MALLARMÉ “Zeus était un pur nom, à la faveur de quoi il leur fût possible de parler de la divinité, inscrite au fond de notre être.”

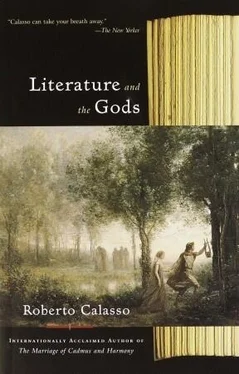

The deviation is evident and the consequences farreaching. On the one hand we have Cox, who treats the Greeks as children allowed only a confused glimpse of that truth which will only become available through the Christian revelation, the appearance of Him who truly is that Person “in whom we live and move and have our being,” as the King James Version so eloquently translates Saint Paul’s words to the Athenians. On the other we have Mallarmé, who refers to an impersonal entity of which he says only, in words both sober and mysterious, that it is “inscribed in the very ground of our being.” But what did Mallarmé mean when he used the word “divinity”? Rather than to the gods, who in their Parnassian version could all too easily be suspected of heralding some noble kind of rhythmic gymnastics, or at best looking forward to Isadora Duncan, Mallarmé was always drawn to a neutral form of the divine, an underlying ground beneath everything else, nourishing everything else and from which all else springs, a ground at once cosmic and mental, equally shared out, and of which he would one day write: “There must be something occult in the ground of everyone; I firmly believe in something hidden away, a closed and secret signifier, that inhabits the ordinary.” But before gaining access to that “closed and secret signifier,” which was to be his entire opus, Mallarmé was to go through a ferocious, silent, and protracted mental drama that culminated in a “terrible struggle with that old and evil plumage, happily brought to earth, God.” To be more precise: “That struggle took place on his bony wing, the which, in more vigorous death throes than I had thought possible from him, had dragged me into the Shadows.” The first thing we can say about this duel is that it takes place just months before the gruesome descriptions of repeated battles between Maldoror and his Creator, as for example when the latter sees “the annals of the heavens knocked off their pedestal,” while Maldoror applies his “four hundred suckers to the hollow of his armpit,” causing him to “let out terrible screams.”

Before approaching any underlying divine ground, then, one first had to kill a being called God, an old and tenacious bird who clung to his antagonist throughout long-protracted death throes. And what would happen when the fight was over? Again, in a letter from the same period, Mallarmé recounts: “I had just drawn up the plan of my entire life’s work, having found the key to myself — the keystone, or center, if you like, so as not to mix ourselves up with metaphor, the center of myself, where I dwell like a sacred spider, on the principal threads already spun from my mind, and with the help of which I will weave, at the crossing points , some marvelous laces, which I can foresee and which already exist in the bosom of Beauty.” Like the “bony wing,” this “sacred spider” also belongs to the zoology of Lautréamont. What went on in the secret depths of the mind seemed anxiously to be awaiting this new teratologist, the visionary who would expand the animal realm to include new kinds of monsters.

But why does Mallarmé call himself a “sacred” spider? Is it that, having brought down the old plumage, God, he plans, in a delirium of omnipotence, to take his place? Or was it rather a delirium of impotence that afflicted the young English teacher, secluded as he was in the gloomiest of provinces? Neither one nor the other. In referring to himself as a “sacred spider,”

Mallarmé was doing no more, no less, than performing his function as a poet, which is first of all that of being precise. What he couldn’t know was that he wasn’t speaking of himself, but of the Self, the ā tman .

Let us open the  :

:

“As a spider sends forth its thread, as small sparks rise from the fire, so all senses, all worlds, all gods, all beings, spring from the Self.”

And another  speaks of a “single god who like a spider cloaks himself in the threads spun from the primordial matter [ pradh ā na ], according to his nature

speaks of a “single god who like a spider cloaks himself in the threads spun from the primordial matter [ pradh ā na ], according to his nature  .” And another again says: “As a spider spins out and swallows up his thread, as the grasses spring from the earth, as the hairs from the head and body of a living being, so everything here springs from the indestructible.”

