“A Murky Fate,” meanwhile, gives us an aging, unmarried, and childless woman who invites into her overcrowded apartment a fat, balding, married coworker for a few undignified moments of sex. Why? The next day, she inspects her feelings and discovers that she cannot live without him, and this discovery, instead of breaking her heart—instead of condemning her to the pain and humiliation of unrequited love—makes her weep with happiness. At first we feel a mix of disdain and exasperation for the pathetic heroine, but by the end we are weeping with her, for her. She believes she has found a semblance of love. Who are we to deny her?

* * *

Petrushevskaya worked as a journalist in radio, television, and trade magazines, but it was as a playwright that she first made her name. Theater companies embraced her dramas, which expressed her miraculous ear for the registers of colloquial speech, from the self-serious, educated speech of the intelligentsia to the hilarity of sputtering alcoholics. As in her plays, so in her stories: Petrushevskaya listened on crowded subway platforms, on playgrounds, in apartments, and in other locales of ordinary life. All the stories in this collection have happened. All these sad and strange characters have real counterparts.

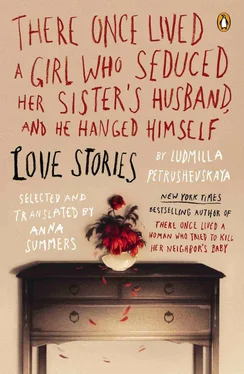

And so Petrushevskaya’s stories had to be suppressed; editors distrusted her pessimism, while official critics accused her of blackening reality. It was not until 1988, when she was fifty, that her first book of prose was permitted to circulate. Her stories contained no scenes of bloody repression, no labor camps, no knocks on the door in the black night—no politics at all. What appeared to be domestic stories of fringe characters, however, conveyed a verdict as brutal as the most overt dissident fiction. In place of the heroic new men and new women, Petrushevskaya offered a cast of pathetic characters barely holding themselves together. Her continual flow of insight into the emotional psychology of late – and post-Soviet society, her collective portrait of imperiled humanity that’s always been the highest object of communist idealism, must have terrified cultural bureaucrats in charge of official reality. For in her love stories, the revolution, having begun with the promise of communal apartments, degenerated and died in those same apartments. The juxtaposition of the fate of her characters and their high expectations for love and respect was unforgiving—and unforgivable.

I grew up in one of the concrete apartment buildings that have surrounded Moscow since the seventies, in the care of a mother who adored Petrushevskaya’s fatalism as lived reality and taught me to read her in the same spirit. When her stories first circulated, the shock of recognition was terrible indeed among my parents’ generation. Petrushevskaya, it turned out, had been writing about their lives; it was their claustrophobic apartments that she described, their ungrateful children, their sick parents, their frustrated marriages.

In college during the hopeful nineties I returned to reading her, and what struck me then was the atypicality of her stories. In Russia’s culture the kind of stories shared with strangers on crowded buses and subways are extreme, the stuff of urban legends, myths, and folklore. Later still, when I became a wife and mother, I learned to read her with a smile, to delight in her humor, her irony, her steadfast refusal to save her characters, or her readers, from themselves.

Petrushevskaya waited for many years to see her first book into print, and in spite of official suppression, she never stopped writing. She couldn’t have kept her talent and her spirit alive on the diet of self-pity. No, even her gloomiest stories whisper their moments of humor, irony, and, yes, redemption to those readers willing to listen. She wants us to be strong, and clever, and resourceful, like the Russian people she loves.

ANNA SUMMERS

This is what happened. An unmarried woman in her thirties implored her mother to leave their studio apartment for one night so she could bring home a lover.

This so-called lover bounced between two households, his mother’s and his wife’s, and he had an overripe daughter of fourteen to consider as well. About his work at the laboratory he constantly fretted but would brag to anyone who listened about the imminent promotion that never materialized. The insatiable appetite he displayed at office parties, where he stuffed himself, was the result of an undiagnosed diabetes that enslaved him to thirst and hunger and lacquered him with pasty skin, thick glasses, and dandruff. A fat, balding man-child of forty-two with a dead-end job and ruined health—this was the treasure our unmarried thirtysomething brought to her apartment for a night of love.

He approached the upcoming tryst matter-of-factly, almost like a business meeting, while she approached it from the black desperation of loneliness. She gave it the appearance of love or at least infatuation: reproaches and tears, pleadings to tell her that he loved her, to which he replied, “Yes, yes, I quite agree.” But despite her illusions she knew there was no romance in how they moved from the office to her apartment, picking up cake and wine at his request; how her hands shook when she was unlocking the door, terrified that her mother might have decided to stay.

The woman put water on for tea, poured wine, and cut cake. Her lover, stuffed with cake, flopped himself across the armchair. He checked the time, then unfastened his watch and placed it on a chair. His underwear and body were surprisingly white and clean. He sat down on the edge of the sofa, wiped his feet with his socks, and lay down on the fresh sheets. He did his business; they chatted. He asked again what she thought of his chances for a promotion and got up to leave. At the door, he turned back toward the cake and cut himself another large piece, then licked the knife. He asked her to change a three-ruble bill but, receiving no reply, pecked her on the forehead and slammed the door behind him. She didn’t get up. Of course the affair was over for him. He wasn’t coming back—in his childishness he hadn’t understood even that much, skipping off happily, unaware of the catastrophe, taking his three rubles and his overstuffed belly.

The next day she didn’t go to the cafeteria but ate lunch at her desk. She thought about the coming evening, when she’d have to face her mother and resume her old life. Suddenly she blurted out to her officemate: “Well, have you found a man yet?” The woman blushed miserably: “No, not yet.” Her husband had left her, and she’d been living alone with her shame and humiliation, never inviting any of her friends to her empty apartment. “How about you?” she asked. “Yes, I’m seeing someone,” the woman replied. Tears of joy welled up in her eyes.

But she knew she was lost. From now on, she understood, she’d be chained to the pay phone, ringing her beloved at his mother’s, or his wife’s. To them she’d be known as that woman —the last in a series of female voices who had called the same numbers, looking for the same thing. She supposed he must have been loved by many women, all of whom he must have asked about his chances for promotion, then dumped. Her beloved was insensitive and crude—everything was clear in his case. There was nothing but pain in store for her, yet she cried with happiness and couldn’t stop.

That summer we watched a transformation by the sea. We were staying across the street from a resort for workers; she was one of the guests. We couldn’t ignore her—she was too vulgar. We overheard her laughter on the beach, at the local wine seller, on the way to the market—everywhere. Just imagine her: a tight perm, plucked eyebrows, gaudy lipstick, a miniskirt, new platforms. It was all cheap and tasteless but with an attempt at fashion. She strained, pathetically, from her curls to her heels, and for what? To look no worse than the others, not to miss her chance—her last one, perhaps—for a little womanly happiness (as imagined in soap operas). A blue-collar Carmen, searching for some seaside romance.

Читать дальше