomorrow 2 - Dance and Dream» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

'A bargain,' I said. And, just in case, I added: 'Or a stroke of luck.’

But I didn't like the man's second irritable outburst at all. It wasn't that I felt affronted or bullied. Well, I did, but that didn't matter, I was not what I was ('I am not what I am,' I would sometimes repeat to myself, 'not entirely,' I would think, 'not exactly') when I went out with Reresby or with Ure or Dundas, not even when I accompanied Tupra, alone or with the others; in a sense, I simply played the role of subaltern or subordinate – which, at bottom, I was, given the circumstances and certainly as long as I remained tied to my paid activities and kept my nameless post – or the role perhaps of escort or acolyte – which I never was in any way at all – and I did not take personally any slights to which my character might occasionally be subject, because I received them – how can I put it – on behalf of the whole group and as a mere part of it, the most recent and belated and insignificant part; and the entire group seemed to me, in turn, fictitious, or, rather, devoted to fictions, perhaps that would be more exact. And the fact that almost everything happened in a foreign language only emphasised the artificial, unreal, make-believe nature of what was said and done: in another language you cannot help but feel that you are always acting or even translating (however well you know the language), as if the words you pronounce and hear belonged to some absent person, to a single author who invented and dictated them and had already distributed the parts, and then nothing that anyone says to you makes much of a mark. How much more difficult it is, on the other hand, to bear the reproaches and humiliations and insults that we hear in our own language, which are so much more real. (Maybe they are the only real slights, which is why it would be best to nip in the bud any possible slights Perez Nuix might deal out; to prevent their even being born so that they would not grieve me and so that I could not store them away. Like those I had received from Luisa, which still resonated, possibly because now there was almost nothing to dissipate or soften them, and she was ever more taciturn with me when we spoke on the phone.) Besides, that night would eventually end, and I would more than likely never see Manoia again, and so I didn't mind if my ‘I’ of that evening or of any other spent in the service of Tupra – myself as Jack, let's say – should feel momentarily, and as it were vicariously, discomfited. My ‘I’ of before that and after was not Jack, but Jacques or Jacobo or Jaime, and that ‘I’ was stricter and prouder and also more vengeful, while the former could not help but see all the events he witnessed or took part in as slightly pointless and false, as if they did not really concern Jacques or did not happen to him, and as if he were protected from them. The reason I so disliked Manoia's reaction was because it alarmed me sufficiently to feel suddenly implicated, at least in my role as Jack, as a negligent and possibly even failed chevalier servant. I realised that his rudeness must have some other cause than my slowness and my hesitancy (or my incompetence, if I was wrong about the stroke of luck and the bargain). It was doubtless to do with Mrs Manoia, and at that precise moment I glanced over at the Spanish table, after an interval of no more than twenty seconds, and De la Garza and Flavia were no longer there.

I looked anxiously around. I had missed the moment when they had left the table, the others were all there, including the trite writer (clapping more furiously now, and looking even more the stereotypical flamenco artiste) and the lacklustre heiress with the invariable expression on her face of someone being forced to breathe the foul odours of some very slow-moving effluvia, which meant that neither the group nor even a part of the group had decamped to somewhere more amusing, only my lady and the attache had absented themselves. The disco was a big place and I could see only a small part of it, they could have moved to any of the numerous bars, or gone on to the more distant and more frenetic dance floors; but they might also have become shadows in some dark corner or – although I refused even to imagine this – abandoned the club, together, with unnatural urgency and without saying goodbye. 'No, that's impossible,' I thought, not as yet seriously worried; 'Tupra said that all she wanted were compliments and gallant remarks, and that, however eager she might seem to follow a particular path to its end, she would not take that one first poisoned step forwards, and Tupra is rarely wrong. Tonight, however, the lady, it is true, has had a number of drinks, and it would be best not even to begin to calculate De la Garza's liquid intake. And who has not taken such a step at some point in their existence, in the company of an idiot or a criminal or a monster, no one is safe. But Rafita. With his hairnet. With his enormous pale jacket. With his earring like something a female Cuban singer or a Puerto Rican dancer would wear. As if he were Rita Moreno in West Side Story. With his failed Negroid air. So much poison would be suicide, and surely no one would botch his own suicide with such a display of bad taste.' My feelings of apprehension grew, however, when I remembered in my own lifetime certain ineffable couplings I had witnessed, as well as being reliably informed of other aberrant pro tern pairings ('one-night stands' they're called in English, a term that has its origins in the theatre and denotes, in my view, a mixture of narcissism and exhibitionism).

Reresby and Manoia immediately noticed my unease. The latter shot a rapid glance at the empty space left by the vanished couple, he remained impassive and did not even touch his glasses, but I felt him grow suddenly dark, he raised his hands as was his custom, holding them in that uncomfortable suspended position reminiscent of certain pious poses, one hand on top of the other in the air, elbows or forearms resting on nothing; I found those hands threatening, bony, rigid – his fingers like yellowing piano keys – as if they were gathering strength or perhaps calm; as if they were preparing themselves or holding back or mutually keeping each other down. Tupra, however, never showed such visible signs of religiosity or piety in any unconscious gesture or posture, not a trace, not even in the cruel form that religiosity often adopts. There was nothing about him of the poseur or even the dissembler, he wasn't like that: if he often seemed opaque and indecipherable it was not because of any non-existent posturings, but simply because it was impossible to know all his codes. (I hoped that he had much the same experience with me, more or less: it would be better for me if he did.) Tupra could tolerate silence all too well, his own, that is, any silence that depended solely on him, any voluntary silence, and anyone who is happy to remain silent wreaks havoc on the impatient and the loquacious, and on his adversaries. That is why I hoped he would speak soon and dissemble a little when he did so (a little and badly, and only for a moment). He hooked one thumb in the chest pocket of his waistcoat in order to appear relaxed: although this was not an unfamiliar gesture in him and resembled one of Wheeler's gestures too, perhaps he had copied the latter, in fact, the more usual pose in both was to hook one thumb under one armpit as if they were carrying a riding crop and resting the whole weight of their chest on it, that, at least, was the impression. And then, half turning towards me, he said in a rapid murmur (and it was clear to me that the reason he spoke to me in this way, swiftly and under his breath, was to prevent his guest from hearing his words): 'First of all, Jack, if you wouldn't mind, take a look in the toilets, both the Ladies and the Gents. Oh, and in the toilet for cripples as well, which tends to be free. Be so kind as to find her

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.