Dave Rudman waited and waited. He quit his seat only for tea and piss. He filled in the gaps by scanning over and over the same copy of Take a Break: 'Sharon Finds a Lump', 'Don't Snip it, Dave', 'Lonely Dad's Last Text — Without Them I am Nothing'. He was the subject of scribbled notes passed from receptionist to receptionist, secretary to secretary. He sat among the victims of street fighting and the casualties of domestic warfare. Patients waiting in queer déshabillé for transport to other hospitals were still more refugees, in their outdoor shoes and bathrobes, their raincoats and nighties.

Late on the following day, when he'd been waiting for nearly fourteen hours, Dave Rudman was summoned to the eighth floor and, accompanied by an orderly, rode the lift up. Insanity stank out the confined space like an eggy fart. There was a bird-beaked woman with a pot plant; a limp technician carrying a tray silently chattering with plaster casts of teeth; a yellow-faced girl in a yellow dress eating a yellow aerated cream dessert in a yellow plastic pot — but the stench came from the cabbie.

Even so, Dave wouldn't have been admitted if he hadn't attacked the orderly and clumsily tried to throttle him outside the door of Jane Bernal's office. She stepped out into the pedestrian horror of it: one big white man trying to bang the head of a small Asian one against an institutional wall. 'You fucking terrorist!' Rudman was screaming. 'You wanna cut my fucking head off or what!' A framed watercolour of Betws-y-Coed, allocated by a distant committee, rattled on the brickwork, then fell and shattered at their feet.

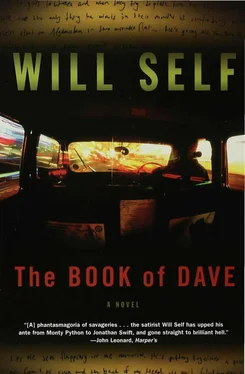

Had Dave Rudman been in any state to appreciate it, he would have. Would, perhaps, have been pleased by the whirl of activity his breakdown generated. After thirty milligrams of Chlorpromazine he was lucid enough to give up his keys, his address, Gary Finch's and his parents' phone numbers. A psychiatric social worker was assigned, calls were made, pill pots were collected from the flat in Agincourt Road. A pathetic flight bag was brought up to where cabbie 47304 was ranked up for the next seventy-two hours. Jane Bernal interviewed him, a standard risk assessment: reality testing, cognitive function, a physical once-over that had the functionality of a car service. The gash on his head was sponged and taped by a nurse. But Rudman wasn't interested in any of it; he only wanted to tell her about –

'A book, he says he's written a book.'

'Hmm.' Dr Zack Busner stood by the window in his office, which faced out over the Heath. Gulls were riding the thermals over Whitestone Pond. What is it with these seafowl? he wondered. Have they come inland because they anticipate a deluge? Should we get Maintenance to start building an ark? 'What sort of book is it, a novel?' He wasn't really concentrating on the conversation, rather trying to dangle a paperclip from the snub nose of an Arawak Indian head carved from pumice, which had been given to him by a grateful Antiguan student. He succeeded for a split-second, then the clip fell, tinkling, into the ventilation duct. 'Damn!' Busner turned from the window.

'No.' Bernal was patient; her colleague was showing his age. The breakup of his second marriage, the suicide of Dr Mukti, his young protege at St Mungo's — all of it had taken its toll. Looking at Busner's snowy cap of wayward hair and his deeply creased, amphibian features, Jane Bernal could see that he was shooting fast down the senescent rapids. 'It's a revelatory text.'

'Did God tell him to write it — or gods?'

'No, just the one god — except he isn't called that.'

'What's he called, then?' Busner turned from the window and smiled at Jane. She saw she had his attention; as ever her oblique way of introducing a case had drawn him in. 'Dave.'

'No,' Zack laughed. 'Not the patient — the god.'

'Dave, Dave too. Dave — the patient that is — is a taxi driver, and Dave — the god that is — has revealed this text to him. Do you know what the Knowledge is?'

'The Knowledge?'

'It's the encyclopaedic grasp on London streets that a licensed cab driver has to have.'

'So is that it?' Busner plodded to his desk and immured himself behind a pile of buff folders. 'Is that the revelation?'

'In part. My patient, Dave Rudman, says that the 320 routes that make up the Knowledge are a plan for a future London. Between them and the points of interest at each starting point and destination they make a comprehensive verbal map of the city.'

'A city of god … or Dave.'

'That's right, a city of Dave, New London.'

'Where is this text?' Busner asked. 'Can I have a look at it?'

'Well.' Jane Bernal drew a chair up to the desk and sat down. 'I don't believe this man literally transcribed his delusion, I believe he committed it to his memory. As you may be aware, brain scans have confirmed that the posterior hippocampus in London cabbies can be considerably enlarged — that's where the book is buried, and there's more to it than just his Knowledge, there's a set of doctrines and covenants as well.'

'That sounds familiar.'

'It is: it's the title of one of the Mormon holy books.'

'Is he a Mormon, then?'

'No, I don't think he's anything much,' Jane sighed, 'except a very ill man.'

'So what are Dave's doctrines and covenants?' As Bernal succumbed to melancholy, Busner became increasingly jolly — nothing pleased him more than a complex delusional apparatus.

'Oh, you know, the usual stuff, how the community should live righteously, the rules for marriage, birth, death, procreation. It's a bundle of proscriptions and injunctions that seem to be derived from the working life of London cabbies, a cock-eyed grasp on a melange of fundamentalism, but mostly from Rudman's own vindictive misogynism.'

'Vindictive?'

'He's separated from his wife, there's a court order restraining him from seeing his fourteen-year-old son. He's been mixed up with one of those militant fathers' groups. It's all very … distressing.'

'Hmm, I see, and his family — does he have any?'

'There are elderly parents living in East Finchley. I've interviewed the mother: she's long since withdrawn from him emotionally, seems traumatized. There's a brother in and out of hospital up in Wales, drug psychosis.'

'The father?'

'Alcoholic.'

'I see.' Busner picked up the Arawak head and began throwing it up in the air and catching it, as if it were an ethnic tennis ball. 'Of course, in the good old days we could have blamed the parents, but now we can go searching for pills to fit the pathology, or a pathology that fits the pills — there are pills, I presume?' Bernal consulted her file. 'Oh, yes, GP called Fanning. Usual story, began him on Seroxat, Rudman had a psychotic episode, Fanning gave him Carbamazepine to buffer it and Zopiclone for the insomnia. Rudman had another episode and Fanning took him off Seroxat and put him on Dutonin.'

'Ah! Someone's been on a few little junkets to Barcelona courtesy of Big Pharma. So, we take him off all of this and see what's what. And what is what in your opinion, Jane? Schizoid? Borderline? Both?'

'Almost certainly, but the funny thing is — well, the two funny things are — he picked me up late last year at Heathrow in his cab. I was on my way from Canada where I'd been visiting … my friend. I thought he was ill at the time, although I couldn't imagine how he was managing to drive a cab if he was schizoid. And then there's his delusion, it's complex, it's durable, but, if you set it to one side, Rudman is altogether lucid. I only got him sectioned because he tried to beat up Raj. He says the book is addressed to his son, that Dave — his god, that is — told him to write it for his son. I think he'd benefit — if you're amenable — from some chats with you.'

Читать дальше