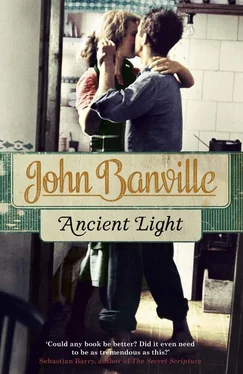

John Banville - Ancient Light

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Banville - Ancient Light» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: Viking Penguin, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ancient Light

- Автор:

- Издательство:Viking Penguin

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-670-92061-7

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ancient Light: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ancient Light»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

gives us a brilliant, profoundly moving new novel about an actor in the twilight of his life and his career: a meditation on love and loss, and on the inscrutable immediacy of the past in our present lives. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tq-oMYIS44o

Ancient Light — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ancient Light», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Then the rattly lift, the vermiform corridors, the crunch of the key in the lock and a stale sigh of air released out of the shadowed room. The muttering porter with his stooped back went ahead and placed the bags just so at the foot of the big square bed that had a hollow in the middle of it and looked as if generations of porters, this one’s predecessors, had been born in it. How accusingly a suitcase once set down can seem to look at one. I could hear Dawn Devonport next door making many mysterious small noises, clinks and knocks and softly suggestive rustlings as she unpacked her bags. Then there came that moment of mild panic when the clothes had been hung, the shoes stowed, the shaving things set out on the bathroom’s marble shelf, where someone’s forgotten cigarette had left a burned stain, a black smear with amber edges. Down in the street a car swished past, and the flare of its head-lamps poked a pencil-ray of yellow light through a chink in the curtains that probed the room from one side to the other before being swiftly withdrawn. Upstairs a lavatory gulped and swallowed, and in response the drain in the bathroom here, getting into the spirit, made a deep-throated sound that might have been a gurgle of lewd laughter.

Downstairs, a humming quiet reigned. I paced on soundless feet over the carpet’s coarse pelt. The restaurant was closed; dimly through the glass I saw the many chairs standing on their tables, as if they had leaped up there in fright of something on the floor. The fellow at the desk mentioned the possibility of room service, though sounding doubtful. Fosco, he was called, so I was told by a tag on his lapel, Ercole Fosco. This name seemed a portent, though I could not say of what. Ercole Fosco. He was the night manager. I liked the look of him. Middle-aged, greying at the temples, heavy-jowled and somewhat sallow in complexion—Albert Einstein in his pre-iconic middle years. His soft brown eyes reminded me a little of Mrs Gray’s. His manner was touched with melancholy, though it was reassuring, too; he reminded me of one of those unmarried uncles who used to appear with gifts at Christmas time when I was a child. I dawdled at the desk, trying to find something to talk to him about, but could think of nothing. He smiled apologetically and made a little fist—what small hands he had—and put it to his mouth and coughed into it, those soft eyes sagging at the outer corners. I could see I was making him nervous, and wondered why. I thought him perhaps not a native of these parts, for he had a northern look—Turin, perhaps, capital of magic, or Milan, or Bergamo, or even somewhere farther off, beyond the Alps. He asked, on a weary note, mechanically, if my room was to my satisfaction. I told him it was. ‘And the signora , she is satisfied?’ I said yes, yes, the signora also was satisfied. We were both very satisfied, very happy. He made a little bow of acknowledgement, bobbing to one side so that it seemed he was not so much bowing as shrugging. I wondered idly if my manner and movements seemed as foreign to him as his seemed to me.

I went and stood inside the front door and looked out through the glass. It was deeply dark out there, in the gap between two street-lights, and the snow appeared almost black, falling rapidly straight down in big wet flakes, in a softly murmurous silence. Perhaps the ferries to Portovenere would not be plying at this time of year, in this weather—that was a subject I could have talked about to Ercole the night manager—perhaps I would have to go by road, back through La Spezia and out by the coast. It was a long way, and on the road there were many twists and bends above ragged cliffs. What a thing it would be for Lydia to hear of, her husband dashed to pieces against rocks on the way to where her daughter had died in similar fashion, in other circumstances.

