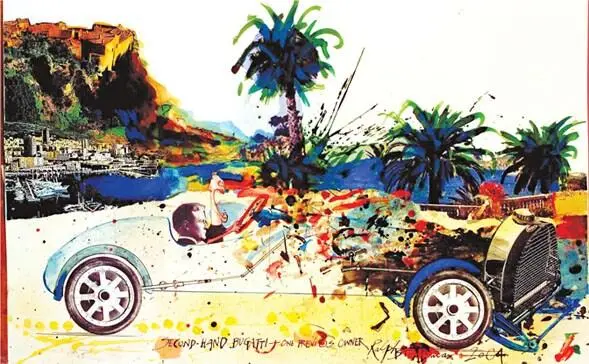

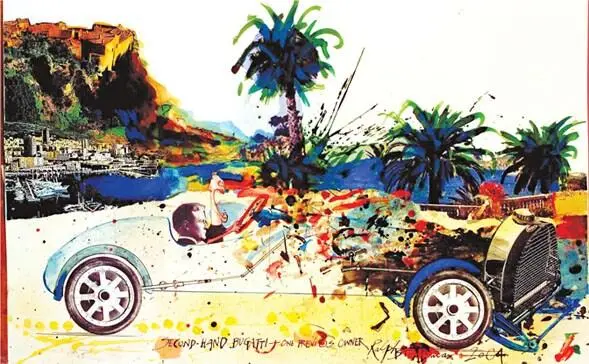

Like all exotica experienced in earliest childhood, the South of France became entangled in my mind with its representations. Was it Willie Maugham who entertained at Cap Ferrat — or me? Was it Scott and Zelda who wheeled their Bugatti along the Corniche — or me? The swaddled figure scratching away in his notebook on the beach at Bandol, was it Thomas Mann, or, yet again, me? Hemingway and Picasso fighting on a canvas ring in the market square of Juan-les-Pins (where my lovely goes to, tra-la-la-la-la-la-la!); Truffaut and Bardot sunning themselves on Ari’s yacht; Cézanne reducing the rocks to savage geometric configurations; Maigret nosing about Porquerolles savagely puffing on his pipe. Me, me, me, me-me-me!

So when I actually got to go there in early adulthood the experience remained curiously unreal, not least because I was under the auspices of louche Anglo-French aristos. We ate long lunches at restaurants in perfectly conical medieval hilltop villages, then drove to Les Calanques and dove off the white stone ledges into the inky Mediterranean. Or else we fetched up in Cassis, and after downing the requisite langouste quadrille, took the bizarre little mock submarine, which, semi-submersed, pedaloed across the harbour, affording us obscure views of the reefs of old Evian bottles on the seabed.

Bouillabaisse royaume was eaten at Le Brusc, in a giant glassed-in restaurant, itself not unlike a fish tank; and frankly the French bourgeoisie stuffing their faces were quite as ugly as the fish in the stew. There were promenades along the beachfront at Bandol, and on one memorable occasion we dropped acid and crossed over to the queer little island of Bendor. This blob of land was owned by a pastis millionaire and had been tricked out as a concrete Moorish fantasia, all crenellated courtyards and wonky minarets. In truth, Bendor was so bizarre that it quite neutralised the effect of the LSD; and it wasn’t until we were back in Bandol, at one of those café-bars that charges forty quid for a vitelline-hued cocktail in a glass the size of a vitrine, that I remembered I was hallucinating.

My friends knew the by then venerable Logical Positivist Freddie Ayer, who had a house in the vicinity, and he much impressed me by his remorselessly rational impression of the world. When asked what single thing reminded him most of Paris, he thought for a while before answering: ‘A road sign, with “Paris” written on it.’ I savoured this remark, and in a way it was one of the seeds that eventually grew into the gnarled tree of my own psychogeographic preoccupations.

