Minae Mizumura - A True Novel

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Minae Mizumura - A True Novel» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Other Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A True Novel

- Автор:

- Издательство:Other Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A True Novel: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A True Novel»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A True Novel

The winner of Japan’s prestigious Yomiuri Literature Prize, Mizumura has written a beautiful novel, with love at its core, that reveals, above all, the power of storytelling.

A True Novel — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A True Novel», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

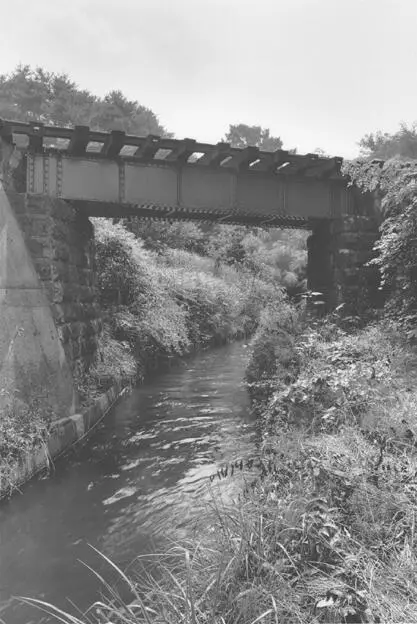

KOUMI LINE

I would say O-Hatsu has seen more changes in her lifetime than I have. After all, she lived for most of the century when this country was changing faster than it ever had before. Even so, I have a feeling that the inside of her head has remained much the same as when she was a girl. By “the inside of her head” I mean the way she sees the world around her—the language she uses to make sense of it. In my case, the very way I looked at the world and the words I used to understand it had altogether changed.

O-Hatsu has always been good to me, just as she was good to my mother. So for the past few years I’ve made a point of paying her a visit at New Year’s. I always think it might be the last time I’ll set eyes on her, on her weather-beaten, wrinkled face. She still lives in the same place where my mother’s parents’ house once was. But the house I knew as a child, with its thatched roof, was torn down decades ago, and even the two-story house that replaced it is gone. The present building, put up by O-Hatsu’s grandchildren a year or so ago, is utterly modern, with radiant floor heating and various other amenities. When I go to visit, she’s usually sitting on the sofa in the warm living room, watching television and nibbling on some Pockys, those chocolate-coated sticks. With a knitted woolen cap on her head, she sits there with her legs folded under her as though she were on a tatami mat rather than a sofa.

“Auntie!” I call out—loudly, since her hearing isn’t good. She turns around and sees me standing there.

“Well, if it isn’t Fumiko,” she says.

The voice belongs to someone who knew me as a child; someone who hasn’t changed much at all since then. More even than Mount Asama or the Chikuma River, the sound of that voice—the accent the same as ever—is a direct link to my past. But it also reminds me how much I’ve changed.

Invariably, it takes me back to those winter nights fifty years ago.

I can hear O-Hatsu and my mother talking in low voices as they sit sipping tea by the hearth. I can also hear the crackling of the mulberry roots burning. Outside, it’s windy and cold. Just a little girl, I’m bent over a pile of acorns I gathered that day, first wiping them with an old rag and then stringing them together on a thread. I can feel the mountain winter with my whole body at moments like these. When I raise my eyes, I see their patient faces, the faces of people who’ve endured years of hard work, in flickering light and shadow. Looking at them, my heart fills with a mixture of comfort and concern.

THE HOME MY mother came from was barely a fifteen-minute walk from the house where I grew up. After she moved into her husband’s house as a new bride, she didn’t dare return to her parents’ except on special days like New Year’s or the Bon festival. That changed when my father went off to the war and my mother was left to look after her in-laws. With no one else to help her, she had an excuse to visit her own home more often. Those winter evenings when, after dinner, she and I headed over to my grandparents’ place are still fresh in my memory. My mother held my hand, and in her other hand she carried a pole with a lantern dangling at the end of it as we made our way down the hard, frozen lane, shivering.

