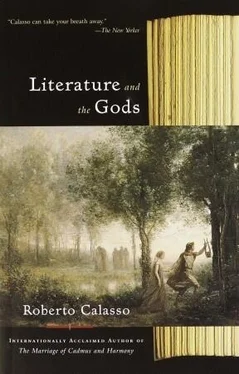

What was going on? “A descent into Nothingness,” which we could liken to a saison en enfer , but not of the torrid and turbulent variety Rimbaud experienced. On the contrary, from the outside there was nothing to be seen: like a building that dissolves into rubble and dust while the façade remains intact — until one day the windows are empty sockets framing the sky behind them. Something chilling and secretive was happening. Mallarmé describes it thus: “I really have decomposed, and to think that this is what it takes to have a vision of the universe that is really whole! Otherwise, the only wholeness one feels is that of one’s own life. In a museum in London there is an exhibit called ‘The Value of a Man’: a long coffinlike box with lots of compartments where they’ve put starch — phosphorus — flour — bottles of water and alcohol — and big pieces of gelatin. I am a man like that.” Once again we sense the all-pervasive, slightly nauseous smell of formaldehyde. But who is it describing himself in this way? The obscure English teacher — or someone else? Or who in him?

So it is that once again the Progenitor, the Prajāpati of the  , appears on the scene: exhausted, dislocated, breath rattling in his throat, it is he who had to decompose before anything else could appear and exist. Including the gods, for they too are beings with a shape and hence do not know the spasm of the “indefinite,” anirukta , from which they sprang and which glows within them. But this time, shrugging off the fog of centuries, Prajāpati finds himself transposed into the golden age of positivism, when man is no more than physics plus chemistry, and consciousness but a vague by-product of the higher functions, something nobody has time to be bothered with. This too the Progenitor would have to put up with, one more insult in his interminably long life. But why had Mallarmé gone looking for Prajāpati, without even knowing who he was?

, appears on the scene: exhausted, dislocated, breath rattling in his throat, it is he who had to decompose before anything else could appear and exist. Including the gods, for they too are beings with a shape and hence do not know the spasm of the “indefinite,” anirukta , from which they sprang and which glows within them. But this time, shrugging off the fog of centuries, Prajāpati finds himself transposed into the golden age of positivism, when man is no more than physics plus chemistry, and consciousness but a vague by-product of the higher functions, something nobody has time to be bothered with. This too the Progenitor would have to put up with, one more insult in his interminably long life. But why had Mallarmé gone looking for Prajāpati, without even knowing who he was?

Here modern and primordial meet and a spark is struck: to create a work of absolute literature one must reunite oneself with the indistinct time before the gods were born, the time when Prajāpati elaborated, with that “ardor” or heat that is called tapas . his desire for an outward existence that would be both visible and palpable. When Mallarmé spoke of the fire beneath his alchemist’s crucible, he was referring to that same tapas . And in fact he had always felt drawn to this obscure figure, always been ready to be led that way, ready to have the elements of his body deposit out into those gloomy chemical compartments that remind us at once of pharmacy and of morgue. But who did the leading? The poet answers: “Destruction was my Beatrice.”

In Mallarmé’s apartment there was a Venetian mirror, a talisman. During the process that had “dragged” him down “into the Shadows,” he felt he was sinking “desperately and infinitely” into that mirror. For now it no longer reflected the poet looking into it and studying his reflection there. But one day Mallarmé would surface in the mirror again, like a piece of flotsam in a pond. He looked at himself, recognized himself — and went back to his old life. But he knew that something had changed — and his closest friend, Cazalis, sensed it too: he was no longer, Mallarmé wrote to him, the “Stéphane you knew — but a disposition of the Spiritual Universe to see itself and develop itself, through what I was.” These words, which in a newsy letter to a friend sound, as it were, calmly delirious, will seem perfectly plausible and even self-evident if we think of them as a description of an episode in the life of Prajāpati. Mallarmé was trying to give a name to a process that had not been recorded in the lexicon of the tradition he worked in. Yet he kept trying, as if with a presentiment that that impossible path was the only one available to him. But what was the link that welded Mallarmé to that being, Prajāpati, of whom the West knew absolutely nothing then (not one of the  had been translated at the time)?

had been translated at the time)?

A word: manas , “mind” (the Latin mens ). The  say: “Prajāpati is, so to speak, the mind,” or elsewhere, “The mind is Prajāpati.” If we had to define that characteristic which makes Mallarmé so radically different from the poetry that came before — and after — we would have to say: never had poetry been so magnificently superimposed upon the most elementary and mysterious fact of all — that a certain fragment of matter is endowed with that quality which is like no other, that is, on the contrary, the very medium in which every quality and every likeness appear, and which is called “consciousness.”

say: “Prajāpati is, so to speak, the mind,” or elsewhere, “The mind is Prajāpati.” If we had to define that characteristic which makes Mallarmé so radically different from the poetry that came before — and after — we would have to say: never had poetry been so magnificently superimposed upon the most elementary and mysterious fact of all — that a certain fragment of matter is endowed with that quality which is like no other, that is, on the contrary, the very medium in which every quality and every likeness appear, and which is called “consciousness.”

