Finally I got an old ice-cream carton out of the cupboard and filled it up with water. I dunked the mouse in and held it down with a wooden spoon. It looked up at me, amazed, as it struggled to breathe. Three tiny air bubbles escaped, one after the other.

I write Zoey’s baby a text: HIDE!

‘Who’s that to?’

‘No one.’

She leans over the table. ‘Let me see.’

I delete it, show her the blank screen.

‘Was it to Adam?’

‘No.’

She rolls her eyes. ‘You practically have sex in the garden and then you get some kind of perverted kick out of pretending it didn’t happen.’

‘He’s not interested.’

She frowns. ‘Of course he’s interested. His mum came out and caught you, that’s all. He’d happily have shagged you otherwise.’

‘It was four days ago, Zoey. If he was interested, he’d have contacted me.’

She shrugs. ‘Maybe he’s busy.’

We sit with that lie for a minute. My bones poke through my skin, I’ve got purple blotches under my eyes, and I’m definitely beginning to smell weird. Adam’s probably still washing his mouth out.

‘Love’s bad for you anyway,’ Zoey says. ‘I’m living proof of that.’ She chucks her magazine down on the table and looks at her watch. ‘What the hell am I paying for exactly?’

I move seats to be next to her.

‘Maybe it’s a joke,’ she says. ‘Maybe they take your money, let you sweat, and hope you get so embarrassed that you just go home.’

I take her hand and hold it between mine. She looks a bit surprised, but doesn’t take hers away.

The windows have darkened glass in them so that you can’t see the street. When we arrived, it was beginning to snow; people doing their Christmas shopping were all wrapped up against the cold. In here, heat is blasting from the radiators and piped music washes over us. The world out there could’ve ended, but in here you wouldn’t know it.

Zoey says, ‘When this is over and it’s just you and me again, we’ll get back to your list. We’ll do number six. Fame, isn’t it? I saw this woman on the telly the other day. She’s got terminal cancer and she’s just done a triathlon. You should do that.’

‘She’s got breast cancer.’

‘So?’

‘So it’s different.’

‘Running and cycling keep her motivated. How different can it be? She’s lived much longer than anyone thought she would, and she’s really famous.’

‘I hate running!’

Zoey shakes her head at me very solemnly, as if I’m being deliberately difficult. ‘What about Big Brother ? They’ve never had anyone like you on that before.’

‘It doesn’t start until next summer.’

‘So?’

‘So think about it!’

And that’s when the nurse comes out of a side room and walks towards us. ‘Zoey Walker? We’re ready for you now.’

Zoey hauls me up. ‘Can my friend come?’

‘I’m sorry, but it’s better if she waits outside. It’s just a discussion today, but it’s not the type of discussion that’s easy to have in front of a friend.’

The nurse sounds very certain of this and Zoey doesn’t seem able to resist. She passes me her coat, says, ‘Look after this for me,’ and goes off with the nurse. The door shuts behind them.

I feel very solid. Not small, but large and beating and alive. It’s so tangible, being and not being. I’m here. Soon I won’t be. Zoey’s baby is here. Its pulse tick-ticking. Soon it won’t be. And when Zoey comes out of that room, having signed on the dotted line, she’ll be different. She’ll understand what I already know – that death surrounds us all.

And it tastes like metal between your teeth.

‘Where are we going?’

Dad takes one hand off the steering wheel to pat me on the knee. ‘All in good time.’

‘Is it going to be embarrassing?’

‘I hope not.’

‘Are we going to meet someone famous?’

He looks alarmed for a moment. ‘Is that what you meant?’

‘Not really.’

We drive through town and he won’t tell me. We drive past the housing estates and onto the ring road, and my guesses get completely random. I like making him laugh. He doesn’t do it much.

‘Moon landing?’

‘No.’

‘Talent competition?’

‘With your singing voice?’

I phone Zoey and see if she wants to have a guess, but she’s still freaking out about the operation. ‘I have to take a responsible adult with me. Who the hell am I going to ask?’

‘I’ll come.’

‘They mean a proper adult. You know, like a parent.’

‘They can’t make you tell your parents.’

‘I hate this,’ she says. ‘I thought they’d give me a pill and it would just fall out. Why do I need an operation? It’s only the size of a dot.’

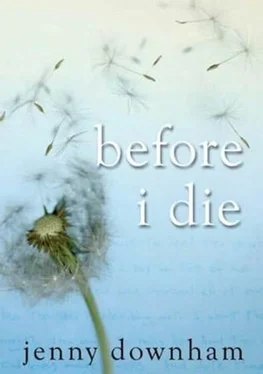

She’s wrong about that. Last night I got out the Reader’s Digest Book of Family Medicine and looked up pregnancy. I wanted to know how big babies are in week sixteen. I discovered they’re the length of a dandelion. I couldn’t stop reading. I looked up beestings and hives. Lovely mundane, family illnesses – eczema, tonsillitis, croup.

‘You still there?’ she says.

‘Yeah.’

‘Well, I’m going now. Acid liquid is coming up my throat and into my mouth.’

It’s indigestion. She needs to massage her colon and drink some milk. It will pass. Whatever she decides to do about the baby, all Zoey’s symptoms will pass. I don’t tell her this though. Instead, I press the red button on my phone and concentrate on the road ahead.

‘She’s a very silly girl,’ Dad says. ‘The longer she leaves it, the worse it will be. Terminating a pregnancy isn’t like taking out the rubbish.’

‘She knows that, Dad. Anyway, it’s nothing to do with you – she’s not your daughter.’

‘No,’ he agrees. ‘She’s not.’

I write Adam a text. I write, WHERE THE HELL ARE U? Then I delete it.

Six nights ago his mum stood on the doorstep and cried. She said the fireworks were terrifying. She asked why he’d left her when the world was ending.

‘Give me your mobile number,’ he told me. ‘I’ll call you.’

We swapped numbers. It was erotic. I thought it was a promise.

‘Fame,’ Dad says. ‘Now, what do we mean by fame, eh?’

I mean Shakespeare. That silhouette of him with his perky beard, quill in hand, was on the front of all the copies of his plays at school. He invented tons of new words and everyone knows who he is after hundreds of years. He lived before cars and planes, guns and bombs and pollution. Before pens. Queen Elizabeth I was on the throne when he was writing. She was famous too, not just for being Henry VIII’s daughter, but for potatoes and the Armada and tobacco and for being so clever.

Then there’s Marilyn. Elvis. Even modern icons like Madonna will be remembered. Take That are touring again and sold out in milliseconds. Their eyes are etched with age and Robbie isn’t even singing, but still people want a piece of them. Fame like that is what I mean. I’d like the whole world to stop what it’s doing and personally come and say goodbye to me when I die. What else is there?

‘What do you mean by fame, Dad?’

After a minute’s thought he says, ‘Leaving something of yourself behind, I guess.’

I think of Zoey and her baby. Growing. Growing.

‘OK,’ Dad says. ‘Here we are.’

I’m not sure where ‘here’ is. It looks like a library, one of those square, functional buildings with lots of windows and its own car park with allocated spaces for the director. We pull into a disabled bay.

The woman who answers the intercom wants to know who we’ve come to see. Dad tries to whisper, but she can’t hear, so he has to say it again, louder. ‘Richard Green,’ he says, and he gives me a sideways glance.

Читать дальше