When I moved, somehow my reflection in the glass did not move with me. Then my eyes adjusted and I saw that it was not my reflection I was seeing, but that there was someone out there, facing me. Where had he appeared from, how had he come to be there? It was as if he had materialised on the instant. He was not wearing an overcoat, and had no hat, or umbrella. I could not quite make out his features. I stood back and pulled the door open for him, it made a sucking sound, and the night bounded in like an animal, agile and eager, with cold air trapped in its fur. The man entered. There was snow on his shoulders, and he stamped his feet on the carpet, first one, then the other, three times each. He gave me a keen, a measuring, look. He was a young man, with a high, domed forehead. Or perhaps, I thought on second glance, perhaps he was not young, for his neatly trimmed beard was grizzled and there were fine wrinkles at the outer corners of his eyes. He wore spectacles with thin frames and oval-shaped lenses, which lent him a vaguely scholarly appearance. We stood there for a moment, facing each other—confronting each other, I was going to say—just as we had a moment ago but with no glass between us now. His expression was one of scepticism tempered with humour. ‘Cold,’ he said, fitting his lips around the word in a wine-taster’s pout. He spoke as if there were some small hindrance in his mouth, a seed or stone, that he must keep manoeuvring his tongue around. Had I already seen him somewhere? I seemed to know him, but how could I?

In the days when I was still working, in the theatre, I mean, for the duration of a run I did not dream. That is, I must have, since we are told the mind cannot be idle, even in sleep, but if I did dream I forgot what I dreamed about. Strutting and prating on stage five nights a week and twice on Saturdays must have fulfilled whatever the function is that dreaming otherwise performs for us. When I retired, though, my nights turned to riot, and more often than not I would wake of a morning in a sweaty tangle, panting and exhausted, having endured long and torturous passages through a chamber of horrors, or a tunnel of love, or sometimes both combined, tumbling helplessly headlong through all manner of grotesque calamities, and with no trousers on, as often as not, my shirttails flapping and my backside on show. Nowadays, ironically, one of my most frequent nightmares—those ungovernable steeds—carries me irresistibly back on stage and dumps me again at the footlights. I am playing in some grand drama or impossibly intricate comedy, and I dry in the middle of a lengthy speech. This did happen to me, famously, in real life, I mean waking life—I was playing Kleist’s Amphitryon—and it brought my theatrical career to an abrupt and inglorious end. It was odd, that lapse, for I had a remarkable memory, in my prime, it may even have been what is called a photographic memory. My method of learning off lines was to fix the text itself, I mean the very pages, as a series of images in my head, to be read and recited from. The terror of this particular dream, though, is that on the pages I have memorised, the text, so black and sharp one moment, the next begins to decay and crumble before my mind’s, my sleeping mind’s, desperately squinting eye. At first I am not greatly worried, convinced that I will be able to recall sufficient portions of the speech to bluff my way through it, or that if worse comes to worst I can improvise the entire thing. However, the audience soon realises that something is going badly awry, while the rest of the actors on stage with me—there is a milling crowd of them—suddenly finding a corpse in their midst, begin to fidget and to throw big-eyed looks at each other. What is to be done? I try to get round the audience, to win it over, by adopting a cravenly ingratiating manner, smiling and lisping, shrugging my shoulders and mopping my brow, frowning at my feet, peering up into the flies, all the while inching sideways towards the blessed shelter of the wings. A horrible comedy attaches to all this, a comedy that is all the more distressing in that it has nothing to do with stage business. Indeed, this is the very essence of the nightmare, that all theatrical pretence has been stripped away, and with it all protection. The scraps of costume that cling to me have become transparent, or as good as, and I am there, bare and exposed, in front of me a packed and increasingly restive house and at my back a cast that would happily kill me if it could and make of me a real corpse. The first catcalls are rising as I start awake, and find myself huddled around myself piteously in the middle of a disordered, hot and sweat-soaked bed.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ancient Light»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ancient Light» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ancient Light» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.