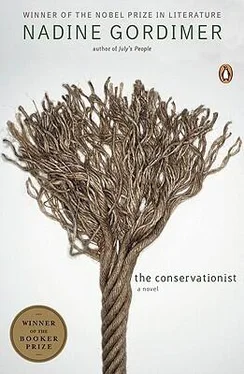

Nadine Gordimer - The Conservationist

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - The Conservationist» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1983, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Conservationist

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1983

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Conservationist: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Conservationist»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Conservationist — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Conservationist», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Outside the kitchen door he distends his nostrils distastefully at the smell of duckshit and three or four pallid kittens whose fur is thin as the bits of duckdown that roll softly about in invisible currents of air, run from the threatening column of his body. Psspsspss he calls, but they cower and one even hisses. He strides away, past the barn, the paddock where the cows about to calve stand hugely in company, and the tiny paddock, where the old bull, used less and less now, with the convenience of artificial insemination available, is always alone, and he continues by way of the mealie fields the long walk around the farm, on a perfect Sunday morning, he was about to begin when he drove down to the third pasture.

The matter of the guinea fowl eggs has not been settled. He’s conscious of this as he walks because he knows it’s no good allowing such things to pass. They must be dealt with. Eleven eggs. It would have been useless to put them under the Black Orpingtons; they must have been cold already. A red-legged partridge is taking a dust bath where it thinks it won’t be spied, at the end of a row of mealies reaped and ready to be uprooted. But there are no guinea fowl feeding down in the far field where they usually come. Those bloody dogs; their dogs have probably been killing them off all summer. Eleven freckled eggs, pointed, so different from hens’ eggs made to lie in the standard depressions of plastic trays, in dozens, subject to seasonal price-fluctuation. Soon there will be nothing left. No good thinking about it; put a stop to it. The hands of the child round the freckled eggs were the colour of the underside of an empty tortoiseshell held up to the light. The mealies are nearly all reaped, the stalks stooked in pyramids with dry plumy apexes, the leaves peeling tattered. Distance comes back with these reaped fields, the ploughed earth stretching away in fan-shaped ridges to its own horizon; the farm grows in size in winter, just as in summer as the mealies grow taller and thicker the horizon closes in, diminishes the farm until it is a series of corridors between walls of stiff green higher than his head. In a good year. If there is going to be a good year, again. A tandem harrow has been left out to rust (no rain, but still, the dew can be heavy). Now is the time to clear the canker weed that plagues this part of the field, near the eucalyptus trees which have made a remarkable recovery, he can scarcely notice, for new branches, the stumps where they were always chopping them for firewood until a few years ago.

Although he had no sign of it when he set out this morning, a Saturday night headache is now causing pressure on the bridge of his nose; closing his eyes against the light he pinches the bone there between thumb and finger. He feels pleasantly, specifically, thirsty for water. He makes for the windmill near an old stone outbuilding. The cement round the borehole installation is new and the blades of the windmill are still shiny. He puts his head sideways to the stiff tap and the water sizzles, neither warm nor cold, into his mouth. The windmill is not turning and he releases the chain and arm that brake it in order to set it going, but although it noses creakily, it does not begin to turn because there is no wind today, the air is still, it is a perfect autumn day. He sets the brake again carefully.

A little after one, passing the servant Alina’s room beside the fowl-run, on his way up to the house, he sees Jacobus talking to her. He and the herdsman do not seem to see each other because they have seen each other before and no greeting is exchanged. He calls out: — You’d better take something — to put over, down there. (His head jerks towards the river.) A tarpaulin. Or sacks. -

Mehring was not a farmer although there was farming blood somewhere, no doubt. Many well-off city men buy themselves farms at a certain stage in their careers — the losses are deductible from income tax and this fact coincides with something less tangible it’s understood they can now afford to indulge: a hankering to make contact with the land. It seems to be bred of making money in industry. And it is tacitly regarded as commendable, a sign of having remained fully human and capable of enjoying the simple things of life that poorer men can no longer afford. As the chairman of an investment fund, of which Mehring was a director, said — You get a hell of a kick out of a place like that, don’t you? I know that when I go off Friday afternoon and find a nice field of my hay being baled, I haven’t a worry in the world. Of course, if hail arrives and batters the young mealies, the end of the bloody world’s come — A special boyish grin reserved for the subject of farming showed how remote that disaster was from any reality that might originate in the boardroom in which they were chatting.