As Proust would one day write to Reynaldo Hahn, it is not true that in Mallarmé images disappear. No, they are “still images of things, since we would never be able to imagine anything else, only that they are reflected, as it were, in a smooth dark mirror of black marble.” And that “black marble” is the mind. In Mallarmé the material of poetry is brought back, with unprecedented and as yet unrepeated determination, to mental experience. Shut away in an invisible templum , the word evokes, one after another, simulacra, mutations, events, all of which issue and disperse in the sealed chamber of the mind, where the primordial crucible burns. This is the place the reader is invited to discover, but before he can penetrate it he will have to make the same journey the poet did. This is what Mallarmé meant when he insisted so stubbornly that his poetry was composed of effects and suggestions that must act as if on a mental keyboard. Never state the thing, but the resonance of the thing. Why this obsession? Many recent readers have taken this precept of Mallarmé’s to imply a reduction of the world to the word, with the inevitable consequence that all becomes entirely self-referential and self-sufficient. But this is not the case: on the contrary, such a vision impoverishes and frustrates what is secretly at work in this poetry. The premise behind this interpretation is one that governs much of our world today — indeed, that makes it possible for that world to operate — but that at the same time leaves it unable to grasp a great deal of what is essential. In its most concise form this premise declares that thought is language. More ambitiously it claims that the mind is language. But we do not think in words. Or rather, we sometimes think in words. Words are scattered archipelagos, drifting, sporadic. The mind is the sea. To recognize this sea in the mind seems to have become something forbidden, something that the presiding orthodoxies, in their various manifestations, whether scientistic or merely commonsensical, instinctively avoid. Yet this is the crucial parting of the ways. It is at this crossroads that we decide in which direction knowledge will go.

A question presents itself: in what way, then, did the tremendous upheaval Mallarmé experienced between May 1866 and May 1867 manifest itself in his poetry? Let’s look at the sonnet that is known as “in ix , because it includes a sequence of difficult rhymes in ix . The poem is defined by Mallarmé as “a sonnet allegorical of itself,” and this definition immediately serves as a warning that we are on the threshold of something that had never been tried before. In an age where allegory was becoming no more than an appendage of the department of public works, used mainly in the conception of those clumsily complacent monuments that celebrate some capitalized abstraction, as, for example, Humanity, Country, Progress, Victory, or whatever — in such an age merely to claim that a sequence of words was offering something “allegorical of itself” was a gesture of impertinent defiance. Equally challenging was the decision to build the sonnet around rhymes in ix —rhymes among the rarest in the French language, so much so that while working on the poem Mallarmé had to ask his friends if anyone knew the exact meaning of the word ptyx , which he needed for a rhyme. But though this may be the most immediately noticeable aspect of the poem, it is not the most important.

Читать дальше

, appears on the scene: exhausted, dislocated, breath rattling in his throat, it is he who had to decompose before anything else could appear and exist. Including the gods, for they too are beings with a shape and hence do not know the spasm of the “indefinite,” anirukta , from which they sprang and which glows within them. But this time, shrugging off the fog of centuries, Prajāpati finds himself transposed into the golden age of positivism, when man is no more than physics plus chemistry, and consciousness but a vague by-product of the higher functions, something nobody has time to be bothered with. This too the Progenitor would have to put up with, one more insult in his interminably long life. But why had Mallarmé gone looking for Prajāpati, without even knowing who he was?

, appears on the scene: exhausted, dislocated, breath rattling in his throat, it is he who had to decompose before anything else could appear and exist. Including the gods, for they too are beings with a shape and hence do not know the spasm of the “indefinite,” anirukta , from which they sprang and which glows within them. But this time, shrugging off the fog of centuries, Prajāpati finds himself transposed into the golden age of positivism, when man is no more than physics plus chemistry, and consciousness but a vague by-product of the higher functions, something nobody has time to be bothered with. This too the Progenitor would have to put up with, one more insult in his interminably long life. But why had Mallarmé gone looking for Prajāpati, without even knowing who he was? had been translated at the time)?

had been translated at the time)? say: “Prajāpati is, so to speak, the mind,” or elsewhere, “The mind is Prajāpati.” If we had to define that characteristic which makes Mallarmé so radically different from the poetry that came before — and after — we would have to say: never had poetry been so magnificently superimposed upon the most elementary and mysterious fact of all — that a certain fragment of matter is endowed with that quality which is like no other, that is, on the contrary, the very medium in which every quality and every likeness appear, and which is called “consciousness.”

say: “Prajāpati is, so to speak, the mind,” or elsewhere, “The mind is Prajāpati.” If we had to define that characteristic which makes Mallarmé so radically different from the poetry that came before — and after — we would have to say: never had poetry been so magnificently superimposed upon the most elementary and mysterious fact of all — that a certain fragment of matter is endowed with that quality which is like no other, that is, on the contrary, the very medium in which every quality and every likeness appear, and which is called “consciousness.”