In the man in the Prado I could see nothing of this, by which I mean his sexual voracity, although his gaze was intently fixed on a painting depicting a woman, a mother. Perhaps he had given her the once-over too, prior to any artistic, pictorial or even technical appraisal. Perhaps he had been put off by the fact that the woman appeared in the painting with her three small children; although not necessarily, if he was Custardoy, given that he was clearly attracted to Luisa and she, after all, was a mother of two. (True, the woman in the painting was a rather unattractive, matronly type, whereas Luisa kept herself very slim and, to my eyes, pretty and youthful, but I don't know how she appears to other eyes.) What I had noticed right from the very first instant was that he was wearing a jacket and tie and black lace-up shoes. They wouldn't have been made by Grenson or Edward Green, but they were plain and in good taste, with soles that were neither thick nor made of rubber, I couldn't object to his choice of clothes, except to say that they were too conventional. Not the ponytail, of course, although in recent years, that's become fairly common among men of any age (age no longer acts as a brake on anything and has lost the battle against fashion and vanity). It gave him a roguish look, which was the adjective Cristina had so aptly used to describe him, if indeed it was him.

Once when I walked past, always keeping a prudent distance so that he wouldn't notice me, I managed to confirm my first impression: he was making sketches of the four heads in the painting and, at the same time, taking notes, both at great speed. If he was Custardoy, he might have been commissioned to make a copy and was carrying out a preliminary study. Or, if he really was as good as they said, perhaps he didn't need to stand in front of the picture itself with easel and brushes for long hours and even longer days, and it was enough for him to capture and memorize it (maybe he had a photographic memory) and then work from a good reproduction in his studio, the fact is I know nothing about the techniques used by copyists, let alone forgers (he wouldn't be creating a forgery on this occasion, no one would believe that the work in the Prado wasn't authentic, wasn't the original).

