Minae Mizumura - A True Novel

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Minae Mizumura - A True Novel» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Other Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A True Novel

- Автор:

- Издательство:Other Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A True Novel: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A True Novel»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A True Novel

The winner of Japan’s prestigious Yomiuri Literature Prize, Mizumura has written a beautiful novel, with love at its core, that reveals, above all, the power of storytelling.

A True Novel — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A True Novel», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I led Taro into Mrs. Utagawa’s room. Perhaps it all worked out because Taro was wearing Yuko’s pajamas. And because he smelled nice from the soap. His skin also had a reddish glow after being scrubbed so hard, and his shiny black hair, a little too long for a boy, covered part of his forehead. I had noticed his features before, but I’d never imagined he was so cute-looking—more like a girl, in a way.

Taro stood in the doorway, his almond-shaped eyes wide open. Once he saw Yoko sitting there next to her grandmother, arranging the contents of the sewing chest, he just watched her. Yoko looked up. Surprised at his appearance, she leaped up, letting everything fall off her lap, and almost skipped over to him.

“Good! You’re so clean now!” she said, as she leaned her face close to his neck and, flaring her nose, breathed in. “Mm, you smell nice!” He did the same. Maybe because she burned like a little furnace, Yoko’s face and neck always smelled a bit like warm milk. I would guess that’s what Taro smelled then. It didn’t occur to me to wonder how things would work out for the children in the future. I had been so anxious about what Taro might be going through, I just felt relieved and exhausted.

Yoko was a good head shorter than Taro, and her frizzy hair brushed against his chin. Taro, elated, scowled to hide it.

I gave up my hour of reading that day.

It was late by the time I served the snack, which I had some of myself. I needed to wash Taro’s clothes, but somehow it didn’t seem right to use the machine, so I did it by hand. When I went back to Mrs. Utagawa’s room, I found Taro and Yoko at the old lady’s low desk with a schoolbook in front of them. I noticed the three white pebbles lined up on the edge of the desk. Yoko was confidently explaining their homework to him. The two of them were still in the same class, though in a new building, nearer by: their school had been divided up as new children flooded into the neighborhood. While I ironed Taro’s clothes and underwear to dry them, I could hear Yoko chattering about one thing after another. Even when I started mending his clothes, her voice never stopped. At some point, the two had gone into the playroom at the far end of the main room, from where the same voice came at more of a distance. I strained my ears, but I could hardly ever hear Taro’s voice.

Yoko continued her excited chatter. This was Taro’s initiation into a relationship in which he would wander ever afterward between bliss and pain.

