“Oooh,” she said, tearing open the package and carefully opening the box.

As the silver and gold shone in her eyes, everyone stopped talking and held their breath. Rachel slowly picked up the ring and turned it in her fingers.

“It’s beautiful, James,” she said quietly. “And I’m so honored, really I am. It’s such a wonderful thing to do. But… really… I’m sorry… there’s absolutely no way I can marry you.”

James groaned. “I was afraid this might happen,” he said. “It’s just a ring, Rachel, I didn’t mean—”

He stopped midsentence because everyone was laughing at him, Rachel the hardest of all.

“I know, James!” she said. “I’m joking! Georgie told me about your little panic attack!”

James groaned again and slapped his forehead, which brought some of the color running back to his face.

“But the ring really is beautiful,” Rachel told him. “Thank you. I’ll treasure it always.”

“My pleasure—I think.”

James grinned as he leaned across the floor mat to give her a kiss.

“Hey,” he said as he moved back to his place, “what do you mean you wouldn’t marry me?”

Rachel giggled. “Look at you! You’re a mess, darling, a big scruffy—and most of the time drunken—mess. How could I ever take you home to meet my parents?”

“Now hang on—”

“And besides, your surname is Allcock!”

“That’s a very noble old English name, I think you’ll find.”

“That may be so, James, but I can’t go through the rest of my life being known as Mrs. Allcock!”

And everyone burst out laughing, apart from James, who looked disappointed, and me, because I thought Rachel would make a lovely Mrs. Allcock. Judging by the small shadows now crossing James’s face, I think he did too.

24

24

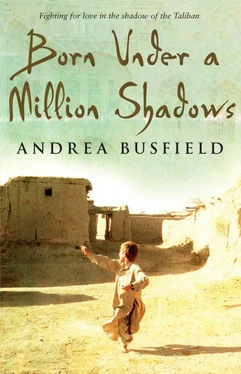

AS WE WOUND our way around the gray mountains down to the blue of Surobi and into the flatness of green that took us to Jalalabad, it struck me that this was a journey that usually followed some kind of disaster in my life—first it was James’s knife in the Frenchman’s ass, and now it was Spandi’s death—and I couldn’t help wondering what catastrophe might pour soil on my head if I ever came this way again. Would my mother have died? Would Jamilla have been sold for a night of hashish? Would I have woken up one day to find a rat running around Kabul with my nose in its stomach?

The more I thought about it, the more it spoiled the journey, to be honest. I was also sweating in the backseat like a fat man wrapped in a patu because the air-conditioning was broken. Even though Jalalabad was only a few hours away from Kabul, the sun was about one hundred times stronger, and the heat of it filled my mouth in the closed space of the Land Cruiser that had come to pick us up before lunch.

Georgie did little to make the journey any more fun as she sat in the front seat talking to her office most of the time, because the mobile phone reception kept disappearing halfway through her conversations.

“Are you hungry?” she asked me eventually, snapping her phone shut as we came to a stop in front of the Durunta tunnel. Two giant trucks were trapped inside facing each other, unable to pass and unable to go backward because of all the other cars, taxis, and Land Cruisers that had arrived to block them in.

“I’m starving actually,” I replied.

That morning I’d eaten only a little bread and honey because eggs were now off the menu thanks to a report my mother had heard on the news. Apparently we were all about to die from bird flu, so anything that had anything to do with chickens was now officially banned from the house.

“Good, let’s get out then,” Georgie said.

We left the car with the driver because we knew it wouldn’t be going anywhere fast and jumped into the chaos of the street. Around us, the air was thick with bad-tempered shouting and angry car horns as a group of policemen tried to sort out the mess. As usual, everyone was pretty much ignoring them, even getting out of their vehicles to bark their own orders, while other cars tried to overtake and squeeze past one another, hoping somehow to force their way into the tunnel.

I imagined that if I was a bird looking down from the sky, the road might look like it was covered by a giant blanket of metal.

Weaving our way past rattling engines, we reached one of the fish restaurants lining the road. Outside, a man stood in front of a metal bowl that was spitting oil. He waved us inside, away from the smell of burning fat and heavy car fumes.

We walked past him, through a small room where a group of men sat on the floor tearing apart bits of fish with their bread or picking bones as thin as needles from their mouths. We nodded at them, they nodded back, and we walked out through a door at the back of the restaurant.

In front of us, Durunta’s blue-green lake shone its colors before a jagged line of brown mountains. It was incredibly beautiful. And it would have been incredibly peaceful too if the air hadn’t been filled with the sound of men insulting one another’s mothers.

A small, thin man with a small, thin mustache and no beard waved us into another small room balanced on the edge of the lake. Inside there was a massive window, and the man got to work with a cloth, shooing away a cloud of flies that buzzed around in circles before landing back in their original positions.

We sat down on bright red cushions dotted with greasy fingerprints, and Georgie ordered two cans of Pepsi, a plate of naan bread, and some fish.

I looked out of the window that didn’t have any glass in it and saw a tiny boat covered in pretty colored ribbons playing out on the water. Below us I also saw a small boy, about my age, scrambling up the hill from the lake. The top half of his body was naked, and his trouser bottoms, patchy with wet, had been rolled up.

“Well, at least the food is fresh,” Georgie commented, because the boy was holding a plastic bowl filled with flapping bony lake fish.

“Yes, that’s one thing,” I agreed, falling back onto the dirty cushions. “So, why do you need to see Baba Gul again?”

“I need to finalize some details,” Georgie replied. “The organization I work for just received a load of money, and we’ve got a great opportunity to really move this cashmere project forward.”

“In what way?”

“Well, we’ve been trying to get businesspeople to invest, and an Italian company has shown an interest in buying into a factory here. That would bring a lot of jobs, Fawad. It would also create a demand for cashmere, giving hundreds of thousands of farmers an extra source of income. I want Baba Gul and his family to be a part of that. Besides, I thought it would give you a chance to say hi to your girlfriend.”

“She’s not my girlfriend!” I protested, hitting Georgie with a fly swatter that had been left on the floor.

“But you know who I’m talking about, don’t you?”

“Oh, shut up, Georgie!”

“Oh, shut up, Fawad!”

Smiling, we both began to pick at the bony fish that had arrived on paper plates. And as I ate I thought of Mulallah running through the fields with her red scarf streaming from her neck like the tail of a firework, and I wondered whether Georgie was right and whether Mulallah would become my girlfriend.

After lunch we didn’t stop at Haji Khan’s house; we kept on driving right through Jalalabad, beeping nonstop at the people, cars, and tuk-tuks racing like ants around the yellow streets, on past the picture of Haji Abdul Qadir and into the tunnel of trees until we came to the turn that took us to Shinwar.

Читать дальше

24

24