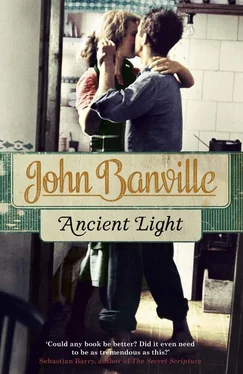

John Banville - Ancient Light

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Banville - Ancient Light» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: Viking Penguin, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ancient Light

- Автор:

- Издательство:Viking Penguin

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-670-92061-7

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ancient Light: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ancient Light»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

gives us a brilliant, profoundly moving new novel about an actor in the twilight of his life and his career: a meditation on love and loss, and on the inscrutable immediacy of the past in our present lives. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tq-oMYIS44o

Ancient Light — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ancient Light», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I did go to confession. The priest I settled on, after much hot-faced agonising in the church’s Saturday-evening gloom, was one I had been to before, many times, a large asthmatic man with stooped shoulders and a doleful air, whose name by happy chance, though perhaps not so happy for him, was Priest, so that he was Father Priest. I worried that he would know me from previous occasions, but the burden I was carrying was such that I felt in need of an ear that I was accustomed to, and that was accustomed to me. Always, when he had slid back the little door behind the grille—I can still hear the abrupt and always startling clack it used to make—he would begin by heaving a heavy sigh of what seemed long-suffering reluctance. This I found reassuring, a token that he was as loath to hear my sins as I was to confess them. I went through the prescribed, singsong list of misdemeanours—lies, bad language, disobedience—before I ventured, my voice sinking to a feathery whisper, on the main, the mortal, matter. The confessional smelt of wax and old varnish and uncleaned serge. Father Priest had listened to my hesitant opening gambit in silence and now let fall another sigh, very mournful-sounding, this time. ‘Impure actions,’ he said. ‘I see. With yourself, or with another, my child?’

‘With another, Father.’

‘A girl, was it, or a boy?’

This gave me pause. Impure actions with a boy—what would they consist of? Still, it allowed of what I considered a cunningly evasive answer. ‘Not a boy, Father, no,’ I said.

Here he fairly pounced. ‘—Your sister?’

My sister , even if I had one? The collar of my shirt had begun to feel chokingly tight. ‘No, Father, not my sister.’

‘Someone else, then. I see. Was it the bare skin you touched, my child?’

‘It was, Father.’

‘On the leg?’

‘Yes, Father.’

‘High up on the leg?’

‘Very high up, Father.’

‘Ahh.’ There was a huge stealthy shifting—I thought of a horse in a horse-box—as he gathered himself close up to the grille. Despite the wooden wall of the confessional that separated us I felt that we were huddled now almost in each other’s arms in whispered and sweaty colloquy. ‘Go on, my child,’ he murmured.

I went on. Who knows what garbled version of the thing I tried to fob him off with, but eventually, after much delicate easing aside of fig leaves, he penetrated to the fact that the person with whom I had committed impure actions was a married woman.

‘Did you put yourself inside her?’ he asked.

‘I did, Father,’ I answered, and heard myself swallow.

To be precise, it was she who had done the putting in, since I was so excited and clumsy, but I judged that a scruple I could pass over.

There followed a lengthy, heavy-breathing silence at the end of which Father Priest cleared his throat and huddled closer still. ‘My son,’ he said warmly, his big head in three-quarters profile filling the dim square of mesh, ‘this is a grave sin, a very grave sin.’

He had much else to say, on the sanctity of the marriage bed, and our bodies being temples of the Holy Ghost, and how each sin of the flesh that we commit drives the nails anew into Our Saviour’s hands and the spear into his side, but I hardly listened, so thoroughly anointed was I with the cool salve of absolution. When I had promised never to do wrong again and the priest had blessed me I went up and knelt before the high altar to say my penance, head bowed and hands clasped, glowing inside with piety and sweet relief—what a thing it was to be young and freshly shriven!—but presently, to my horror, a tiny scarlet devil came and perched on my left shoulder and began to whisper in my ear a lurid and anatomically exact review of what Mrs Gray and I had done together that day on that low bed. How the red eye of the sanctuary lamp glared at me, how shocked and pained seemed the faces of the plaster saints in their niches all about! I was supposed to know that if I were to die at that moment I would go straight to Hell not only for having done such vile deeds but for entertaining such vile recollections of them in these hallowed surroundings, but the little devil’s voice was so insinuating and the things he said so sweet—somehow his account was more detailed and more compelling than any rehearsal I had so far been capable of—that I could not keep myself from attending to him, and in the end I had to break off my prayers and hurry from the place and skulk away in the gathering dusk.

