Is it true? Can this be the identity of the ghostly mother and her child who have been haunting me? I want to believe it, but I cannot. I think Lily was lying; I think there is no dead sibling, except in her fancy.

There was a waiting stillness about us now. The air had grown leaden, and the leaves of the tree above us hung inert. A cloud had risen in the sky, blank as a wall, and now there was a hushing sound, and the rain came, hard quick vengeful rods falling straight down and splattering on the pavement like so many flung pennies. In the three hurried steps that it took Lily and me to get to the doorway of the public lavatory we were wet. The door was sealed with a chain and padlock, and we had to cower in the concrete porch, with its green-slimed wall and lingering ammoniac stink. Even here the big drops falling on the lintel above us threw off a chill fine mist that drifted into our faces and made Lily in her thin dress shiver. She wore a black look, huddled there with her head drawn down between her shoulders and her lips set in a line and her thin arms tightly folded. Meanwhile the air was steadily darkening. I remarked the peculiar light, insipid and shrouded, like the light in a dream.

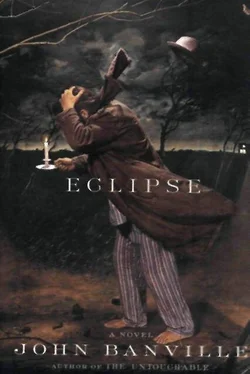

“It’s the eclipse,” Lily said sullenly. “We’re missing it.” The eclipse! Of course. I thought of the thousands standing in silence, in the rain, their faces lifted vainly to the sky, and instead of laughing I felt a sharp and inexplicable pang of sadness, though for what, or whom, I do not know. Presently the downpour ceased and a watery sun, unoccluded, struggled through the clouds, and we ventured out of shelter. The streets that we walked through were awash, grey water with brief pewter bubbles running in the gutters and the pavements shining and giving off wavering flaws of steam. Cars churned past like motorboats, drawing miniature rainbows in their wake, while above us a life-sized one, the daddy of them all, was braced across the sky, looking like a huge and perfect practical joke.

When we came to the square again the circus show was still in progress. We could hear the band inside the tent blaring and squawking, and a big mad voice bellowing incomprehensibly, with awful hilarity, through a loudspeaker. The sun was drying off the canvas of the tent in patches, giving a camouflage effect, and the soaked pennant mounted above the entrance was plastered around its pole. It was not the regular kind of circus tent, what they call the Big Top—I wonder why?—but a tall, long rectangle, suggesting equally a jousting tournament and an agricultural show, with a supporting strut at each of the four corners and a fifth one in the middle of the roof. As we drew near there was a hiatus of some kind in the performance. The music stopped, and the audience inside set up a murmurous buzzing. Some people came out of the tent, ducking awkwardly under the canvas flap in the entrance-way, and stood about in a faintly dazed fashion, blinking in the glistening air. A fat man leading a small boy by the hand paused to stretch, and yawn, and light a cigarette, while the child turned aside and peed against the trunk of a cherry tree. I thought the show was over, but Lily knew better. “It’s only the interval,” she said bitterly, with revived resentment. Just then the red-haired fellow, the one who had grinned at me from the back step of his trailer, appeared from around the side of the tent. Over his red shirt and clown’s trousers he wore a rusty black tailcoat now, and a dented top hat was fixed somehow at an impossible angle to the back of his head. I realised who it was he reminded me of: George Goodfellow, an affable fox, the villain in a cartoon strip in the newspapers long ago, who sported a slender cigarette holder and just such a stovepipe hat, and whose brush protruded cheekily between the split tails of his moth-eaten coat. When he saw us the fellow hesitated, and that knowing smirk crossed his face again. Before I could stop her—and why should I have tried to?—Lily went forward eagerly and spoke to him. He had been about to slip inside the tent, and now stood half turned away from her, holding open the canvas flap and looking down at her over his shoulder with an expression of mock alarm. He listened for a moment, then laughed, and glanced at me, and said something briefly, and then with another glance in my direction slipped nimbly into the darkness of the tent.

“We can go in,” Lily said breathlessly, “for the second half.”

She stood before me in quivering stillness, like a colt waiting to be loosed from the reins, hands clasped at her back and looking intently at the toe of her sandal.

“Who is that fellow?” I said. “What did you say to him?”

She gave herself an impatient shake.

“He’s just one of them,” she said, gesturing toward the caravans and the tethered horses. “He said we could go in.”