Mehring went to his farm almost every weekend. If he had put his mind to it and if he had had more time, he knew he could have made it pay, just the same as anything else. But then there would be an end to tax relief, anyway; it would be absurd. Yet land must not be misused or wasted and he had reclaimed these 400 acres of veld, fields and vlei that he had probably paid a bit too much for, a few years ago. It was weed-choked, neglected then (a dirty piece of land, agriculturally speaking), yet beautiful — someone who was with him the first time he went to look at it had said: — Why not just buy it and leave it as it is? —

He himself was not a sucker for city romanticism and he made sure the rot was stopped, the place cleaned up. A farm is not beautiful unless it is productive. Reasonable productivity prevailed; he had to keep half an eye (all he could spare) on everything, all the time, to achieve even that much, and of course he had made it his business to pick up a working knowledge of husbandry, animal and crop, so that he couldn’t easily be hoodwinked by his people there and could plan farming operations with some authority. It was amazing what you could learn if you were accustomed to digesting new facts and coping with new situations, as one had to do in industry. And as in the city, you made use of other people — the farmers round about were professionals: — I’m not proud, I’ll go over and sit on the stoep and pick their Boer brains if I need to. -

He took friends to the farm sometimes at weekends. They said what a marvellous idea, we adore to get out, get away, and — when they debouched from their cars (the children who opened the gate at the third pasture the richer by a windfall of cents) — how lovely, how lucky, how sensible to have a place like this to get away to. There would be a sheep roasted on a spit rigged up over the pit and turned by one of the boys from the compound, and bales of hay to sit on, lugged down on instructions over the phone to Jacobus. The wine was secured to keep cool in the river among the reeds at the guests’ backs and the picnic spot was carefully chosen to give the best view of the Katbosrand, a range of hills on the north horizon, over which, once or twice at least in a lazy Sunday, a huge jet-plane, travelling so high it seemed slower than the flights of egrets or Hadeda ibis, would appear to be released and sail across the upper sky on its way to Europe. To people like those on the grass drinking wine and eating crisp lamb from their fingers, the sight brought a sensation of freedom: not the freedom associated with a great plane by those who long to travel, but the freedom of being down there on the earth, out in the fresh air of this place-to-get-away-to from the context of stuffy airports, duty-free drinks and cutlery cauled in cellophane.

Sometimes he went out alone on weekdays. It was an easy forty-minute drive at most, even through the five o’clock traffic. Once out of the city, there was another industrial area to get through, one of those Transvaal villages whose mealie fields had disappeared into factories with landscaped gardens, and whose main street was now built up with supermarkets, discount appliance stores and steak houses, but it was useful to be able to stop for cigarettes or delicatessen at the Greek’s on the way. After that it was a clear run beside the railway until you reached the African location, where they were inclined to come hurtling out of the gates — big, overloaded buses, taxis, lorryloads of people, bicycles and children all over the show. The location was endless; the high wire fence, sloping inwards and barbed at the top, cornered the turn-off from the tarred main road and followed the dirt one. The rows of houses were not yet built up to the boundary. In fact, on this side, they were still far across the veld, ridge after ridge of the prototype shelter that is the first thing little children draw: a box with a door in the middle, a window on either side, smoke coming out of a chimney. In the evenings and early mornings this smoke lay over them thick and softly; from one of those planes, one wouldn’t be able to make out the place at all. Then the road did a dog-leg away from the location. In the angle, old Labuschagne and his sons had their house; their cowsheds, fields and labourers’ shacks spread on both sides of the road. There was a windmill like a winged bird they never repaired. The next landmark he would tell his Sunday lunch-party visitors to look out for was the Indian store about two miles up, on the left. An enamel sign on the roof advertising a brand of soft drink long off the market, a wire stand with potatoes and withered cabbages on the verandah. From that point on, you could see the farm, see the mile of willows (people remarked that it would have been worth buying for the willows alone) in the declivity between two gently rising stretches of land, see the Katbosrand in the distance, see the house nobody lived in. No one would believe (they also said) the city was only twenty-five miles away, and that vast location just behind you. Peace. The upland serenity of high altitude, the openness of grassland without indigenous bush or trees; the greening, yellowing or silver-browning that prevailed, according to season. A landscape without theatricals except when it became an arena for summer storms, a landscape without any picture-postcard features (photographs generally were unsuccessful in conveying it) — a typical Transvaal landscape, that you either find dull and low-keyed or prefer to all others (they said).

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Conservationist»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Conservationist» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Conservationist» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.