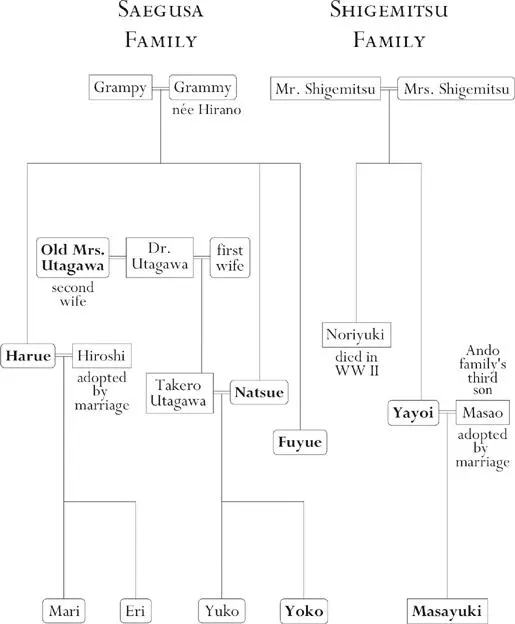

The Families

A True Novel: Volume II

5. Lightbulbs

YOKO WAS LONELY. This didn’t really occur to us until her grandmother and I heard her chattering away with such animation that day. She couldn’t go and play at a friend’s house since that would mean leaving her grandmother alone, and bringing a friend home would probably have seemed doubly wrong—awkward for the friend and an imposition on her grandmother. At the local elementary school her classmates were a motley collection, the children of farmers, cooks, station-front shop owners, carpenters, and real estate agents—few of them the kind to become close enough for her to ask over in the first place. Her mother, who was gone all day, had drummed into her that she mustn’t make friends with “vulgar” children. Yoko herself, although she was sickly, and shy around strangers, was the classic example of someone who at home turned into a little autocrat: she certainly lorded it over her grandmother and me. Making friends didn’t come easily to her. Still, she must have been lonely with no one but an old lady and a housemaid for playmates. That day when old Mrs. Utagawa invited Taro into the house, I’m sure she did so on an impulse, just to give him a break from the usual grind; but to Yoko the invitation meant that here was a ready-made friend, one who had her grandmother’s approval.

Then came the incident of the following day. If that hadn’t happened, I doubt if Taro would ever have become such a fixture in the Utagawa household. And I doubt if Mrs. Utagawa would have taken it on herself to become his protector to the extent that she did.

The afternoon this occurred, after she came home from school we couldn’t find Yoko anywhere in the house. She’d called out a cheery greeting, and her red leather backpack was right by her grandmother’s low desk where it was supposed to be, but there was no sign of its owner. She wasn’t upstairs or in the toilet. Mrs. Utagawa hastily opened the glass sliding doors that overlooked the front yard, then the front door facing the gate, calling “Yoko! Yoko!” in a loud voice, but there was no answer. Finally when she called from the back door, there was a response.

“Over here, Grandma!” Yoko’s high-pitched voice came from the direction of the Azuma house. Mrs. Utagawa and I exchanged looks and thrust our feet into wooden clogs, wondering what on earth was going on. We hurried past the wooden fence to find the sliding doors on the veranda wide open and Yoko’s little sandals lined up neatly on the stepping-stone beneath.

Mrs. Utagawa went and looked inside the small four-and-a-half-mat tatami room. For a second she seemed unable to take in what was going on—and then the blood drained from her face.

The day before, I had missed it—either O-Tsune had blocked my view when she came toward me, or else I just didn’t try to look in—but at that moment I saw just how unsavory that cluttered room was. In the center was a flesh-colored mound, a heap of tiny arms and legs. Looking more closely, I saw naked rubber dolls with blond hair, each one about the length of my hand. They lay piled up by the dozen, surrounded by fluffy nylon cloth, thread, and ribbons of blue, orange, and pink. But that alone wouldn’t have accounted for Mrs. Utagawa’s turning so pale. What was genuinely obscene, made worse by the mound of naked rubber dolls, was a scattering of pages that had been torn from old magazines—men’s magazines—and crumpled into balls for packing. Black-and-white photographs of women suspended upside down in their underwear; garish woodblock prints of naked young women, their hair piled high, being assaulted with bamboo spears … Fragments of such scenes were like poisonous thorns, stabbing at my eyes.

In the midst of this mess Yoko was sitting with her knees bent inward and feet splayed, as usual, her skirt flaring around her. To show off what she was doing, she grabbed a doll by the legs, turned around, and held it out for her grandmother to see.

As my shock wore off, it sank in that Yoko was just helping out, putting skirts on rubber dolls. When she went over to ask if Taro could come out and play, they must have told her that he had work to do and couldn’t leave till the job was done. So she pitched in, determined to do her bit so that he could play sooner. Since she was only eight years old and clumsy to begin with, she couldn’t have been much use, but O-Tsune’s character was so twisted I’m sure it tickled her to think of an Utagawa girl doing such work. Instead of stopping her, she probably egged her on. No one else from the Utagawa family had paid the Azumas a visit since they moved in, and I doubt very much that she expected Mrs. Utagawa to show up. Like most people, she knew only her own world and could never have imagined how appalled we might be to catch Yoko in these circumstances.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A True Novel»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A True Novel» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A True Novel» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.