The youth answered angrily, "The demonstration today was peaceful. The authorities had given permission for it. Top men from all walks of life participated in it. At first it proceeded safely, until the middle section reached Ezbekiya Garden. Before we knew what was happening, bullets fell upon us from behind the wall, for no reason at all. No one had confronted the soldiers in any manner. We had even forbidden any chants in English to avoid provoking them. The soldiers were suddenly stricken by an insane impulse to kill. They got their rifles and opened fire. Everyone has agreed to send a strong protest to the British Residency. It’s even been said that Allenby will announce his regrets for what the soldiers did".

In the same sick tone, the proprietor complained, "But he will not bring the dead back to life".

"Alas, no".

Al-Sayyid Ahmad, racked by distress, said, "He’s never participated in any of the violent demonstrations. This was the first demonstration he took part in".

The young men looked knowingly at each other but did not utter a word. Al-Sayyid Ahmad seemed to be growing impatient with the way they were separating him from Fahmy and the rest of the world. He moaned and said, "The matter’s in God’s hands. Where can I find him now?"

The young man answered, "In the Qasr al-Ayni Hospital". When he saw that the proprietor was in a hurry to leave, he gestured for him to wait. "There will be a funeral procession for him and thirteen of his fellow martyrs at exactly three o'clock tomorrow afternoon".

The father cried out in distress, "Won't you allow me to begin his funeral procession at his home?"

The young man said forcefully, "No, his funeral will be with his brothers in a public ceremony". Then he entreated the man, "Qasr al-Ayni is cordoned off by the police. It would be better to wait. We intend to allow the families of the martyrs to pay their last respects to them in private before the funeral procession. It would not be right for Fahmy to have an ordinary funeral like a person who dies at home". In parting he held his hand out to the bereaved father and said, "Endure patiently. Endurance is from God".

The others shook hands with al-Sayyid Ahmad, repeating their condolences. Then they all departed. He leaned his head on his hand and closed his eyes. He heard the voice of Jamil al-Hamzawi offering his condolences in a sobbing voice, but he seemed distressed by kind words. He could not bear to stay there. He left his seat and moved slowly out of the store, walking with heavy steps. He had to get over his bewilderment. He did not even know how to feel sad. He wanted to be all alone, but where? The house would turn into an inferno in a minute or two. His friends would rally round him, leaving him no opportunity to think. When would he ponder the loss he had undergone? When would he have a chance to get away from everyone? That seemed a long way off, but it would no doubt come. It was the most consolation he could hope for at present. Yes, a time would come when he would be all alone and could devote himself to his sorrow with all his soul. Then he would scrutinize Fahmy’s life in light of the past, present, and future, all the stages from childhood to the prime of his youth, the hopes he had aroused and the memories he had left behind, giving free rein to tears so he could totally exhaust them. Truly he had before him ample time that no one would begrudge him. There was no reason to be concerned about that. Consider the memory of the quarrel they had had after the Friday prayer at al-Husayn or that of their conversation that morning, when Fahmy had appealed for his affection and he had reprimanded him-how much of his time would they require as he reflected, remembered, and grieved? How much of his heart would they consume? How many tears would they stir up? How could he be distressed when the future held such consolations for him? He raised his head, which was clouded by thought, and saw the blurred outline of the latticed balconies of his home. He remembered Amina for the first time and his feet almost failed him. What could he say to her? How would she take the news? She was weak and delicate. She wept at the death of a sparrow. "Do you recall how her tears flowed when the son of al-Fuli, the milkman, was killed? What will she do now that Fahmy’s been killed… Fahmy killed? Is this really the end of your son? O dear, unhappy son!.. Amina… our son was killed. Fahmy was killed… What?… Will you forbid them to wail just as you previously forbade them to trill with joy? Will you wail yourself or hire professional mourners? She’s probably now at the coffee hour with Yasin and Kamal, wondering what has kept Fahmy. How cruel! I'll see him at Qasr al-Ayni Hospital, but she won't. I won't allow it. Out of cruelty or compassion? What’s the use, anyway?"

He found himself in front of the door and stretched his hand toward the knocker. Then he remembered the key in his pocket. He took it out and opened the door. When he entered, he heard Kamal’s voice singing melodiously:

Visit me once each year,

For it’s wrong to abandon people forever.

THE END

I want to thank Mary Ann Carroll for being the first reader, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis for her sensitive editing, Riyad N. Dels had for assistance with some obscure vocabulary and expressions, and Sarah and Franya Hutchins for their patience. Although others have contributed to this translation, I am happy to bear responsibility for it.

William Maynard Hutchins

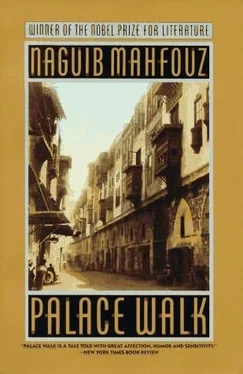

Naguib Mahfouz was born in Cairo in 1911 and began writing when he was seventeen. A student of philosophy and an avid reader, he has been influenced by many Western writers, including Flaubert, Balzac, Zola, Camus, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and, above all, Proust. He has more than thirty novels to his credit, ranging from his earliest historical romances to his most recent experimental novels. In 1988, Mr. Mahfouz was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. He lives in the Cairo suburb of Agouza with his wife and two daughters.

al-Sayyid Ahmad Abd al-Jawad — father and family patriarch (45), shop owner

Aisha — daughter, 16; blond beauty, but useless

Amina — wife and mother of four plus one stepson

Fahmy — son, tall and slim

Kamal — youngest son, 9, prankster

Khadija — daughter, 20, second eldest, strong and plump, brunette

Yasin — oldest son, 21, stocky-large like father, Amina’s stepson

Haniya — Yasin’s mother

Umm Hanafi — family servant

al-Sayyid Muhammad Ridwan — their next-door neighbor

Bahija Ridwan — Maryam’s mother

Hasan Ibrahim — police officer interested in marrying Aisha

Jalila — performer al-Sayyid had loved for such a long time

Jaljal — Zubayda’s servant

Jamil al-Hamzawi — father’s shop assistant

Madam Nafusa — the widow of al-Hajj Ali al-Dasuqi, owns seven stores

Maryam — next-door neighbor’s daughter; Ridwan. Fahmy wishes to marry her

Mrs. Shawkat — the oldest friend of the parents

Sadiqa — Amina’s mother’s servant

Shaykh Mutawalli Abd al-Samad — blind religious guide and friend

Umm Ali — matchmaker

Zanuba — Zubayda’s foster daughter

Zubayda — a nightclub singer

A book about the center of a universe. A look inside a family from a different society. The place of people in the world and the individuals in that family. Written in the words of a great poet. A true understanding of people and one’s self.

Critical acclaim for "Palace Walk":

'lt is Mahfouz’s wonderful ability to delineate human beings from their outer appearances which gives "Palace Walk" its universal appeal. I shall read it again and again'

Читать дальше