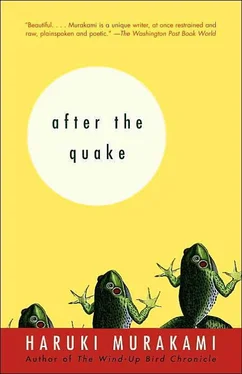

Haruki Murakami - after the quake

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Haruki Murakami - after the quake» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2007, ISBN: 2007, Издательство: Vintage, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:after the quake

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage

- Жанр:

- Год:2007

- Город:New York

- ISBN:0375713271

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

after the quake: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «after the quake»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

An electronics salesman who has been abruptly deserted by his wife agrees to deliver an enigmatic package—and is rewarded with a glimpse of his true nature. A man who has been raised to view himself as the son of God pursues a stranger who may or may not be his human father. A mild-mannered collection agent receives a visit from a giant talking frog who enlists his help in saving Tokyo from destruction. As haunting as dreams, as potent as oracles, the stories in

are further proof that Murakami is one of the most visionary writers at work today.

Haruki Murakami, a writer both mystical and hip, is the West’s favorite Japanese novelist. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Murakami lived abroad until 1995. That year, two disasters struck Japan: the lethal earthquake in Kobe and the deadly poison gas attacks in the Tokyo subway. Spurred by these tragic events, Murakami returned home. The stories in

are set in the months that fell between the earthquake and the subway attack, presenting a world marked by despair, hope, and a kind of human instinct for transformation. A teenage girl and a middle-aged man share a hobby of making beach bonfires; a businesswoman travels to Thailand and, quietly, confronts her own death; three friends act out a modern-day Tokyo version of

. There’s a surreal element running through the collection in the form of unlikely frogs turning up in unlikely places. News of the earthquake hums throughout. The book opens with the dull buzz of disaster-watching: “Five straight days she spent in front of the television, staring at the crumbled banks and hospitals, whole blocks of stores in flames, severed rail lines and expressways.” With language that’s never self-consciously lyrical or show-offy, Murakami constructs stories as tight and beautiful as poems. There’s no turning back for his people; there’s only before and after the quake.

—Claire Dederer

These six stories, all loosely connected to the disastrous 1995 earthquake in Kobe, are Murakami (The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle; Norwegian Wood) at his best. The writer, who returned to live in Japan after the Kobe earthquake, measures his country’s suffering and finds reassurance in the inevitability that love will surmount tragedy, mustering his casually elegant prose and keen sense of the absurd in the service of healing. In “Honey Pie,” Junpei, a gentle, caring man, loses his would-be sweetheart, Sayoko, when his aggressive best friend, Takatsuki, marries her. They have a child, Sala. He remains close friends with them and becomes even closer after they divorce, but still cannot bring himself to declare his love for Sayoko. Sala is traumatized by the quake and Junpei concocts a wonderful allegorical tale to ease her hurt and give himself the courage to reveal his love for Sayoko. In “UFO in Kushiro” the horrors of the quake inspire a woman to leave her perfectly respectable and loving husband, Komura, because “you have nothing inside you that you can give me.” Komura then has a surreal experience that more or less confirms his wife’s assessment. The theme of nothingness is revisited in the powerful “Thailand,” in which a female doctor who is on vacation in Thailand and very bitter after a divorce, encounters a mysterious old woman who tells her “There is a stone inside your body…. You must get rid of the stone. Otherwise, after you die and are cremated, only the stone will remain.” The remaining stories are of equal quality, the characters fully developed and memorable. Murakami has created a series of small masterpieces.

Copyright 2002 Cahners Business Information, Inc. Amazon.com Review

From