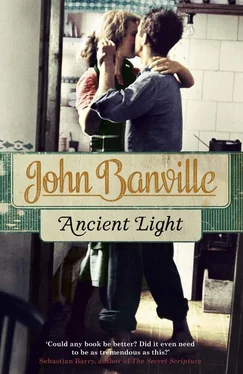

John Banville - Ancient Light

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Banville - Ancient Light» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: Viking Penguin, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ancient Light

- Автор:

- Издательство:Viking Penguin

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-670-92061-7

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ancient Light: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ancient Light»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

gives us a brilliant, profoundly moving new novel about an actor in the twilight of his life and his career: a meditation on love and loss, and on the inscrutable immediacy of the past in our present lives. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tq-oMYIS44o

Ancient Light — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ancient Light», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It was by the coast too that our daughter died, another coast, at Portovenere, which is, if you do not know it, an ancient Ligurian seaport at the tip of a spit of land stretching out into the Gulf of Genoa, opposite Lerici, where the poet Shelley drowned. The Romans knew it as Portus Veneris, for long ago there was a shrine to that charming goddess on the drear promontory where now stands the church of St Peter the Apostle. Byzantium harboured its fleet in the bay at Portovenere. The glory is long faded, and it is now a faintly melancholy, salt-bleached town, much favoured by tourists and wedding parties. When we were shown our daughter in the mortuary she had no features: St Peter’s rocks and the sea’s waves had erased them and left her in faceless anonymity. But it was she, sure enough, there was no doubting it, despite her mother’s desperate hope of a mistaken identity.

Why Cass should be in Liguria, of all places, we never discovered. She was twenty-seven, and something of a scholar, though erratic—she had suffered since childhood from Mandelbaum’s syndrome, a rare defect of the mind. What may one know of another, even when it is one’s own daughter? A clever man whose name I have forgotten—my memory has become a sieve—put the poser: what is the length of a coastline? It seems a simple enough challenge, readily met, by a professional surveyor, say, with his spyglass and tape measure. But reflect a moment. How finely calibrated must the tape measure be to deal with all those nooks and crannies? And nooks have nooks, and crannies crannies, ad infinitum , or ad at least that indefinite boundary where matter, so-called, shades off seamlessly into thin air. Similarly, with the dimensions of a life it is a case of stopping at some certain level and saying this, this was she, though knowing of course that it was not.

She was pregnant when she died. This was a shock for us, her parents, an after-shock of the calamity of her death. I should like to know who the father was, the father not-to-be; yes, that is something I should very much like to know.

The mysterious movie woman called back, and this time I was first to get to the phone, hurrying down the stairs from the attic with my knees going like elbows—I had not been aware I was so eager, and felt a little ashamed of myself. Her name, she told me, was Marcy Meriwether, and she was calling from Carver City on the coast of California. Not young, with a smoker’s voice. She asked if she was speaking personally with Mr Alexander Cleave the actor. I was wondering if someone of my acquaintance had set me up for a hoax—theatre folk have a distressing fondness for hoaxes. She sounded peeved that I had not returned her original call. I hastened to explain that my wife had not caught her name, which prompted Ms Meriwether to spell it for me, in a tone of jaded irony, indicating either that she did not believe my excuse—it had sounded limp and unlikely even to me—or just that she was tired of having to spell her mellifluous but faintly risible moniker for people too inattentive or dubious to have registered it properly the first time round. She is an executive, an important one, I feel sure, with Pentagram Pictures, an independent studio which is to make a film based on the life of one Axel Vander. This name too she spelled for me, slowly, as if by now she had decided she was dealing with a halfwit, which is understandable in a person who has spent her working life among actors. I confessed I did not know who Axel Vander is, or was, but this she brushed aside as of no importance, and said she would send me material on him. Saying it, she gave a dry laugh, I do not know why. The film is to be called The Invention of the Past , not a very catchy title, I thought, though I did not say so. It is to be directed by Toby Taggart. This announcement was followed by a large and waiting silence, which it was obvious I was expected to fill, but could not, for I had never heard of Toby Taggart either.