.” And another again says: “As a spider spins out and swallows up his thread, as the grasses spring from the earth, as the hairs from the head and body of a living being, so everything here springs from the indestructible.”

Unfamiliar with the Vedic texts, barely initiated in the rudiments of Buddhism by his friend Lefébure and always punctilious in rejecting any direct connection with it (“the Nothing, which I arrived at without knowing Buddhism,” he says), Mallarmé was clearing a path toward something that had no name in the lexicon of his times, but within which he would always live and work. It was the same thing to which three years later he planned to dedicate a thèse d’agrégation , of which only the title now remains: De divinitate . But we do know that Mallarmé saw in that thesis both the outcome and the convalescence of a long, devastating process that had transformed him into another being.

The acute, precipitous phase of that process lasted a year, from May 1866 to May 1867. Mallarmé was then a twenty-four-year-old English teacher at the high school in Tournon, moving later to Besançon, where the climate is “black, damp, and icy.” He came from a family who had long been and still were Public Registry officials. In his family, to “have a career” meant to have a career in the Registry Office. Mallarmé was the first to betray his breed, choosing poetry. Already he had sensed that the world around him had “a kitchen smell.” As a poet, his main task would be to work Baudelaire’s furrow and push it that little bit further. This he had already started to do, with great mastery, when he wrote “L’Azur” and “Brise marine.” Then, in the spring of 1866, Mallarmé spends a week in Cannes and something happens —a sort of primordial event that looks forward to Valéry’s “night in Genoa.” His first mention of it comes in a letter to Cazalis on April 28th.

Mallarmé explains: “Quarrying the verse to that point I encountered two chasms, which bring me to despair. One is Nothingness.” This “crushing thought” forced him to abandon writing poetry. But immediately afterwards Mallarmé launches into a paragraph that lays a sort of metaphysical foundation for the poetry he was yet to write: “Yes, I know , we are nothing but vain forms of matter — yet sublime too when you think that we invented God and our own souls. So sublime, my friend! that I want to give myself this spectacle of a matter aware, yes, of what it is but throwing itself madly into the Dream that it knows it is not, singing the Soul and all those divine impressions that gather in us from earliest childhood, and proclaiming, before the Nothingness that is the truth, those glorious falsehoods!” The threads that interweave in this sentence would go on spinning out until Mallarmé’s death. And likewise the ambiguities: above all in that verb s’élançant (“throwing itself”), in which converge both the subject who wants to give himself “this spectacle of a matter,” etc., and the matter itself observing its own behavior.

At this point we realize we have been abruptly introduced into that geometrical locus called Mallarmé. Immediately the atmosphere is both chemical — a vivisection laboratory, in fact — and alchemical: the heat of the opus alchymicum . This, then, is the great atmosphere of décadence , something that sprang before anything else out of a dissociation of forms and psyche. Mallarmé was to become at once the high priest and the scientist of this process, which, in fact, was already at work. In July Mallarmé observes, once again for the benefit of Cazalis: “For a month now I have been in the pure glaciers of aesthetics — having discovered Nothingness I have found the Beautiful.” And the work starts to take shape, not une oeuvre now, but “le Grand Oeuvre , as our forebears the alchemists used to say.” A long period of elaboration would be required: “I shall give myself twenty years to bring it [the opus] to completion, and the rest of my life will be given over to an Aesthetics of Poetry.”

Читать дальше

:

: speaks of a “single god who like a spider cloaks himself in the threads spun from the primordial matter [ pradh ā na ], according to his nature

speaks of a “single god who like a spider cloaks himself in the threads spun from the primordial matter [ pradh ā na ], according to his nature  .” And another again says: “As a spider spins out and swallows up his thread, as the grasses spring from the earth, as the hairs from the head and body of a living being, so everything here springs from the indestructible.”

.” And another again says: “As a spider spins out and swallows up his thread, as the grasses spring from the earth, as the hairs from the head and body of a living being, so everything here springs from the indestructible.”