My mother was always tense and silent as we trudged along. Only when there was trouble could a bride go back to her former home. When we finally got there, she’d blow out the lantern and nervously, her shoulders hunched forward, slip into the side entrance of the house, which was floored with packed earth like ours.

“Good evening to you,” my mother called out. That was the way people in those parts greeted each other at that hour.

“Oh! Good evening to you too,” O-Hatsu said cheerfully as she appeared at the entrance. Her voice was always bright, which was unusual in a farmwife. Thinking about it now, she must have known that it wasn’t good news we were bringing, but she always greeted us warmly anyway. That brightness was a quality we all admired in her. Her mother-in-law—my maternal grandmother—was unhealthy and died before the war, leaving O-Hatsu the sole woman in the household. The confidence she developed managing on her own became part of her character. Some people thought she was bossy, but in my eyes she was just someone you could depend on.

By the time my mother had sat herself down on the raised wooden floor, tears already stood in her eyes, she was so ready to cry. O-Hatsu’s bright, sympathetic voice released all the misery she kept bottled up the rest of the time.

“Now, now, stop your cryin’. What’s the matter this time? Tell me what happened.” O-Hatsu would go over to her, take her hand, make her stand up, and lead her to sit by the fire.

For my mother, O-Hatsu was more than just a sister-in-law; she thought of her almost as a parent. O-Hatsu had married the eldest son, and my mother was the youngest of eight.

Once at the hearth, she’d plop down, pull out a small hand towel from the waist of her trousers, and sit there sobbing and sobbing.

My mother was a good person, but she wasn’t strong. After the war robbed her of a husband, she buckled, body and soul, under the weight of her troubles; she didn’t know how to carry on by herself. She started to ask favors of her own family. Just little things: a bit of money to get her through the end of the year, a helping hand from one of the boys for a day or two. Her eldest brother was too old to be called up, and two of his four sons were too young, so luckily, they still had an unusual number of men living there. In our house, the only man left when my father went off to fight was Grandpa, and soon afterward he had a mild stroke and turned so doddery he barely had the strength to chop up the mulberry bushes for firewood.

As my mother poured out the troubles she had in the household she’d married into, O-Hatsu would go about her business as usual. With rationing in force, we rarely had any sugar. But she always had some on hand; a pinch of the precious stuff was dissolved in a cup of hot water and given to me to drink. Then she poured a cup of tea for my mother, and put out a variety of crunchy pickles and sweet miso for us to have with our hot drinks.

My mother would thank her tearfully before going on with her story, without touching the tea. O-Hatsu listened sympathetically to her complaints, sometimes putting in comments like “You shouldn’t have swallowed all that. If it were me, I would’ve given them a piece of my mind.” Her tone was half scolding, half encouraging.

A good long cry seemed to help, and my mother would slowly calm down. O-Hatsu would then point to the tea and pickles, urging her to help herself. By the time she picked up the chopsticks, raising them with both hands briefly in thanks, and reached toward the plate, her cheeks were dry.

“Everything’s so tasty,” she’d say. Though she would start out reluctantly, it was hard not to enjoy these treats. At our house, we couldn’t manage to make that many kinds of pickled vegetables by then.

After a second cup of tea, it was time to go. My mother said her thanks where she sat, bowing deeply, both hands on the floor.

It would have been a little too obvious if she had come carrying an empty bamboo basket on her back, but that also meant that on our way home she had her hands full of potatoes, carrots, and other vegetables we’d been given, and it was my job to hold the lantern.

I remember another time when O-Hatsu looked her over and said, “Gracious. Have you looked at yourself in a mirror lately?”

My mother had been very fair-skinned, but working all day in the fields had turned her skin so dark and rough it might as well have been a man’s. But O-Hatsu’s comment apparently didn’t upset her—didn’t hurt her at all. She just smiled, looking a bit embarrassed.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A True Novel»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A True Novel» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A True Novel» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.