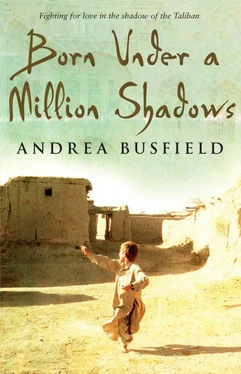

Personally, I didn’t care whether her “resolution” was late or not. I took it as a sign from God that my prayers were working and that Georgie was finally moving in the right direction and away from the flames of Hell that were waiting to eat her.

The next surprise was the fat-bottomed sheep that suddenly turned up in our yard, along with a local butcher to perform the halal act of slaughter. As we all gathered to watch him pronounce the name of God and slit the animal’s throat, May turned her back on the river of blood that quickly turned the snow red.

“Christ, it’s enough to make you vegetarian,” she muttered.

“I thought all you lesbians were anyway,” James joked, earning himself a kick in the shins.

It appeared that in the West, if you were annoyed by just about anything you simply beat the nearest man to you.

My next happy surprise was Haji Khan’s phone call to Georgie, which sent her running up to her room. She emerged thirty minutes later with the stupid grin covering her face that she seemed to save especially for these occasions.

Then Rachel arrived at the house looking fresh and pretty and bringing a similar stupid look to James’s face.

That afternoon Massoud also turned up, and I went with him to take cuts of freshly hacked meat to the homes of Jamilla and Spandi, whose families filled my hands with sugared almonds and papered sweets to take back to the foreigners.

One of the biggest surprises came on the second day of Eid when my aunt arrived at our house with her husband, my cousin Jahid, and their two other kids trailing behind. Although it is expected that Muslims should use the festival to visit their relations, I wasn’t sure this applied to relatives you had recently tried to kill. So, naturally, I was shocked when my mother’s family turned up out of the blue, though this was nothing compared to the shock of seeing my aunt again because it looked like someone had stuck a pin in her skin, letting all the air out and leaving her a shriveled copy of her old self.

At the sight of my aunt, my mother started crying and immediately took her into her arms, which was a lot easier now she was half the size she used to be. Then my aunt started crying too, which set off May and Georgie, and pretty soon all four of the women were reaching for handkerchiefs hidden up the sleeves of their sweaters and coats while all the men, including James, coughed a bit and stood around looking embarrassed.

Apparently, my aunt had also been struck down with the cholera—and by the looks of it she had come off a lot worse than my mother.

In other ways, though, getting cholera was probably the best thing that could have happened to her because as well as sucking the fat from her body the disease had also sucked the ugliness out of her mind. The words that used to fall from her mouth to torment my mother were gone. Now my aunt was not only smaller but quieter than she used to be, and as she sat in my mother’s room holding her hand gently in the palm of her own, I felt a bit sorry for wishing death upon her.

“Fuck, it was awful,” Jahid explained. “Shit everywhere. If I hadn’t seen it with my own eyes, I wouldn’t have believed it. You wouldn’t have thought one person could make so much shit.”

“Well, at least she survived. It’s a pretty bad thing to get over,” I replied, trying to block the image of my aunt shitting out half her body weight in the small house we all used to share.

“True,” replied Jahid. “Two of our neighbors died actually, two of the older men, Haji Rashid and Haji Habib.”

“That’s too bad,” I said, thinking of these two old men who had managed to survive the Russian occupation, the civil war, and the Taliban years only to die in their own shit.

Sometimes, even during Eid, it’s hard to understand God’s plan for us.

As the lights of our festival began to fade and we readied ourselves for normal life again, the final and best surprise of all came.

Taking me by the hand, Georgie led me upstairs to her room, pressing her finger to her lips so I wouldn’t talk. We were obviously on some kind of secret mission, which was kind of exciting on its own. We positioned ourselves on the floor, and she reached for a small radio with a wind-up handle. As it whirred into action, she placed it in front of us.

The soft, low sound of a man speaking in Dari came to my ears; he was introducing phone calls from other Afghans and repeating a list of telephone numbers. The calls were all short and sometimes hard to hear over the crackle of a bad connection, but they all had one thing in common: the faceless voices were asking for lost family members and friends to get in touch.

It was all quite sad, and as I sat there I wondered why Georgie would want me to listen to such misery at the end of such a beautiful Eid. Then the man introduced another load of callers, and I heard Georgie’s voice come dancing into my ears. Her message simply said, “If anyone knows the whereabouts of Mina from Paghman, daughter of Mariya and brother to Fawad, please contact me. Your family is well and happy, and they would love to see you again.”

15

15

IT WAS AGREED that neither Georgie nor I should tell my mother about the radio show because we didn’t want to get her hopes up. As Georgie said, the chances of finding my sister were smaller than finding an honest man in government; but at least a tiny hole of light had now opened in our lives, and it shone twice a week on Radio Free Europe’s In Search of the Lost program.

In the meantime, as I secretly waited for Mina’s return, the world crawled its way through winter, forcing us indoors and turning our noses red. Like summer, winter brings great joy when it comes, but then—maybe because we celebrate it too much at the start—it goes on and on and on, outstaying its welcome until you spend every waking minute praying for it to end.

The freezing cold seemed to be good for Pir Hederi’s business, though. We were now getting up to five calls a day from houses wanting their shopping delivered. What it wasn’t so good for was my toes. After being soaked to the bone in the snow and warmed up again by the bukhari in the shop, I returned home one night to find them swollen and blue. I remembered Pir Hederi’s story about the doomed mujahideen in the mountains and cried myself to sleep worrying that I’d wake up and find ten rotten holes where my toes used to be. My mother went mental when she saw the state of them the next morning and immediately stomped around to Pir Hederi’s to warn him that she would visit a million curses on him unless he took proper care of me. The next day Pir Hederi sent me off on my deliveries with two plastic bags tied to my feet. “Don’t tell your mother,” he said, and handed me a chocolate bar to pay for my silence.

Back at the house, the long gray of winter was also starting to creep into our lives. After a promising start, Haji Khan’s telephone calls had slowly drifted away with the sunshine, and Georgie was becoming increasingly angry, losing her temper every five minutes as she battled with the cigarettes and Haji Khan’s silence. James wasn’t really helping the situation because he was still smoking like a bukhari , but one evening he left the house with a rucksack slung over his shoulder and he explained that because he was really quite a good friend to Georgie he was choosing to spend the next few nights at Rachel’s place in Qala-e Fatullah, which I thought was nice of him. However, I wasn’t as stupid as he obviously thought I was. I guessed the real reason he had gone was that he had already made Rachel his girlfriend.

Читать дальше

15

15