A perfect little Hilton emerged from the orangey gloom. It was exact in every way, from its pseudo-Hellenic portico to its ornamental ponds dappled with water lilies, but maybe one fifth the size of any other Hilton Tom had ever seen.

And there, standing by the main doors, apparently forewarned of their arrival, a swirl of black-winged moths fluttering round his fastidious form, stood Adams, the Honorary Consul. While beside him was the morphed version of Tom’s own wife: Gloria Swai-Phillips, wearing a floral-print cotton dress.

The following morning, Tom had just returned from the concession stand and was at the sink in the bathroom, applying arnica ointment to his cheek — which had been badly bruised by the rifle’s recoil — when there was a knock on the door.

He admitted Adams, who walked past him and crossed at once to the far side of the room. Tom moved his discarded clothes from the easy-chair to the floor and invited the Consul to sit.

‘Good trip?’ Adams asked, crossing one thin shank over the other. He wore his habitual tan seersucker suit, and Tom was underwhelmed by the clocks on his red socks.

‘Don’t be facetious,’ Tom replied, and, heading back to the bathroom, called over his shoulder, ‘How the hell did you get here?’

Adams took a while answering. Then Tom heard the flat chink of hotel china and the bubbling of the dwarf kettle. Adams was making himself a cup of Nescafé. Tom concentrated on flossing his teeth, then pulling the hairs from his nostrils with a pair of tweezers. The sharp little twinges were reminders: You’re here! You’re here!

Eventually, he heard a slurping intake, followed by: ‘Don’t get snippy with me.’

‘I’m sorry?’ Tom went back into the bedroom. Adams was bent over the three-panelled mirror on the vanity table, examining the back of his head. He looked round. ‘I said, don’t get snippy with me. I’ve had a, ah, hard-enough morning already.’

The Consul set his coffee cup down on the carpet and peered at Tom through his increasingly pellucid spectacles. Clearly, like a batty old hypochondriac, he was soliciting sympathy.

Tom obliged. ‘Oh, why’s that?’

‘Fellow countryman of ours called Weiss — he was caught smoking in the john of a flight coming into Amherst—’

‘My, my. That does sound serious.’

‘Serious enough.’ Adams glared at him with eyes now entirely visible. ‘He’s doing ninety days at Kellippi, and even after a month he’s not in very good, ah, shape.

‘Have you ever seen a bauxite mine, Brodzinski? The convicts get the worst jobs. It’s very brutal, ah, extraction — huge machines, a lot of highly toxic dust. The Belgian outfit that operates the mine isn’t overly concerned with safety, given that the workforce consists of convict labour, native, desperate, or all three.’

‘What’re you trying to say, Adams? That I’ve gotten off lightly? And anyway’ — Tom sat down opposite him on the end of the bed — ‘how did you get here?’

The Consul took another slurp of his Nescafé before answering. ‘Miss Swai-Phillips and I flew to Amherst, then drove along Route 2. The mine people did offer us a light aircraft, but, as I’m sure you, ah, appreciate, I have to keep my distance. .’

He fell silent. He was staring past Tom’s shoulder — not at the Andrew Wyeth reproduction that hung above the bed, but the fifth of whisky that stood, half empty, on the beside table.

‘I kinduv assumed your, uh, jurisdiction wouldn’t extend this far,’ Tom said. He was trying deliberately to nettle the Consul. ‘I mean, isn’t this the Western Province?’

Adams was unperturbed. ‘Yes, but I’m a servant not of the national government, Brodzinski, but of our own. It’s in that capacity that I’ve driven another thousand kilometres through the Tontines to come and, ah, liaise with you.’

‘I’m not sure who it is you goddam serve, Adams,’ Tom said bemusedly. ‘But tell me this much: if you could fly clear across to Amherst, then drive only a thousand klicks — why the hell did I have to come overland for three and a half, nearly getting my goddamn ass shot to pieces in the process?’

‘I can see you’re upset,’ Adams said, and Tom had the gnawing insight that this was all diplomacy ever consisted of: the understatement of the obvious. ‘Have you spoken to your family yet? You’ll find that you can dial them direct from here without the country code — a little, ah, quirk of the Tontine Governmental Sector.’

He stood up and set his stained cup down on the vanity table. ‘Paradoxically,’ he added, ‘if you want to phone someone in the actual Tontines, it’s an international call.’

‘What about Gloria?’ Tom had meant to say ‘Martha’ — the two women were, once again, confused in his mind.

‘I’m sorry?’ Adams fastidiously detached Tom’s hand from his arm — a hand Tom hadn’t been aware of laying on him.

‘W-What’s she doing here?’

‘I thought Miss Swai-Phillips explained that to you back in Vance? She’s responsible for running orphanages here in the Tontines; she’s a well-respected charity worker and philanthropist. I believe her charity is holding a function this evening, here in the hotel. No doubt you can be invited if you’d like to find out more.’

Adams was making for the door when Tom had a sudden intuition: ‘That’s bullshit, Winnie.’ He hadn’t used this intimacy since the night they had eaten the binturang together at Adams’s house. It pulled the Consul up short, and, when he turned, Tom saw he had lost some of his aloofness. ‘It’s to do with Prentice, isn’t it? It’s to do with. . his. . With what he did. I mean, she looks after kids — and he. .’ Tom left the insinuation hanging there: an ugly odour that the hotel’s aircon’ could never dispel.

Adams’s voice softened. ‘You know perfectly well that I can’t discuss that with you, Tom.’

‘But you’re not denying it, are you? Those drugs — the baby stuff, it’s for her orphanages, isn’t it? Jesus! I dunno what’s worse, carrying the can for my own dumb mistakes or chauffeuring that sicko.’

‘As I understand it, Tom, you have every reason to be grateful to Brian Prentice. Mrs Hufferman told me that whole story yesterday evening. I believe the technical term for what he did’ — the Consul’s long face warped into sarcasm — ‘is saving your life.’

Tom stood, cowed, as Adams reached for the door handle. Then the Consul detonated one of his deadpan devices: ‘Incidentally, Brodzinski, I think you should know this. Shortly before I left Vance I had a call from the DA’s office. Mrs Lincoln has instructed the medical staff at Vance Hospital not to resuscitate her husband if he should have a, ah, crisis. Bluntly, this means you probably haven’t got long to get down to Ralladayo and make your reparations. As I’m sure Jethro Swai-Phillips explained, all bets are off if this becomes a capital offence.’

With that, he quit the room.

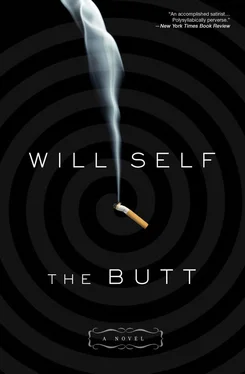

Tom found Prentice smoking behind the Hilton parking lot. The sixth sense by which the local smokers always knew exactly where the sixteen-metre demarcation line ran never failed to amaze Tom. There were so many public buildings clustered in the TGS that the intersection of several lines allowed smokers only a small curvilinear plot, within which to stand, sucking and blowing.

Clustered with Prentice were seven other Anglos. Their short-pants suits, pressed shirts and flamboyant ties gave them the look of insurance salesmen — which is precisely what they were. It was tragicomic the way these men were compelled to stand, shoulder to shoulder, steeped in their own fumes, while on all sides there was the cool play of sprinkler systems on beautifully manicured lawns.

Читать дальше