Still, on this particular dark day, full as it is with harbingers of mortality, the obsidian bulk of the John Hancock Center looks altogether threatening, as does the clanking lift lobby. Some of the lifts are out of order and shrouds of plastic have been taped across the entrances to these steely tombs. On the long ride up we stand together with a bog-ordinary quartet of out-of-towners — regulation moustaches, baseball caps, cameras and avoirdupois — and I wonder at their sang-froid. Could these couples be disciples of Epicetus, who’ve undertaken this purgatorial sightseeing purely in order to cultivate stoic detachment? Or are they merely dumb hicks?

Up on the observation deck we can feel the whole mass of steel, concrete, stone, plastic, fibre-optic cable and nylon carpet heal beneath us, as if it were a tall ship about to tack off across the crumpled grey surface of the lake, which curves away to the horizon. Like Prometheus I’m bound to this rock while the eagles of anxiety gnaw at my liver. The boy has no such problem. He scoots about from info point to info point; for him it’s enough to be here now. There’s a place where you can go out on to an enclosed terrace and promenade in the screeching elements, so naturally I force him to do the walk. Now it’s his turn to feel fear — and mine to experience catharsis. It occurs to me that terrorism is Schadenfreude taken to the point of evil.

In the winter of 2001, my friend John and I were in Konya, central Anatolia, to attend the Mevlevi Festival where the dervishes famously whirl. There had been much derision concerning the festival in the tourist literature we’d read. Apparently the ‘dervishes’ weren’t the real, impoverished, Sufi thing, but mere hirelings. It was true that the gig was held in a basketball stadium and appeared to be sponsored by a Turkish washing-machine company called Arçelik, but for all that the whirling quite spun us out. There was this, and there was the general austerity of cold-comfort Konya, a city of half a million-odd souls in the grip of Ramadan, as literally dry and dusty as it was metaphorically dry. John, having downed the sole can of beer provided in his minibar within an hour of arrival, tiptoed softly along the corridor to tap on my door and cop mine.

One evening we were sitting in the lobby of our hotel, the Balikcilar, a heavy joint — all shiny marble and knobbly stonework — when the divan we were sitting on was kicked by the gods from beneath. It felt as if this chunky leatherette banquette had transmogrified into a waterbed. The quake lasted for about a minute, then the lobby emptied in seconds — this was a region where people knew about earthquakes — and John and I found ourselves standing on a roundabout idly contemplating a bizarre bed of decorative cabbages.

At the time the tremor failed to impinge. After all, we’d been in the grip of vicarious religious fervour ever since arriving in Turkey. It wasn’t until the following evening, after a three-hundred-kilometre drive into Cappadocia, when we saw on the BBC World Service that the earthquake had felled a minaret back in Konya and killed six people. I now found myself in the bizarre position of having escaped death in a natural disaster, only to be informed of the fact by people a thousand miles away in the Aldwych.

But, anyway, Cappadocia itself was also bizarre. This was an unleavened landscape that looked as if it had been crumbled and then kneaded by history itself. Up here on the high Anatolian plateau troglodytes had been tunnelling into the ground for millennia: there were meant to be whole cities constructed souterrain, in which the natives had waited out the depredations of whichever invading army — Greeks, Romans, Persians, Ottomans — happened to be marching through at the time. Perhaps, I mused, it was one such legion of transients, cleverly tricked into tramping along a handy fissure, whose ghosts were now perturbing the earth?

Central Turkey had the look of antiquity about it. Even the modern settlements had the appearance of rime, as if their substance had crystallised out of the crust they stood on. Yet as subsequent earthquakes in Ankara and along the shores of the Black Sea would so disastrously confirm, contemporary Turkey was a society whose urbanity was constructed out of dangerously substandard concrete; powdery, friable stuff, readily pulverised by the slightest shake. Personally, I blamed the oblong shape of the country. After Nepal, Turkey is the most oblong country I’ve ever visited, but a glance at any reasonably good map will soon tell you that oblong countries have a high incidence of natural disasters and usually fairly grim human rights records as well.

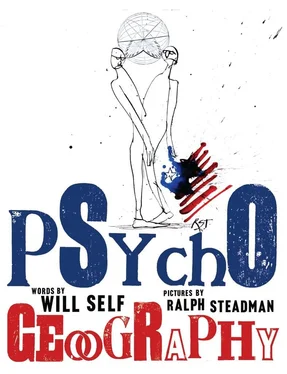

Chile, Israel, Togo, Portugal. . this list is by no means exhaustive — or even fair — but when it comes to whacko theories there’s no reason why psychogeographers can’t get in on the act. Anyway, to get back to Cappadocia, it had been a gruelling day’s drive. As we’d ascended the plateau from Konya in our rental Fiat, I’d begun to notice a peculiar, prismatic distortion beginning in my left eye, which then spread gradually to the right. It was as if some sadistic ocular surgeon had inserted a prism into my retina, which was refracting the harsh light into swirling, kaleidoscopic patterns. I couldn’t bear to tell John about it, because he might insist on driving. I don’t do passenger.

There was this, and there was also the knowledge that this wasn’t the first time I’d experienced the distortion. In fact, it had happened a couple of times before when I’d been climbing Scottish mountains. I’d be fine up to 3,000 feet, and then bingo! my eyes would turn into children’s toys. Within hours of my descent a kind of clarity would return. Sitting that night in the lobby of our troglodyte hotel, watching the earthshaking news from Bush House, it impinged on me that perhaps my eye problem was also an act of God. God wanted me to stay down, or even go lower; that way I wouldn’t escape the retributive ruckling of his premier creation.

São Paulo was — to adopt an idiom — way too much. The ride in from the airport through asteroid belt of the favelas , and then the planetary scale of the urban mass itself. Sitting in a restaurant atop the highest building in the city, I could see what looked like a snaggle of teeth on the horizon some twenty miles away, but when I scrutinised them carefully I saw that they too were equally vast edifices. The comprehension gap was as disorienting as the culture shock. In my four-star hotel I couldn’t find one staff member who spoke more than rudimentary English or French; if you wanted to get anywhere here you needed Portuguese or German.

I couldn’t get my plastic to work in the cash machines, so one afternoon I set out to find a bank where I could draw some money. I walked and I walked. As well as being illimitable São Paulo seemed to have little or no comprehensible street plan. It was like an unholy miscegenation between London and Los Angeles: mighty metropolises, grey and golden and exhaust-stained, humping at the place of dead roads. In some dusty square, metal-tortured boulevard or another, I fell in with an elderly German who spoke sinisterly good English. I say sinisterly because everything about him was sinister to my paranoiac mind. What was he doing here? Why did he talk about himself so circumspectly, but want to know all about me? I could almost visualise the death’s head badges of the SS on his faded Hawaiian shirt.

The minibar in the hotel was no help. It was called the Selfbar — so I took it personally and downed the lot: the scotches, the vodkas, the gins and the Amazonian armpit aguardientes. Then I howled down the lift shaft. My Brazilian translator, the redoubtable Hamilton dos Santos, seeing the state I was getting into, suggested a little R&R in Rio. I flew there on a Varig flight for which there was no internal security. This was ten years ago, and perhaps things have changed since, but in those days the explanation Brazilians gave me for the lack of metal detectors at their airports was that everyone insisted on packing guns.

Читать дальше