The smell inside the tent struck me with a familiar smack: greasepaint, sweat, dust, and, underneath all, a heavy wet warm musky something that was as old as Nero’s Rome. Benches were set out in rows, as in a church, facing a makeshift trestle stage at the far end. There was the unmistakable atmosphere of a matinée, jaded, restless, faintly violent. People were promenading in the aisles, hands in pockets, nodding to their friends and shouting jocular insults. A gang of youths at the back, whooping and whistling, was hurling abuse and apple cores at a rival gang nearby. One of the circus folk, in singlet and tights and espadrilles—it was the Lothario with greasy curls and the nostril stud whom Lily had spoken to in the morning—loitered at the edge of the stage, absent-mindedly picking his nose. I was looking about for Goodfellow when he came bustling in from the left, carrying a piano accordion in one hand and a chair in the other. At sight of him there was a smattering of ironic applause, at which he stopped in his tracks and gave a great start, peering about with exaggerated astonishment, as if an audience were the last thing he had expected. Then he put on a blissful smile of acknowledgement, closing his eyes, and bowed deeply, to a chorus of jeers; his top hat fell off and rolled in a half circle around his feet, and carelessly he snatched it up and clapped it on again, and proceeded gaily toward the front of the stage, the accordion hanging down at his side with the bellows at full stretch and emitting tortured squeaks and wheezes. At every other step he would pause, pretending not to know where these cat-call sounds were coming from, and would peer over his shoulder, or glare suspiciously at the people in the front row, and once even twisted himself into a corkscrew shape to stare down in stern admonishment past his shoulder at his own behind. When the laughter had subsided, and after essaying a few experimental runs on the keyboard, head inclined and gaze turned soulfully inward, like a virtuoso testing the tone of his Stradivarius, he threw himself back on the chair with a violent movement of the shoulders and began to play and sing raucously. He sang in a reedy falsetto, with many sobs and gasps and cracked notes, swaying from side to side on the chair and passionately casting up his eyes, so that a rim of yellowish white was visible below the pupils. After a handful of rackety numbers—“O Sole Mio” was one, and “South of the Border”—he ended with a broad flourish by letting the accordion fall open flabbily across his knees, producing from it a wounded roar, and immediately slammed it shut again. After that for a long moment he sat motionless, with the instrument shut in his lap, stricken-faced, staring before him with bulging eyes, then rose, wincing, and scuttled off at a knock-kneed run, a hand clutched to his crotch.

Lily thought all this was wonderful, and laughed and laughed, leaning her head weakly against my shoulder. We were seated near the front, where the crowd was densest. The atmosphere under the soaked canvas was heavy and humid; it was like being trapped inside a blown-up balloon, and my head had begun to ache. Until it started up I did not notice the band, down at the side of the stage, a three-piece ensemble of trumpet, drums, and an amplified keyboard on a sort of stand. The trumpet, unexpectedly, was played by a large and no longer young woman, heavily made up and wearing a blonde wig, who on the high notes would go into a crouch and screw shut her eyes, as if she could not bear the intensity of the brassy music she was making. The drummer, a bored young man with sideburns and an oiled quiff, smoked a cigarette with negligent ease all the while that he was playing, shifting it expertly from one corner of his mouth to the other and letting the smoke dribble out at his nostrils. The player at the keyboard was old, and wore braces; a wispy fan of hair was combed flat across the bald dome of his skull. Preceded by a rattle on the kettledrum, Goodfellow reappeared, bounding into the middle of the stage, kissing bunched fingers at us and opening wide his arms in a gesture of swooning gratitude, as if it were wild applause that was being showered on him, instead of howls and lip-farts. Then the band went into an oily, drunken tango and he began to dance, sashaying and slithering about the stage on legs that might have been made of rubber, his arms wrapped about himself in a lascivious embrace. Each time he passed her by the trumpet player blew a loud, discordant squeal and thrust the bell of her instrument lewdly in the direction of his skinny loins. He pretended to ignore her, and pranced on, with a disdainful waggle of his backside. At the close he did a pirouette, twisting himself into that corkscrew shape again, coat-tails flying and his arms lifted and fingers daintily touching high above his head, then leapt into the air and executed a scissors-kick, and finished in the splits, landing with a thump loud enough to be heard over the music and bringing delighted shrieks of mock agony from the laughing youths at the back. His top hat had stayed in place throughout, and now he skipped nimbly to his feet and snatched it off and made another low bow, the hat pressed to his breast and an arm upswept behind him with rigid index finger pointing aloft. Lily, laughing, said into my ear in a whispered wail that she was sure she was going to wet herself.

Читать дальше