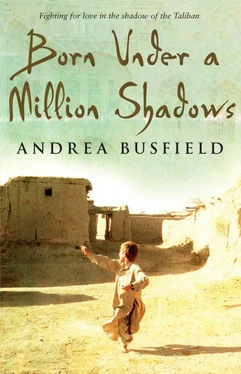

I didn’t blame him. I felt genuinely sorry for him too because sex was usually the only thing Jahid wanted to think about.

“It must be awful never to know love,” Jamilla remarked as Spandi and I walked her to school.

“I guess,” I said.

“I guess,” agreed Spandi.

“Do you think we’ll marry for love?” she asked, which was a bit of a shocker.

“Who? Me and you?”

“Not me and you.” She laughed. “All of us.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” I said.

“I hope so,” admitted Spandi, and we all fell quiet, because in each of our hearts that’s all any of us wanted, if we were honest about it.

The trouble is, in Afghanistan marriage is all about deals. Your father, or in my case mother, arranges the match, sometimes even before you’re born, and you just have to do it—usually to a member of your own family, so I wasn’t sure who I would be married off to, what with all my cousins being boys. But Spandi had girl cousins, so he might end up with one of them, and Jamilla, well, that was a different story. As she got older, the danger grew of her father selling her to someone for drugs. I didn’t like to think about that too much because she was my friend and she was a good girl, so I really hoped she could marry for love because I knew that’s what filled her dreams at night and it’s also what kept the darkness in her life from covering her completely.

“Okay, I’ll have to love you and leave you,” Spandi said with a wink as we turned the corner at Massoud Circle. “I’m going to hang around here for a while and try and sell some cards to the Americans.”

“Okay,” Jamilla said. “Maybe catch you after school.”

“More than likely,” replied Spandi.

“See you later.”

I waved and carried on with Jamilla because I had nothing to sell and nothing else to do.

“If you could marry anyone, who would you marry?”

“Jamilla!” I groaned. “I’m not one of your girlfriends!”

“Come on, you must have thought about it,” she continued in her best whiny girl voice.

“No way, it’s too disgusting!” I lied.

But even as I spoke, pictures of Georgie came running into my mind, followed by Mulallah and then Jamilla, which was worrying.

“I’d marry Shahrukh Khan.”

“The actor?”

“Yes, the actor. He is so good-looking. I watched Asoka on television last night. It was very romantic! Shahrukh Khan plays a prince who falls in love with a beautiful princess called Kaurwaki. But then he thinks she is dead, and he becomes a vicious conqueror because his heart died with her. In the end he marries another woman, who is lovely, but not as lovely as Kaurwaki.”

“A vicious conqueror? Yeah, right. He’s probably gay.”

“He is not!” shrieked Jamilla.

“He’s an actor,” I teased. “He’s nothing more than a very well-paid dancing boy.”

“Take that back!” Jamilla screamed again. “Take it back or—”

“Or you’ll what?”

As Jamilla pushed me into a cart loaded with oranges, a bang as loud as anything I’d ever heard exploded in the air around us, slamming us both to the ground. Beneath our hands and knees the earth trembled with pain as our ears thumped with the shock of it and our hearts burst in knowing fear.

Almost immediately, the smell of burning skin filled the air, even as the world stayed silent. I looked backward, back toward Massoud Circle, where the twisted mess of a Land Cruiser and a Toyota Corolla was being eaten by flames; back to the place where we had stood only seconds before; back to where we’d left Spandi.

Spandi!

My eyes raced over the red-hot flames licking the sky like lizard tongues, past the black and bloody faces of people I didn’t know, around the mess of skin and bone mashed on the ground, over soldiers shocked and still, until I found him, standing far away from me but close enough to touch because my eyes were now concentrating on him, reaching for him, pulling him in.

He was standing near the wreckage of the Corolla. A small boy caught in a gigantic nightmare. Around him the air was dark with smoke, and I watched pieces of metal and black-red body parts float to the ground like feathers as our eyes met and our lives came to a stop. There was no sound I could hear, just the beating of our two hearts connected by our eyes.

Spandi was alive, and I felt my love for him race through my veins, thumping its message inside my body, from my heart to my ears, in heavy thuds. He was my brother, he was as close to family as it got, and I stared that message into his head with all my strength and power as the screaming started.

Beside me I felt Jamilla jump to her feet, and under the noise of the bomb and its killing I heard her whisper his name.

“Spandi…”

Together we ran toward him—just as the bullets began to crack through the air. There was no time to be frightened because there was no time to think—and that’s all fear really is: the worst thoughts you can ever imagine coming real inside your head—so we continued to run, side by side, making the world blur as we passed it, forcing ourselves into the hell before us that was trying to swallow our friend.

Then, far away, I heard the shouts start, Afghan and foreign. It was the terrible sound of scared, angry men roaring their hate and fear into the air as people ran from them or dropped to the ground, hit by invisible bullets. Yet still we ran, and all the time I kept my eyes on Spandi, begging him to stay alive, to keep with me, not to be afraid, because we were coming for him, and I felt him take my words and hold on to them. We were getting so close to him it was almost true.

But then those eyes, those eyes I had known almost my whole life, those eyes that were as much a part of me as they were of him, were snatched away as his head suddenly snapped back. I saw a hole open in his chest, spitting blood onto his shirt as he fell to the ground like a broken toy.

“No!” screamed Jamilla, racing to save him as my legs slowed in pain and shock and the deepest blackness. “No! Please, no! He’s only a boy!”

22

22

AFTER SPANDI’S FATHER found him at the hospital, he brought him back to Khair Khana, to sleep forever next to his mother.

That was a good thing, I knew that, and I was happy for him, because he used to tell me how much he missed his mother when he saw me with mine.

So, yes, I was glad he wouldn’t be alone.

Really, I was.

But then, in the other part of my head, I wasn’t glad, because Spandi was my best friend and now he was gone and somehow, while he was sleeping, I had to carry on with my life, awake and alone.

I couldn’t even think how that would be possible.

From this day on there would be an empty hole in our lives, a hole to add to all the other holes this world had punched into our stomachs, and the more I thought about it, and the more I thought of the place where my friend should be but would never be again, the more I thought I could feel my body collapsing in on itself.

I was being eaten by holes.

I wanted to be strong—strong for him and for his father and for Jamilla, who was almost crazy with grief—but I couldn’t find the energy anymore. It was all too much. It was all so wrong. And I could hardly breathe through my tears.

Spandi was gone.

Yesterday he was here, talking about love and swinging his cards behind him; now he was being carried to the mosque on the shoulders of his father and three other men.

Читать дальше

22

22