On the following Monday when I came home from school my mother met me in the hall in a state of high agitation. One look at her stark face and her under-lip trembling with anger told me that I was in trouble. Father Priest had called, in person! On a weekday, in the middle of the afternoon, while she was doing the household accounts, there he was, without warning, stooping in the front doorway with his hat in his hand, and there had been no choice but to put him in the back parlour, that even the lodgers were not permitted to enter, and to make tea for him. I knew of course that he had come to talk about me in light of the things I had told him. I was as much scandalised as frightened—what about the much vaunted seal of the confessional?—and tears of outraged injury sprang to my eyes. What, my mother demanded, had I been up to? I shook my head and showed her my innocent palms, while in my mind I saw Mrs Gray, shoeless and her feet bleeding and her hair all shorn, being driven through the streets of the town by a posse of outraged, cudgel-wielding mothers shrieking vengeful abuse.

I was marched into the kitchen, the place where all domestic crises were tackled, and where now it quickly became clear that my mother did not care what it was I had done, and was only angry at me for being the cause of Father Priest’s breaking in upon the tranquillity of a lodgerless afternoon while she was at her sums. My mother had no time for the clergy, and not much, I suspect, for the God they represented either. She was if anything a pagan, without realising it, and all her devotions were directed towards the lesser figures of the pantheon, St Anthony, for instance, restorer of lost objects, and the gentle St Francis, and, most favoured of all, St Catherine of Siena, virgin, diplomatist and exultant stigmatic whose wounds, unaccountably, were invisible to mortal eyes. ‘I couldn’t get rid of him,’ she said indignantly, ‘sitting there at the table slurping his tea and talking about the Christian Brothers.’ At first she had been at a loss and could not grasp his import. He had spoken of the wonderful facilities on offer at the Christian Brothers’ seminaries, the verdant playing fields and Olympic-standard swimming pools, the hearty and nutritious meals that would build strong bones and bulging muscles, not to mention, of course, the matchless wealth of learning that would be dinned into a lad as quick and receptive as he had no doubt a son of hers was bound to be. At last she had understood, and was outraged.

‘A vocation, to the Christian Brothers!’ she said with bitter scorn. ‘—Not even the priesthood!’

So I was safe, my sin undisclosed, and never again would I go for confession to Father Priest, or to anyone else, for that day marked the onset of my apostasy.

___

The material, as Marcy Meriwether called it—making it for some reason sound, to my ear, like the leftovers from a post-mortem—arrived today, by special delivery, all the way from the far sunny side of America. Such a fuss attached to its coming! A clatter of hoofs and a fanfare on the post-horn would not have been out of place. The courier, who bore himself like a Balkan war criminal, with a shaved head and dressed all in shiny black and wearing what looked like commando boots laced halfway up his shins, was not content to ring the bell but immediately set to pounding on the door with his fist. He refused to hand over the big padded envelope to Lydia, insisting that it could only be received by the named recipient, in person. Even when I ventured down from my attic roost, summoned exasperatedly by Lydia, he demanded that I produce photographic identification of myself. I thought this supererogatory at the least, but he was not to be moved—obviously his notion of himself and his duties is crazily deluded—and in the end I fetched my passport, which he pored over for fully half a minute, breathing hard down his nostrils, then for the other half scanned my face with a doubting eye. So cowed was I by his unwarranted truculence that I think my hand shook as I signed my name to the form on his clipboard. I suppose I shall have to get used to this kind of thing, I mean special deliveries and dealing with thugs, if I am going to be a film star.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ancient Light»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ancient Light» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ancient Light» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.