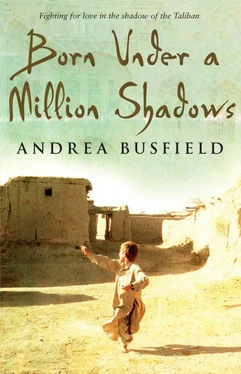

“Your mother needs a lot of water to replace all the fluid she has lost,” May explained, filling yet another glass.

“What’s the matter with her?” I asked, now mixing up the concoction myself after May had shown me how—half a spoon of salt and four spoons of sugar to every glass.

“I’m not sure, Fawad, but I guess she may have cholera. I’ve seen it once before in Badakhshan, and your mother’s symptoms seem to be very similar.”

“What’s chol… chol…”

“Cholera,” May repeated.

“What’s cholera?” I tried again, not liking the hardness of its sound in my mouth.

“It’s a disease caused by bacteria—germs,” explained May. “If I’m right, your mother will be fine, Fawad, but we need to rehydrate her and get her to a hospital as soon as possible. Georgie has called Massoud, and he’s on his way.”

“She’s not going to die, is she?”

“No, Fawad.” May bent down to take my face in her hands. “Your mother won’t die, I promise you that, but she is very, very sick and you have to be a strong little boy right now. Okay?”

“Okay.”

There are a million and one things in this country that can kill you—people and weapons are just the tip of a very large mountain—and one of these things is cholera.

After my mother was laid on the backseat of Massoud’s car and driven to a German hospital in the west of the city with Georgie and May, James tried to take my mind off my worries in the only way he knew how—by filling my head with knowledge about the disease. He opened up his laptop computer, logged on to something called Wikipedia, and typed in the word cholera . A whole page of words in blue letters arrived, and James slowly read them.

The basic diagnosis was that cholera sounded awful, and I cursed my mother’s misfortune, asking Allah to visit a million illnesses on my aunt, who must surely have been the one to infect my mother, being as dirty as an outhouse herself. I knew they didn’t like each other, but to kill her with food was unforgivable.

According to Wikipedia, cholera was quite commonplace in countries like Afghanistan, and the symptoms included terrible muscle and stomach cramps, vomiting, and fever. “At some stage,” read James, translating the words into a language I understood, “the watery shit of the sufferer turns almost clear with flecks of white, like rice. If it’s very bad a person’s skin can turn blue-black, the eyes become sunken, and their lips also turn blue.”

I remembered my mother’s face, and although it had lost its gentle brown color it hadn’t turned blue, which gave me some kind of hope. Of course, I hadn’t been able to examine her shit, though.

“In general,” continued James, “to save someone you have to make them drink as much water as they lose.”

That explained why May had given my mother enough fluid to drown a camel, and as I listened to James reading from the screen of his computer, I developed a newfound respect for the yellow-haired man hater, because May had basically saved my mother’s life. I owed her now.

8

8

“SO, YOU’RE A lesbian, are you?”

As I spoke, May choked on her coffee, breathing in as she spluttered and releasing milky brown liquid through her nose soon after.

It wasn’t a good look.

“Jeez, you’re not shy in coming forward, are you?”

She coughed out the question, then wiped her nose with the sleeve of her tunic. Her cheeks had burst pink, and I looked at her blankly.

“I mean to say, you’re not afraid to speak about what’s on your mind,” she explained, seeing my confusion through the small tears that had collected in the lines hanging around her eyes.

I shrugged. “If I don’t ask, how am I going to learn?” I asked.

“Yeah,” snorted May, “you’ve got a point.”

She shuffled the papers she’d been reading at the desk by the front window, then carefully placed them in a pile before moving in her seat to give me her full attention. I was sitting on the floor trying to place the words of the new national anthem in my head—one of the tasks we had been set at school before it closed for the winter. As it was as long as the Koran, this was no easy task.

“In answer to your question, yes, I am a lesbian,” May admitted.

Her words were carefully spaced, and she eyed me warily. I nodded my head, thoughtfully, and returned to the notebook in front of me.

“Why?” I asked some seconds later.

May shook her head and blinked. “I don’t know why; I just am. It’s not something you decide; you just are, or you’re not. And from a very early age I knew I was.”

“But how will you find a husband if you only love women?”

“Fawad, I will never find a husband.”

“You’re not that bad-looking.”

“I beg your pardon?”

May looked shocked, and I felt a similar stab of surprise that she was shocked because I’d seen her look in the mirror James always checked himself in, the one that hung in the hallway and made your face look longer than it really was, so she must have known.

“I mean, you’re not beautiful like Georgie,” I explained. “But not every man is as beautiful as Haji Khan.”

“My looks aren’t really the issue, Fawad. The issue, the point,” she added quickly as I visibly struggled with another new word, “is I don’t want to find a husband.”

“Then how will you ever have children if you don’t get married?”

“You don’t have to have a husband to have children,” she stated, shaking her head.

“May,” I replied gently, now shaking my own head, “I think you’re very clever and you know a lot of things, like how you knew how to save my mother’s life, but really, this is one of the most stupid things I have ever heard you, or anyone, say.”

May laughed. It brought to her face a whisper of prettiness that was usually missing.

“Things are very different in our culture, young man. In America I can adopt children—take unwanted babies and bring them to my home, where I can love them and raise them. So you see, having a husband is not that necessary.”

“But every woman wants to get married,” I protested.

“Do they now?” May paused slightly to wipe spilled coffee from the desktop before slowly admitting, “Well, maybe you’re right. Actually, Fawad, I’ll let you in on a little secret: I was hoping to get married later this year, but sadly it didn’t work out.”

“Really?”

“Yes, really.” May leaned over the desk, and it caused her breasts to spread on the polished surface like broken cushions. They looked soft and wonderful. “You may remember when you first came here I was a little unhappy. Well, that was because the woman I loved had just told me she no longer wanted to marry me. She had found someone else in America, apparently. A man, as it turned out.”

“I’m sorry…”

“That’s okay,” said May.

“No, I mean, I’m sorry, I don’t understand. You said you wanted to marry a woman . How is that even possible?”

“Oh,” May replied with a smile, “actually it’s very possible. In some places in America men are free to marry men and women are free to marry women.” She rose from her seat to take her coffee cup to the kitchen and playfully pushed my head as she passed by. “That is one of the wonderful things about democracy,” she added, laughing. Then she left the room, leaving me speechless.

Читать дальше

8

8