'We're Fighting Fathers!' the men all bellowed.

'And whadda we want?' Brooke called back.

'Justice now!' the men cried.

The atmosphere of resentful aggression in the room reminded Dave of sour-faced old cabbies moaning on in their shelters. The Fighting Fathers had the distorted mouths and clenched eyes of some bloody Muslim fanatics burning an American flag …

'Motivation is the key,' Brooke resumed, pacing the little podium. 'Without motivation we cannot hope to have any success with direct action, which is why I'm happy to welcome here this evening a motivational speaker who's going to give it to you straight concerning the Judaeo-Feminist forces lined up against us.' Judaeo-Feminist? 'He runs his own, hugely successful data-retrieval business, Transform Services.' Transform Services? 'He's a leading light in our brother organization, the Stormfront Nationalist Community. Will you give a big dads' welcome please to Barry Higginbottom!'

A man dramatically bashed open the swing doors and stood in the characterless strip lighting of the Trophy Room. It was the Skip Tracer — and the sweat was lashing off him.

'A book, you say?' Anthony Bohm looked at the cabbie through the thick, round lenses of his vintage, wire-rimmed spectacles. When a young man, Bohm had affected the glasses as a badge of maturity — the lenses had been of clear glass. However, with an irony that was not lost on him, as Bohm's career had progressed, so his eyesight had satisfactorily deteriorated, until he acquired the searching gravitas of the genuinely myopic.

'That's right, a book.' Dave looked around at the gloomy room, which was dominated by an enormous duct running across the ceiling, the housing of which was covered by flaking tinfoil. A decade-old flyer hung from bashed chipboard by yellowing tape, proclaiming DON'T DIE OF IGNORANCE. The room was somewhere deep in the basement of St Mungo's, a rundown hospital off the Tottenham Court Road.

This wasn't his and Bohm's first session together — they'd had one up at the Halliwick in Friern Barnet, another down at King's on Denmark Hill. Bohm told Dave that he was seeing him 'on an unofficial basis, it's very much a personal thing between me and Zack Busner', and as the psychiatrist took a series of locum positions around the city, his patient was required to follow. This was no hardship for Dave, who had resumed cabbing as gently as possible, only going out for a couple of hours during the off-peak. He used his weekly sessions as a low-anxiety conduit, picking up fares along the way as he wended to the next rendezvous with the mobile shrink.

'When I was … well, y'know, Tone, when I'd lost it,' Dave said, 'I thought there was this book inside me, this book I'd written … but now I dunno — I dunno.'

'We've talked about your childhood,' Bohm continued, 'your relationships, your work. I like to think we've built up some trust between us.' He smiled, and his white goatee flicked like a hairy digit. Dave smiled too — anyone with such preposterous facial hair could hardly be malevolent. 'When Doctor, ah, Fanning, prescribed Seroxat for you in 2001 I'm sure he did what he felt was the right thing. However, the facts are that a small minority of patients have bad reactions to the drug — psychoses even. Your book dates from this period. If we can somehow dig it up from your unconscious and, so to speak, read it together, I think it would resolve a lot of your issues.'

Each of these measured remarks had been ticked off by Bohm, one plump finger pulling back the others. He now held the annotated hand aloft. 'Goodbye until next week,' he said, 'when we'll be meeting' — he consulted a fat little Filofax opened on his hefty thigh — 'at the Bethesda in Bermondsey.'

Dig up the book. Dig it up — search for it in the scrubby desert of his own mind. On the poxy little colour telly in the corner of his room, Dave Rudman saw clip after clip, all featuring the same stock characters: UN Inspectors in short-sleeved shirts and sweat-soaked jackets; Baathist apparatchiks in tan fatigues; to one side a gnarled old Bedouin in a dirty white cloakyfing. Behind them, on a plain of gravel that faded to a wavering horizon, stood corrugated-iron sheds and hunks of industrial equipment — hoppers, conveyor belts, ducts — all of them streaked with rust and dust. A mechanical digger petted some sand, arid wind plucked at the corners of the Inspectors' clipboards, riffling the computer printouts. Hard to think of them manufacturing anything there. . Don't look like they could turn out a bloody widget, let alone nuclear-bloody-weapons … Yet Dave could see, in this taut confrontation, a sinister evocation of his own troubled life. Buried inside me … all that sickening guff … poisonous thoughts. . got to dig it up …

What was he doing with Phyllis? Not that they'd actually done anything together. A couple of cuddles on the duffed-up sofa in Dave's flat, a chaste kiss on parting — no tongues. Phyllis wouldn't even invite him out to her place, which was in the sticks, out by Ongar … off the edge of the world … Instead she saw him in Gospel Oak, after visits to Steve in the hospital. Or else Dave drove into town and ranked up in Bow Street. Phyllis worked in Choufleur, a vegetarian restaurant on Russell Street, and, despite the fact that she looked even freakier in her voluminous smock and blue-striped apron, a mushroom-cloud hat perched on her curls, Dave couldn't help but recognize the feeling in his chest when she came out from the back entrance to share a B & H with him by the bins as one of affection, that's it… affection. .

Slowly, methodically, Phyllis invested what spare affection she had in pushing the cabbie back into the mainstream of life. She persuaded him to contact Cohen, his ex-lawyer, and to begin to probe out the situation with Carl. She helped him to amalgamate his debts, and by taking a new mortgage on the little flat get enough money to start repaying them. Together they wrote letters to the County Court, asking for fresh reports, suggesting that his mental breakdown be taken into consideration. They paid off his arrears and then appealed to the Child Support Agency for a reduction in payments. Then they picked up his paper trail, finding anomalous things, like a bill from a Colindale printer for £9,750. It was dated December of the previous year and had been paid. Along the bottom was stamped: RUSH JOB.

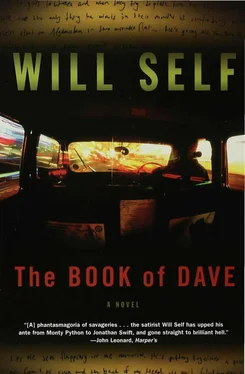

The year whimpered to its end. One day Dave Rudman was by the lights at the top of Lower Regent Street. Limos stretched out beside the Fairway while buses bent around it. First Dave stared at a man holding a sign for a GIANT GOLF SALE. Then he looked at a souvenir stall flogging miniature cabs with Union Jack decals, figurines of tit-headed coppers and tiny red model phone boxes … toyist crap. Finally, he peered up through the windscreen of the Fairway at the huge electronic signboards covering the buildings of Piccadilly Circus. One showed the Circus itself — the teeming crowds, the enmeshed traffic. Then, without warning, water began to flood between the buildings, a tidal bore that came surging along the rivers of light. Dave was shocked — what could this apocalyptic vision be selling? Then the flooded concourse wavered, fragmented and was replaced by a slogan: DASANI MINERAL WATER, A NEW WAVE is COMING.

'Excuse me? Excuse me?' The fare was an elderly priest and he wanted to go to Mill Hill. 'St Joseph's College, d'you know it?' Dave did. Who could miss it, with its strange painted bust of Thomas More out front, flesh tones as realistic as those of a showroom dummy? The fare was ill disposed to chat — and that suited Dave fine. He drove up the long, straight thoroughfare from Marble Arch. Then, as the cab passed through Kilburn and Cricklewood, then over the North Circular to Colindale, it began to come back to him. Dropping off the fare at the College, he made change in a cursory fashion, unconcerned by the nugatory tip. Dave drove along the Ridgeway to the Institute and, parking up, retraced his footsteps of the previous year.

Читать дальше