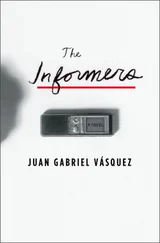

‘Hey, Yammara, I have to listen to this,’ he told me. ‘You wouldn’t know anybody who could lend me a cassette player?’

‘Doesn’t Don José have one?’

‘No, he hasn’t got anything,’ he said. ‘And this is urgent.’ He rapped on the plastic case a couple of times. ‘And it’s private as well.’

‘Well,’ I said, ‘there is a place a couple of blocks away, couldn’t hurt to ask.’

I was thinking of the Casa de Poesía, the only plausible option in the neighbourhood at that time of day. It was the former residence of the poet José Asunción Silva, now converted into a cultural centre where they hold readings and workshops. I used to go there quite often all through my degree. One of its rooms was a unique place in Bogotá: there, all sorts of word-struck people would go to sit on soft leather sofas, near fairly modern stereo equipment, and listen to now legendary recordings: Borges reading Borges, García Márquez reading García Márquez, León de Greiff reading León de Greiff. Silva and his work were on everybody’s lips those days, for in that barely begun 1996 the centenary of his suicide was going to be commemorated. ‘This year,’ I’d read in an opinion piece by a well-known journalist, ‘statues will be raised to him all over the city, and all the politicians will mention his name, and everyone will wander around reciting his “Nocturne”, and everybody will take him flowers at the Casa de Poesía. And Silva, wherever he might be, will find this curious: this prudish society that humiliated him, that pointed their fingers at him every chance they got, paying homage to him now as if he were a head of state. The ruling class of our country, haughty charlatans, have always liked to appropriate culture. And that’s what’s going to happen with Silva: they are going to appropriate his memory. And his real readers are going to spend the whole year wondering why the hell they don’t leave him alone.’ It’s not impossible that I had that column in mind (in some dark part of my mind, deep down, very deep, in the archive of useless things) at the moment I chose that place to take Laverde.

We walked the two blocks without saying a word, with our eyes on the broken paving stones or on the dark green hills that rose in the distance, bristling with eucalyptus and telephone poles like the scales on a Gila monster. When we got to the entrance and walked up the stone steps, Laverde let me go in first: he’d never been in such a place, and he acted with the misgivings, the suspicions, of an animal in a dangerous situation. There were two high-school students in the room with the sofas, a couple of teenagers listening to the same recording and every once in a while looking at each other and laughing indecently, and a man in a suit and tie, with a faded leather briefcase on his lap, snoring shamelessly. I explained the situation to the woman at the desk, who was no doubt used to exotic requests, and she looked me over through squinting eyes, seemed to recognize me or identify me as a person who’d been there many times before, and held out her hand.

‘Let’s see, then,’ she said unenthusiastically. ‘What is it you want to play?’

Laverde handed her the cassette like a soldier surrendering his weapon, with fingers visibly smudged with blue billiard chalk. He went to sit down, submissive as I’d never seen him before, in the armchair the woman pointed him to; he put on the headphones, leaned back and closed his eyes. Meanwhile, I was looking for something to occupy my time while I waited, and my hand picked up Silva’s poems as it might have chosen any other recording (I must have given in to the superstition of anniversaries). I sat down in my chair, picked up the corresponding headphones, adjusted them over my ears with that feeling of putting myself beyond or closer to real life, of starting to live in another dimension. And when the ‘Nocturne’ began to play, when a voice I couldn’t identify — a baritone that verged on melodrama — read that first line that every Colombian has pronounced aloud at least once, I noticed that Ricardo Laverde was crying. One night all heavy with perfume , said the baritone over a piano accompaniment, and a few steps away from me Ricardo Laverde, who wasn’t listening to the lines I was listening to, wiped the back of his hand across his eyes, then his whole sleeve, with murmurs and music of wings . Ricardo Laverde’s shoulders began to shake; he hung his head, brought his hands together like someone praying. And your shadow, lean and languid , said Silva in the voice of the melodramatic baritone, And my shadow, cast by the moonbeams . I didn’t know whether to look at Laverde or not, whether to leave him alone in his sorrow or go and ask him what was wrong. I remember having thought that I could at least take off my headphones, a way like any other of opening a space between Laverde and me, of inviting him to speak to me; and I remember deciding against it, having chosen the safety and silence of my recording, where the melancholy of Silva’s poem would sadden me without putting me at risk. I guessed that Laverde’s sadness was full of risks, I was afraid of what that sadness might contain, but my intuition didn’t go far enough to understand what had happened. I didn’t remember the woman Laverde had been waiting for, I didn’t remember her name, I didn’t associate him with the accident at El Diluvio, but I stayed where I was, in my chair and with the headphones on, trying not to interrupt Ricardo Laverde’s sadness, and I even closed my eyes so I wouldn’t bother him with my indiscreet gaze, to allow him a certain privacy in the middle of that public place. In my head, and only in my head, Silva said: And they were one single long shadow . In my self-contained world, where all was full of the baritone voice and Silva’s words and the decadent piano music that enveloped them, a time went by that lengthens in my memory. Those who listen to poetry know how this can happen, time kept by the lines of verse like a metronome and at the same time stretching and dispersing and confusing us like dreamtime.

When I opened my eyes Laverde was no longer there.

‘Where did he go?’ I said with the headphones still on. My voice reached me from afar, and my absurd reaction was to remove the headphones and repeat the question, as if the woman behind the desk wouldn’t have heard it properly the first time.

‘Who?’ she asked.

‘My friend,’ I said. It was the first time I described him as such, and I suddenly felt ridiculous: no, Laverde was not my friend. ‘The guy who was sitting there.’

‘Oh, I don’t know, he didn’t say,’ she replied. Then she turned away, checked the sound equipment; mistrustfully, as if I were complaining about something she’d done, she added, ‘And I gave the cassette back to him, OK? You can ask him.’

I left the room and looked quickly through the building. The house where José Asunción Silva had spent his final days had a bright patio in the middle, separated from the corridors that framed it in narrow glass windows that wouldn’t have existed in the poet’s time and now protected the visitors from the rain: my footsteps, in those silent corridors, resounded without echoes. Laverde was not in the library, or sitting on the wooden benches, or in the conference room. He must have left. I walked towards the narrow front door to the house, past a security guard in a brown uniform (he wore a tilted cap, like a thug in a movie), past the room where the poet had shot himself in the chest a hundred years earlier, and as I came out onto 14th Street I saw that the sun was now hidden behind the buildings of 7th Avenue, saw that the yellow streetlights were timidly starting to come on, and saw Ricardo Laverde, in his long coat, his head down, walking two blocks from where I was, already almost at the billiard club. I thought: And they were one single long shadow , absurdly the line came back to mind; and in that same instant I saw a motorbike that had been still until now on the pavement. Maybe I saw it because its two riders had made a barely perceptible movement: the feet of the one on the back rising up onto the stirrups, his hand disappearing inside his jacket. Both of them were wearing helmets, of course; and the visors of both, of course, were dark, a large rectangular eye in the middle of the large head.

Читать дальше