‘The important thing to grasp, yeah?’ Gloria hectored Tom as Prentice pulled up behind the pick-up. ‘Is that these people have never been subjugated, right? They live now as they always have, beautifully and harmoniously. Respect their harmony — and they’ll respect you.’

If the copywriter’s screed on the bottle of Lake Mulgrene mineral water had been hyperbole, then so was the term ‘settlement’ when applied to the Entreati camp. It was a dump. Fifty or sixty men, women and children grovelled in the dirt, dragging themselves from beneath corrugated-iron sheets that had been laid over pits to sit chewing engwegge around smoky fires.

Then there were the dogs: slinking, squirming, yapping curs. There were chunks missing out of their mangy fur, their tails were twisted, their legs seized up. It struck Tom how few dogs he had seen — either over here or back on the coast. The dogs smelled, and they came dallying in — canine flies — to thrust their proboscises against his bare legs.

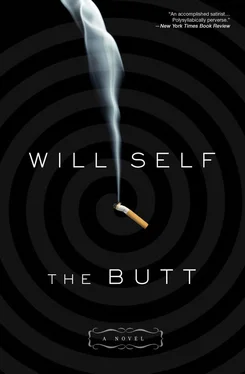

At the first moist contact, Tom’s own nose unblocked and a crowd of stenches — human and animal waste, rotting meat, wood smoke, singed hair, gasoline fumes — jostled for admission. Smell, the most ancient and canny of the senses. Apart from the very strongest, the most rank of odours, he had for a long time now been smell-blind, the white lines of his cigarettes blocking them out indiscriminately. Tom’s nose backtracked along Route 1, sniffing sweat, perfume, eucalyptus tang and foody bouquet. Back and back to Vance, where Tom had snuffled in the hollow of one of his twin’s neck, unaware that it — and he — were both redolent of ashtray.

In the midden the Entreati tenanted, shit, trash and broken glass were scattered everywhere. The pot-bellied children’s eyes were filled with pus from untreated trachoma, while fully a third of the adults were completely blind. All of them, except for the active young men, had streptococcal infections. Tom also saw the spavined legs of rickets sufferers, and heard the popping wheeze of tuberculosis.

Shortly before they had arrived a dead auraca had been thrown on a fire. It lay there, its coat smouldering, with a startled expression on its lama-like features. ‘It’s a great honour,’ Gloria explained. ‘They’re welcoming us to their cosmos, right?’

She seemed not to notice the disease, the malnutrition, the trash or the dogs. She strode from one humpy to the next in her black robes, a ministering nun handing out cartons of cigarettes and packets of bubble gum.

Soon, everyone over the age of seven was holding a fat packet of Reds and puffing away — some, preposterously, on more than one cigarette at a time. Meanwhile, the little kids blew blue bubbles that burst on their pinched black faces. Soon the dump became yet more littered, with butts and the slick films of the cellophane wrappers.

One thing that wasn’t hyperbole was Gloria’s estimation of their welcome. The Entreati were warm towards them, effusively so. Tom sat by the fire, torn between shame and disgust, as toothless old men and leprous children embraced him with their diseases. At last he managed to drag himself away and set off towards the unearthly limelight that played about the lake shore.

‘Don’t even touch the water,’ Gloria called after him.

Night was encroaching. Away to the east, back in the direction of Route 1, enormous crescent-shaped dunes marched along the horizon, each like the cast of a giant worm that was boring beneath the sands. The wind was soughing in off the lake, laden with mephitic fumes. There could be no question of even attempting to dabble in its celebrated waters, for the shoreline consisted of hundreds of yards of crusted salt and cracked mud. Oily fluid oozed between these platelets, streaking them cobalt, viridian and carmine — colours that belonged in a nail parlour, not the natural world.

As the last rays of the setting sun fingered the limpid surface of the immense depression, they caught on strange-looking rafts of some bubbly excrescence — like enormous frogspawn — that were floating perhaps a mile offshore.

Tom stood, swaying slightly, staring out over this desolate scene. After a while he realized he was not alone. One of the young Entreati men from the checkpoint had followed him down, and stood a way off, smoking, and apparently lost in his own thoughts.

Tom approached him: ‘Do you — can you speak—?’

‘English, mate? Yairs, ’course I bloody can. Did elementary in Trangaden — we all have, right.’

The Entreati was younger than Tom had supposed — little more than a boy, despite his height. Although he had directly contradicted Gloria’s insistence on the cultural isolation of the tribe, it wasn’t this that Tom wished to pursue.

‘Those’ — he pointed — ‘um, like, rafts out there — d’you know what they are?’

The Entreati lad laughed bitterly. ‘Them? They’re corpses, mate, big bloody mobs of corpses.’

‘Corpses? Have they been there long, I mean, shouldn’t you. .’

‘Some of ’em’, the lad said philosophically, ‘must be bloody historic — they’ve been out there all my life. See, here’s how it is,’ he went on, becoming animated. ‘When a bloke gets karked up in the Tontines, they dump his body in a wadi. Come the rains, they get washed down here, yeah. But the water in the lake — well, you can see what it’s like. It doesn’t matter if the bodies are rotting when they’re chucked in, yeah, when they get to Mulgrene they’re pickled for-bloody-ever.

‘Weird thing is’ — the young man poked meditatively at the crusted salt with the barrel of his gun — ‘the way they cluster together like that into those rafts. There’s no current out there, but they still do it. Bloody big bunk-ups — it’s like they’re keeping each other company, yeah.’

When they returned to camp the auraca had been buried in the ground and the fire raked over it, then built up.

‘It’s a traditional earth oven,’ Prentice told him.

‘Where do they get the fuel?’ Tom asked.

‘There’s mulga scrub south of here, apparently. Devilish stuff when it’s living — burns like billy-o once it’s dead.’

There was a bustling purposiveness about Prentice as he unloaded the SUV, taking three fat canvas bundles down from the roof-rack. Tom rubbed his sore eyes — he hadn’t noticed them before.

‘Got these in the Tontines, together with the other gear,’ the newly Swift One said, unrolling one of these. ‘Swags — you can’t sleep out in the desert without one.’

He left off his preparations and took a sheaf of receipts and bills from his jeans pocket. ‘The swags, a water bag, emergency flares, medical kit, gifts for the native mobs — it’s all here. I’ve added it up, old chap, and here’s the balance of what I owe you in cash.’ He gave Tom an affable smile and passed the money and papers over. ‘Thanks for the loans; we should be even now.’

Tom spyed another difference in Prentice as the other man readied the swags. He looked leaner and more ascetic — altogether less ridiculous. Then it struck Tom what it was: ‘Prentice — Brian. You’ve — you’ve. .’ he tailed off, stupidly embarrassed.

‘It’s my thatch, isn’t it, old chap?’ Prentice patted his bare forehead. ‘Ye-es, I shaved that daft fringe off — dunno why I hung on to it for so long.’ He laughed. ‘Nostalgia, I suppose. Better to face up to the fact that I’m going bald. It’s most peculiar. .’ He tilted his face up and his clear complexion glowed in the firelight. ‘I don’t think I could’ve, y’know, accepted that, without coming out here and being with the bing. . with these people.’

He stopped, clearly feeling that he had said rather too much, and busied himself with setting up their little subcamp for the night.

Читать дальше