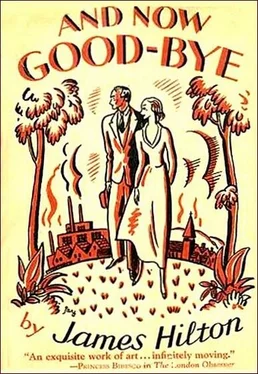

James Hilton

And Now Good-bye

The Redford rail smash was a bad business. On that cold November morning, glittering with sunshine and a thin layer of snow on the fields, the London- Manchester express hit a wagon that had strayed on to the main line from a siding. Engine and two first coaches were derailed; scattered cinders set fire to the wreckage; and fourteen persons in the first coach lost their lives. Some, unfortunately, were not killed outright. A curious thing was that even when all the names of persons who could possibly have been travelling on that particular train on that particular morning, had been collected and investigated, there were still two charred bodies completely unaccounted for, and both of women.

Behind the second coach the force of the collision was not felt so disastrously; there were several casualties in the third, but in the fourth, which was a restaurant-car, occupants escaped with a shaking.

As usual on such occasions there were heroic incidents. Conspicuous among these was the behaviour of one of the restaurant-car passengers, a middle-aged man, who jumped down to the track within a few seconds of the impact, and began work of rescue amidst the piled up and already burning debris. Five persons, it was afterwards computed, owed their lives to his gallantry, nor could he be persuaded to desist until his arms and hands were badly burned, and all hope of saving further lives had clearly to be abandoned. Passengers and railway officials alike were limitless in his praise—“He was like a fury,” one said, “dashing into the flames again and again, just as if they weren’t there—it seemed impossible that one man could do so much in so short a time.”

The following day was Sunday and Armistice Day, and the newspapers were naturally full of stories of the disaster and of its hero. He had collapsed, it was reported, after his efforts, but letters and papers in his possession revealed him to be the Reverend Howat Freemantle, a dissenting minister in Browdley, Lancashire. Interest in him was further stirred by the disclosure, made by his wife, who was telegraphed for and arrived later in the day, that he had been travelling alone. This seemed to set his heroism on a higher pinnacle than ever; Mr. James Douglas made it the theme of a long and moving article; and a chorus of adulation rose from all parts of the country. For, as one ‘leader’ put it: “Many doubtless would have done as much for their loved ones, but this man’s devotion and self-sacrifice were for complete strangers, and in this he showed himself magnificently worthy of his profession. In these days, when so much is heard of the failure of organised religion to attract the masses, the selfless bravery of this Nonconformist clergyman strikes a note that will echo far beyond the thunder of rival sectaries.”

The Reverend Howat Freemantle spent a week in hospital, and for a few days there were fears that he might have to lose one of his hands. Meanwhile the gaze of the whole country was on him, for the Press, with that capriciously epidemic enthusiasm that partly leads and partly follows the mood of its registered readers, decided unanimously that he was the ‘big news’ of the moment. Photographs of him, looking tired and rather sad in his hospital bed, appeared on front pages; his face was impressive and thoughtful, and it was even commented by some that he had ‘the eyes of a saint’. Of the disaster and of his own exploits he would say not a word—a pathetically understandable attitude in a man in whom modesty and horror were doubtless equally profound. When at last the announcement was made that his hand might, after all, be saved, and that he would soon be fit to undertake the journey to Browdley, the sentimental heart of the newspaper-reading public gave a great upward leap.

That journey home was rather like the return of a wounded victor after a successful military campaign. Hundreds cheered him as he walked from the ambulance to the train at Redford; and by courtesy of the railway company his coach was sent on a through line to Browdley Station, where he was welcomed by the Mayor and Corporation, the Salvation Army Silver Prize Band, and a crowd estimated at nearly five thousand. It had not been realised, however, that he was so ill; and as he was helped down the station slope by his wife and sister- in-law, the Mayor hurriedly cancelled a prepared speech and substituted a few short sentences of praise and welcome. Even the cheers of the crowd were hushed by the man’s tragic appearance, and his words, “Thank you all—very much,” were clearly heard amidst an awestricken silence. But the cheers swelled out again as the ambulance passed through the narrow streets to the Manse.

The massed limelights of the Press then focused themselves upon that middle-sized manufacturing town, of which few persons in other parts of the country had ever even heard; and it was soon discovered that in the Reverend Howat Freemantle Browdley had possessed no ordinary minister. Everywhere citizens and chapel-goers testified to his generosity, his kindliness, and his devotion to good works, while it was recalled that during the War he had served in Gallipoli as an ordinary soldier and been wounded twice. Nor in Browdley had he confined himself to strictly professional work; his sermons had been eloquent, but he had also identified himself with local literary and artistic societies, the League of Nations Union, and other movements. Newspaper interviewers, unable to approach the man himself (he was confined to his room and could see nobody), found his wife and sister-in-law most gratifyingly ready to answer questions; among other matters it was revealed that his stipend was a very poor one, and that, like so many other clergymen in industrial districts, he had for some time been hard put to it to make ends meet. In particular, he could barely afford even the most urgent repairs to the large, red-bricked residence with which an earlier and more prosperous generation had burdened him. Such facts, together with an insurgent wave of popular emotion, prompted a leading daily newspaper to open a fund for the provision of ‘some tangible expression of nation-wide esteem’. Headed by a contribution of fifty guineas from the proprietor, Sir William Folgate, it speedily reached a sum of nearly eleven hundred pounds, a cheque for which was eventually handed to Freemantle at a special meeting convened in Browdley Town Hall. He was still suffering then from the effects of a complete nervous and mental breakdown, and could not make more than a very short speech of thanks. The money, he said, would be devoted entirely to local charities.

But this was by no means the only tribute paid to his heroism. A certain Miss Monks, aged eighty-nine, who belonged to Freemantle’s chapel, was so deeply overcome by reading newspaper accounts of how the minister had behaved that she died of heart failure; whilst another old lady, who lived at Cheltenham, and had never even seen Freemantle, offered to pay for the education of his children. He had none, as it happened, of school age, so that the lady’s beneficence was frustrated; but he was able to accept Sir William Folgate’s three months’ loan of a luxurious villa overlooking the sea at Bournemouth. It should perhaps be added that he received many anonymous gifts, among them being an Austin Seven car, which had to be sold, since neither he nor any of his family could drive.

One of the many disclosures made by Mrs. Freemantle to an interviewer had been that her husband’s hobby was the composition of music. The enterprising journalist had wished to know more of this, so she had hunted up as many of her husband’s compositions as she could find and handed them over. Among them was one, dated 1909, which for some reason attracted more attention than the rest, and within a few days Mrs. Freemantle received an offer from a firm of publishers. But she was unwise enough to hold out for too high terms and negotiations finally broke down, with the unfortunate result that none of Freemantle’s music has yet been made accessible to the general public.

Читать дальше