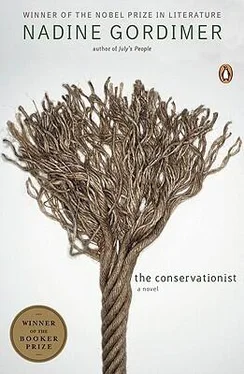

Nadine Gordimer - The Conservationist

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - The Conservationist» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1983, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Conservationist

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1983

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Conservationist: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Conservationist»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Conservationist — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Conservationist», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

They want to borrow the little pick-up, of course. It’s not necessary to wait for them to ask, not neighbourly. He is used to the conventions of open-handedness, sauna baths and trips to the Kruger Park. — But take my Toyota, why not? I’ll tell my boy. What day d’you want it? —

— Two days or so — Hansie ventures to put in.

— You see it’s out in Rustenberg, my late uncle’s place-Young Mrs De Beer cannot resist being expansive about something that must be recognized as within her province of interest. — He just passed away. Mmm, it was terrible, for a long time now he couldn’t — you know — couldn’t hold down his food. Not even water. —

The old man does not so much as acknowledge her as the source of prattle. He is looking sideways under his lids as if the interruption were something that has just walked through the room, his hand is raised and his lips are open, taking breath between sentences. - Monday will do. Monday will be all right. -

— My auntie wants to give up the place, yes, shame. —

— With pleasure. You just tell my boy, whenever it suits you. I don’t think we’ll be needing it for anything this week. -

— Oh that boy of yours — Two palms convivially flat on spread thighs, old De Beer alows another smile under the moustache. — He uses the tractor when he wants to go around to his friends, he doesn’t need the truck. —

He takes the joke against himself appreciatively; it is anyway at the same time a gesture of solidarity, from them, one employer telling another what he ought to know.

The old man refuses a third brandy. It looks as if they are going to go; but they don’t. The children have tripped out into the yard and returned with a captured kitten bunched up against the little one’s chest along with her skirt.

— You’re a man who travels all over. You must know about these things — there’s a family bible and other old stuff. Very old. Antique. Antique, hey? I think people pay a lot of money for old things these days. For investment, hey? You must come over to our place. I’ll let you have a look at it, when we bring it here. -

— Interesting, yes. —

— I collect myself. I have signed photographs of all our prime ministers. Since General Botha. My father fought with General Botha — you know that? And his father (a pause for attention) my grandfather — he fought in the Kaffir Wars. I have a coloured portrait of the late Dr Verwoerd, personally signed for me. I met him in Pretoria in July, nineteen-sixty. Yes. And I’ve got one signed by John Vorster, too. -

The terrified kitten escapes, skittering across the linoleum and under the sideboard. The mother is sucking the first joint of the child’s finger to take away the sting of a scratch. The child’s reddened face threatens them all with tears.

— Five chairs that belonged to my mother’s mother. They say they came from the Cape. Originally. But I’m interested in history — you understand. That’s my hobby. The history — of — the — Afrikaner. That’s what I like. Not furniture and so on. General Botha gave the photograph to my father himself, my father’s name is written on its — Henrik Barend De Beer, in General Botha’s handwriting —

The elder girl, motherly towards smaller ones as only black or Afrikaans children are, waggles the distraction of something she has picked up from the fireplace, and the threat dies down, but Hansie says in Afrikaans — No, she’ll break it, put it back. —

What is it anyway? There is nothing in the room, the house, that he values. What the elder girl is holding, uncertain whether to replace it or not, is one of those crude carvings of a black warrior with a spear and miniature hide shield that people buy in souvenir shops or airports all over Africa. He doesn’t know how it got into the house; the spear’s missing from the hole in the hand where these things are usually stuck.

— Let her take it. It’s nothing. -

— But don’t you want to keep it? — the mother says, knowing he’s a travelled man.

— I don’t know how it got here. You can buy them anywhere. -

— My grandfather — old De Beer is saying, risen from his chair without difficulty, considering his weight — My father’s father, had a kaffir doll they took from the chief’s place, there when they burned it in the war. Did you ever hear of Mod-jadji’s Kraal? Just near there. —

— A kaffir doll? —

— There in the Northern Transvaal. You know about the kaff rain queen? Well, up in those parts. One of their dolls they used for magic. It’s not much left of it; there were feathers and little bags of rubbish tied to it, but it’s old now. — The big shoulders move to indicate it is still somewhere around.

— You should hang on to that, Meneer de Beer. Museums in America pay fortunes these days to get hold of those things. -

— Say thank you nicely to the uncle. —

They take a detour, by way of the paddock where newly-calved cows are confined, to their car, trailing along behind Mehring and old De Beer. Hansie gives some advice about a calf. Jacobus has appeared in his gum-boots and torn overalls and is carrying feed; fortunately he always seems to remember you can’t drink and work at the same time. The vet has been to took at the calf; hardly off the plane from Tokyo when there was Jacobus on the phone, wanting the vet to be sent for.

— But is it taking the milk, now? —

— Yes, baas, she’s eat now. —

— But why does it still lie down all the time? Doesn’t it walk about? —

— Yes, baas, she’s walk. -

Jacobus, before the neighbouring farmer, agrees with everything that Mehring says, rather than gives an independent answer. He stands as if he has been called up in front of a class. Then, as though demonstrating what he has been taught, as though he didn’t do this every day when these men who are watching him are not there, he slops the mash with balletic accuracy into the troughs, spreads the hay in the byres.

— You’ve got this place going nicely. — Old De Beer graciously condescends by pretending to defer.

— This master will take the pick-up tomorrow or some other day this week. You’ll look out for him and give him the key, eh? —

With a sort of skip, knees bent, Jacobus has come to attention again. He agrees: Yes, baas.

While they are getting into the car a black man is trudging past carrying a plastic can; the endless Sunday traffic from compound to compound, every farm is a thoroughfare for them, nothing can be done about it: it is the same at De Beer’s place. But this one hails Mehring, he’s only a little drunk: Mina funa lo job? The tone is more threat than question. — No job! — Mehring throws up his hands.

Hansie is at least allowed to do the driving. - There’s a lot of loafers about. It’s that location. I can wish we were a hundred miles away from that location. Honestly. And you even had some skelm lying murdered in your place. It’s not safe. -

Old De Beer dismisses womanish speculation.

— My boys know I’ll shoot anyone I find coming near my cattle at night. They know that. They let their friends know that. —

The small child is prompted by the mother to wave from a window as the car drives away.

— What’s he going to do with the pick-up? — Jacobus follows at a short distance, back to the house, the way he does when he’s about to make a request. The farmer has turned round; they are facing each other, not really close enough for a conversation.

— He’s got some things to fetch from Rustenberg. - He turns back and is walking on while he speaks. They reach the screen door together and Jacobus comes in behind him: — Why he doesn’t take his brother’s lorry? —

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Conservationist»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Conservationist» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Conservationist» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.