But eventually strolls in pine-scented woods and thyme-reeking maquis palled. There just wasn’t the impetus required for even one more game of table football in the local bar. We were young, we had a sports car, we demanded bright lights and glittering debauchery. We decided to drive to Milan. We took off along the péage at 120 mph, whipping past Toulon, Hyères, St Tropez and Nice, before slowing to a crawl for the border crossing at Menton. Here, only yards before reaching Italy, we picked up a hitchhiker, a guileless local lad who’d just gone out for a stroll. Whipped up by our on-the-road fervour he determined to accompany us and drove us insane across northern Italy playing his guitar and singing old Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young songs.

On the way back the following night, pie-eyed by excess, we were pulled up before recrossing the border by one of those comic-operetta Italian policemen, all side-striped jodhpurs and a hat like a piece of shiny black leather origami. In those far-off pre-EU days papers were required, and, while we had ours, the poor strolling player had none, so without ceremony he was extracted from the jump seat and dragged away into custody. For some minutes we sat in the orange darkness and debated whether or not we should do something, but we were young and feckless and frightened, so we floored it and drove on. Besides, the whole trip had partaken of the dreamlike character of the Côte; and even now, more than twenty years later, I still find it hard to believe that the hitchhiker really existed at all.

In Chicago the boy wants to go up the Sears Tower. Of course, it’s a mere 110 storeys high, and has long since been eclipsed by other vast edifices in the Near and Far East, but, still, it’s there, we’re there, he wants to make the ascent. I don’t know exactly where these bigger buildings are, any more than I know precisely how high the Sears Tower is. Nevertheless, I picture these loftier skyscrapers as being shaped like colossal bodkins and darning mushrooms; crudely forceful examples of how reinforced steel and glass can be shaped to form the most prosaic of objects, then writ large, stupidly gross.

The Riyadh Bodkin and the Kuala Lumpur Mushroom are positive Meccas for all kinds of daredevils — of this much I’m sure. Decadent Saudi princes pilot microlights through huge holes in their façades, while Malaysian spider men scale them using giant suckers in lieu of crampons. All these activities serve to demonstrate is that modernist megaliths have completely suborned the role of natural features in providing us with the essential and vertiginous perspective we require to comprehend accurately our ant-like status. Natch.

My brother, who’s an eminent architectural historian, often observes that the highest building to be erected during any given economic cycle is invariably a harbinger of recession. One thinks of Canary Wharf before the downturn in Britain of the 1990s, or the Twin Towers in New York before the shit hit the fan in the early 1970s. Come to think of it (and I am thinking of it a lot as we glide up Wells Avenue, the gale off Lake Michigan turning our socks into windsocks), the terrorist attacks of 9/11 may well doubly confirm this thesis by actually inducing a recession. Like so much in this brave new century, the economic edifice theory seems like an example of over-determination: ‘too-true, too-true’, a wise owl might coo.

Yes, I’m thinking about it a lot because it’s only forty days since the WTC imploded, and the boy and I are adrift like autumn leaves in a chastened, muted America. I admire the way his youthful enthusiasm segues with his lack of neurotic superstition. Sadly, the management of the Sears Tower don’t see it that way and have closed the observation deck. The security men stare at us as if we’d asked to get on top of them — not just their building. But nevertheless they’re happy enough to direct us the blowy mile back over the Chicago River and down Michigan Avenue to the John Hancock Center, which — while only a mere ninety-odd storeys — is still open for business.

I went up the WTC in 1993; I’ve been up the Empire State as well. The Eiffel Tower hosted me when I was eleven — the same age as the boy. Indeed, I’ve usually scaled the highest building in any city I’ve visited. In the States it’s de rigueur for your hosts to whip you up one soon after your arrival, so that the descent into the airport followed by the ascent by lift feel curiously like the two sides of a rollercoaster’s parabola. Nonetheless, it isn’t the 1,000-footers that I find the most intimidating. Hedged round with their ordinary mystique — people work here for chrissakes! — they are also quite simply too high to provoke vertigo. Peering down from such a peak perspective only ever reduces the world below to an intelligible version of itself: the microcircuitry of society.

Читать дальше