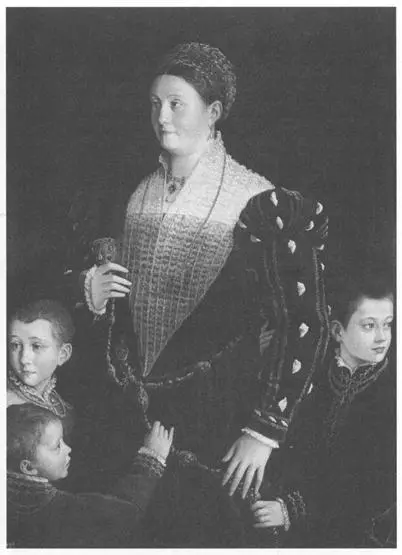

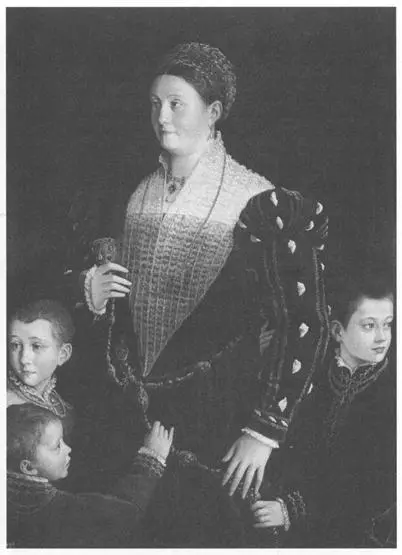

However, I didn't want to spend too much time in his vicinity: the longer I stayed there like his shadow, the greater the risk that he would turn around or glance to his left and see me there, although it was highly unlikely that he would know me or recognize me from photos Luisa might have shown him, though I doubted that she had, and the probability was that he had never seen me. Anyway, I moved away a little and looked briefly at another painting, "Messer Marsilio Cassoti and His Wife" by Lorenzo Lotto, and then shifted closer again, I didn't want him to escape me now, to lose track of him; I ventured slightly further off and had a quick look at a "Portrait of a Gentleman" by Volterra, but was drawn back at once to the man with the pony-tail, I didn't dare take my eyes off him for more than a few seconds; I wandered away again and studied Yahez de la Almedina's "St. Catherine"-all in reds and blues, resting a long sword on the wheel of her martyrdom-and that figure distracted me, so much so that after only half a minute's contemplation, I started in alarm and almost ran back to the painting of the mother and her children. In between all these comings and goings and periods of waiting, I managed to get a good look at that painting: it was average size, about three feet something long by three feet wide I reckoned; and the painting was a family portrait, according to the label, "Camilla Gonzaga, Countess of San Secondo, and her Sons" by Parmigianino, whose real name, I noticed, was Mazzola, like a famous soccer star from my early childhood who played against the Real Madrid of Di Stefano and Gento, I seemed to recall he was a forward with Inter Milan. Against a dark almost black background stood the sturdy Countess, well dressed, discreetly bejewelled, holding in her right hand a golden, gem-incrusted goblet which looked slightly out of place

with so many children around her; or perhaps it wasn't a goblet, but the large tassel from her belt. She bordered on the plump, or maybe not (but she was certainly wide), her expression was rather absent and certainly not lively, although there was perhaps a remnant there of calm almost indifferent determination. She had slightly bovine, almost prominent eyes, very fine eyebrows, which looked as if they had been penciled in, and rather thin and unalluring lips; her best feature was possibly her lustrous un-lined rosy skin, so smooth and taut on her cheeks that it looked as if it might burst. More surprising was her lack of interest in her children, Troilo, Ippolito and Federico according to the label; she showed no signs at all that she was devoted to them, she wasn't looking at them or touching them, not even holding the hand of the child to her left, which was very close to her own inert left hand. The Countess was like an astonished statue surrounded by other smaller but similarly self-absorbed statues, because the odd thing was that the children weren't paying her any attention either, although two of them were distractedly clasping the braided belt of her dress. Each figure was gazing out of the picture in a different direction as if each and every one of them was far more interested in people or elements beyond the frame than in each other in the case of the boys, or in her sons, in the case of the mother, who was the central figure. The oldest child on the right was the least attractive and resembled a foundling or an orphan, partly because of his ugly and excessively severe haircut, and partly because of the sad expression on his face; the youngest didn't seem very happy or very affectionate either, just vulnerable, and about to tug at his mother's belt like someone performing a purely reflex or habitual action; the boy on her left, the prettiest of the children and the one with the most alert eyes, seemed completely oblivious to the rest of the group, as if he were anxious to escape both the others and the enforced patience of his extreme youth.

The only gaze that one could follow or imagine was that of the Countess, given that, to her right, beyond the high door, which kept them still further apart (a whim of that month's reorganization), hung the portrait of her husband, at whom she was directing that distinctly chilly and possibly disappointed look, or perhaps it was a look that was wounded by the mere thought of him. 'They were painted separately,' I thought, 'husband and father on one side, wife and mother with the children on the other, two different portraits, in two distinct, isolated spaces rather than in one space common to them both: a bit like my now living alone in London, while Luisa stays here in Madrid with Guillermo and Marina, except that she's devoted to our children and they to her, at least that's how it has been up until now, it would be terrible if that Custardoy fellow were beginning to distance her from them, it happens with women sometimes, they suddenly have eyes and thoughts only for the new man they're chasing or for the old love they're losing-that's the only thing that can, very occasionally, create a rift and cause them temporarily to relegate their children to second place, just as the Countess perhaps has her gaze fixed on the distant soldier who is out of the picture and perhaps out of time, thus neglecting Troilo, Ippolito and Federico, who are accustomed now to the fact that their mother barely pays them any attention and lives obsessed with thoughts of her absent husband and perhaps sees them as a tie and an impediment and a hindrance, I don't think such a thing would ever happen with Luisa, although she does seem to have made frequent use of the Polish babysitter while I've been here, and there must be or could be a reason for that. And Luisa is clearly not obsessed with thoughts of me, however absent I might be. She, after all, was the one to expel me from her time and from the children's time, although I doubtless gave her some cause to do so.'

Читать дальше