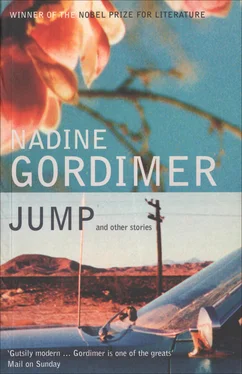

Nadine Gordimer - Jump and Other Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - Jump and Other Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Bloomsbury Paperbacks, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Jump and Other Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury Paperbacks

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Jump and Other Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Jump and Other Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is a vivid, disturbing and rewarding portrait of life in South Africa under apartheid.

Jump and Other Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Jump and Other Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The son came back surly and said nothing. His mother went up to challenge him face to face. And he answered in monosyllables she drew from him.

— It’s all right now. But you like to run, so run. — He felt she was teasing him, in the relief of tension. But she would not presume to laugh with a white man, her matronly dignity was remote as ever.

He shook hands with the old man, thanking him, thanking them all, awkwardly, effusively — no response, as he included the children, the son and daughter — hearing his own voice as if he were talking to himself.

He opened the door. With crossed arms, she contemplated him. — God bless you.—

The telling of it welled up in his mouth like saliva; he was on the right side, running home to tell what had happened to him. He swallowed and swallowed in urgency, unable to get there fast enough. Now and then his head tossed as he ran; in disbelief. All so quick. A good pace, quiet and even on the soft tarmac, not a soul in sight, and before you have the time to take breath — to prepare, to decide what to do — it happens. Suddenly, this was sensational. That’s how it will happen, always happens everywhere! Keep away. They came over, at him, not after him, no, but making him join them. At first he didn’t know it, but he was racing with them after blood, after the one who was to lie dying in the road. That’s what it really means to be caught up, not to know what you are doing, not to be able to stop, say no! — that awful unimagined state that has been with you all the time. And he had nothing to give the woman, the old man; when he ran, he kept on him only a few silver coins along with his house key in the minute pocket which, like the cushioned pump action of their soles, was a feature of his shoes. Could hardly tip her coins. But if he went back, another time, with say, a hundred rands, fifty rands, would he ever find the shack among so many? Should have asked her where she worked, obviously she must be a domestic or something like that, so that he could have rewarded her properly, found her at her place of employment. Where was it the husband held one of those chains you see before the ramp of a firm’s underground car park? Had she named the street? How shit-scared he must have been (he jeered) not to take in properly what the woman said! She probably saved his life; he felt the euphoria of survival. It lasted through the pacing of half a block. A car with men in golf caps, going to tee off early, passed him, and several joggers, just up, approached and went by with a comradely lift of the hand; he felt that his experience must blaze in his face if only they had known how to look, if only they had learnt.

But don’t exaggerate.

Had his life really been in danger? He could have been killed by a blow to get him out of the way, yes, that sledgehammer — it might have struck a glancing blow. The butcher’s knife, cleaver, whatever the horrible thing was with its sword-point and that woven bracelet like the pretty mats they make and sell on the streets, it could scalp you, open your throat with one swing. But they didn’t even seem to see him. They saw only the one they were after, and it wasn’t him. Under the rise and fall of his feet on the grassy suburban pavement blood drew its pattern on tarmac.

Who knew whether she was telling the truth when she said it was the police who sent them to make trouble?

He read the papers, for all he knew it could have been Inkatha murdering someone from the ANC, it could have been people from the street committees she said the boy belonged to, out to get a local councillor regarded as a government stooge, it could have been ANC people avenging themselves on a police informer. He didn’t know how to read the signs of their particular cause as someone like her would from the rags they had tied round their heads or the kind of weapons they’d improvised for themselves, the cries they chanted. He had to believe her, whatever she’d chosen to tell him. Whatever side she was on — god knows, did she know herself, shut in that hovel, trying to stay alive — she had opened her door and taken him in.

Why?

Why should she have?

God bless you.

Out of Christian caritas? Love — that variety? But he was not welcome in the hovel, she had kept the distaste, the resentment, the unease at his invasion at bay, but herself had little time for his foolish blundering. What do you want to come near this place for. He heard something else: Is there nowhere you think you can’t go, does even this rubbish dump belong to you if you need to come hiding here, saving your skin. And he had shamefully wanted to fling himself upon her, safe, safe, reassured, hidden from the sound and sight of blows and blood as he could be only by one who belonged to the people who produced the murderers and was not a murderer.

As he came level with the security cage of the electricity sub-station, the take-away, and then the garage and the houses prefiguring his own, the need to tell began to subside inside him with the slowing of his heartbeat. He heard himself describing his amazement, his shock, even (disarmingly honest confession) his shit-scaredness, enjoying the tears (dread of loss) in the eyes of his wife, recounting the humble goodness of the unknown woman who had put out her round butterscotch-coloured arm and pulled him from danger, heard himself describing the crowded deprivation of the shack where too few possessions were too many for it to hold, the bed curtained for some attempt at the altar of privacy; the piously sentimental conclusion of the blessing, as he was restored to come home for breakfast. The urge to tell buried itself where no one could get it out of him because he would never understand how to tell; how to get it all straight.

— A bit excessive, isn’t it? Exhausting yourself — His wife was half-reproachful, half-amused at the sight of shining runnels on his face and his mouth parted the better to breathe. But she was trailing her dressing-gown, barefoot, only just out of bed and she certainly had no idea how early he had left or how long he had been absent while the house slept. Over her cereal his daughter was murmuring to a paper doll in one of the imaginary exchanges of childhood, he could hear the boys racing about in the garden; each day without fingerprints, for them.

He drank a glass of juice, and another, of water. — I’ll eat later.—

— I should think so! Go and lie down for a while. Are you trying to give yourself a heart attack? What kind of marathon is this. How far have you been today, anyway?—

— I don’t keep track.—

— Yes, that’s evident, my darling! You don’t.—

In the bedroom the exercise bicycle, going nowhere.

In brokerage, her darling, resident at this address. He took off his running shoes and threw his shirt on the carpet. He stank of the same sweat as those he was caught up among within a pursuit he did not understand.

The unmade bed was blissful. Her lilac-patterned blue silk curtains were still drawn shut but the windows were open and the cloth undulated with a breeze that touched his moist breast-hair with a light hand. He closed his eyes. Some extremely faint, high-pitched, minute sound made timid entry at the edge of darkness; he rubbed his ear, but it did not cease. Longing to sleep, he tried to let the sound sink away into the tide of his blood, his breath. If he opened his eyes and was distracted by the impressions of the room — the dressing-table with the painted porcelain hand where her necklaces and ear-rings hung, the open wardrobe with his ties dangling thick on a rack, a red rose tripled in the angle of mirrors, his briefcase abandoned for the weekend on the chaise-longue, the exercise bicycle — he heard the sound only by straining to. But the moment he was in darkness it was there again: plaintive, feeble, finger-nail scratch of sound. He staggered up and went slowly about the room in search of the source like a blind man relying on one sense alone. It was behind a wall somewhere, penetrating the closed space of his head from some other closed space. A bird. A trapped bird. He narrowed the source; the cheeping came from a drain-pipe outside the window.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Jump and Other Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Jump and Other Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Jump and Other Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.