I thought that by now Ms Meriwether would be ready to give up on a person as ill-informed as I clearly am, but on the contrary she assured me that everyone involved in the project was very excited at the prospect of working with me, very excited, and that of course I had been the first and obvious choice for the part. I purred dutifully in appreciation of this flattery, then mentioned, with diffidence but not, I judged, apologetically, that I had never before worked in film. Was that a quick intake of breath I heard on the line? Is it possible a film person of long experience as Ms Meriwether must be would not know such a thing about an actor to whom she was offering a leading part? That was fine, she said, just fine; in fact Toby wanted someone new to the screen, a fresh face—mark, I am in my sixties—an assertion that I could tell she no more believed in than I did. Then, with an abruptness that left me blinking, she hung up. The last I heard of her, as the receiver was falling into its cradle, was the beginning of a bout of coughing, raucous and juicy. Again I wondered uneasily if it was all a prank, but decided, on no good evidence, that it was not.

Axel Vander. So.

___

Mrs Gray and I had our first—what shall I call it? Our first encounter? That makes it sound too intimate and immediate—since after all it was not an encounter in the flesh—and at the same time too prosaic. Whatever it was, we had it one watercolour April day of gusts and sudden rain and vast, rinsed skies. Yes, another April; in a way, in this story, it is always April. I was a raw boy of fifteen by then and Mrs Gray was a married woman in the ripeness of her middle thirties. Our town, I thought, had surely never known such a liaison, though probably I was wrong, there being nothing that has not happened already, except what happened in Eden, at the catastrophic outset of everything. Not that the town came to know of it for a long time, and might never have found out had it not been for a certain busybody’s prurience and insatiable nosiness. But here is what I remember, here is what I retain.

I hesitate, aware of a constraint, as if the prudish past were plucking at my sleeve to forestall me. Yet that day’s little dalliance—there is the word!—was child’s play compared with what was to come later.

Anyway, here goes.

Lord, I feel fifteen again.

It was not a Saturday, certainly not a Sunday, so it must have been a holiday, or a holyday—the Feast of St Priapus, perhaps—but at any rate there was no school, and I had called at the house for Billy. We had a plan to go somewhere, to do something. In the little gravelled square where the Grays lived the cherry trees were shivering in the wind and sinuous streels of cherry blossom were rolling along the pavements like so many pale-pink feather boas. The flying clouds, smoke-grey and molten silver, had great gashes in them where the damp-blue sky shone through, and busy little birds darted swiftly here and there or settled on the ridges of the roofs in huddled rows, fluffing up their feathers and carrying on a ribald chattering and piping. Billy let me in. He was not ready, as usual. He was half dressed, in shirt and pullover, but still had on striped pyjama bottoms and was barefoot, and gave off the woolly odour of an unfresh bed. He led the way upstairs to the living room.

In those days, when no one but the very rich could afford to have central heating, our houses on spring mornings such as this one had a special chill that gave a sharp, lacquered edge to everything, as if the air had turned to waterglass overnight. Billy went off to finish dressing and I stood in the middle of the floor, being nothing much, hardly even myself. There are moments like that, when one slips into neutral, as it were, not caring about anything, often not noticing, often not really being , in any vital sense. My mood that morning was not one of absence, however, not quite, but of passive receptivity, as I think now, a state of not quite conscious waiting. The metal-framed oblong windows here, all shine and sky, were too bright to sustain my gaze, and I turned from them and cast idly about the room. How quick with portent they always seem, the things in rooms that are not ours: that chintz-covered armchair braced somehow and as if about to clamber angrily to its feet; that floor-lamp keeping so still and hiding its face under a coolie’s hat; the upright piano, its lid greyed by an immaculate coating of dust, clenched against the wall with a neglected, rancorous mien, like a large ungainly pet the family had long ago ceased to love. Clearly from outside I could hear those lewd birds doing their wolf-whistles. I began to feel something, a vague, flinching sensation down one side, as if a weak beam of light had been trained on me or a warm breath had brushed my cheek. I glanced quickly towards the doorway, but it was empty. Had there been someone there? Was that a skirl of fading laughter I had caught the end of?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ancient Light»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ancient Light» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ancient Light» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.