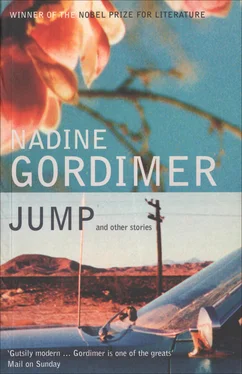

Nadine Gordimer - Jump and Other Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - Jump and Other Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Bloomsbury Paperbacks, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Jump and Other Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury Paperbacks

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Jump and Other Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Jump and Other Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is a vivid, disturbing and rewarding portrait of life in South Africa under apartheid.

Jump and Other Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Jump and Other Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Everyone bursts the silence like schoolchildren let out of class.

‘Where?’

‘How does he know?’

‘What’s he say?’

He keeps them waiting a moment, his hand is raised, palm up, pink from immersion in the washing-up. He is wiping it on his apron. ‘My wives hear it, there in my house. Zebra, and now they eating. That side, there, behind.’

The black man’s name is too unfamiliar to pronounce. But he is no longer nameless, he is the organizer of an expedition; they pick up a shortened version of the name from their host. Siza has brought the old truck, four-wheel drive, adapted as a large station wagon, from out of its shed next to his house. Everybody is game, this is part of the entertainment the host hoped but certainly could not promise to be lucky enough to provide; all troop by torchlight the hundred yards from the lodge, under the Mopane trees, past the bed of cannas outlined with whitewashed stones (the host never has had the heart to tell Siza this kind of white man’s house does not need a white man’s kind of garden) to Siza’s wives’ pumpkin and tomato patch. Siza is repairing a door-handle of the vehicle with a piece of wire, commanding, in his own language, this and that from his family standing by. A little boy gets underfoot and he lifts and dumps him out of the way. Two women wear traditional turbans but the one has a T-shirt with an advertising logo; girl children hang on their arms, jabbering. Boys are quietly jumping with excitement.

Siza’s status in this situation is clear when the two wives and children do not see the white party off but climb into the vehicle among them, the dry-soled hard little feet of the children nimbly finding space among the guests’ shoes, their knobbly heads with knitted capping of hair unfamiliar to the touch, flesh to flesh, into which all in the vehicle are crowded. Beside the girl with her oiled face and hard slender body perfumed to smell like a lily there is the soft bulk of one of the wives, smelling of woodsmoke. ‘Everybody in? Everybody okay?’ No, no, wait — someone has gone back for a forgotten flash-bulb. Siza has started up the engine; the whole vehicle jerks and shakes.

Wit is not called for, nor flirtation. He does what is expected: runs to the lodge to fetch a sweater, in case his wife gets chilly. There is barely room for him to squeeze by; she attempts to take a black child on her lap, but the child is too shy. He lowers himself somehow into what space there is. The vehicle moves, all bodies, familiar and unfamiliar, are pressed together, swaying, congealed, breathing in contact. She smiles at him, dipping her head sideways, commenting lightly on the human press, as if he were someone else: ‘In for the kill.’

It is not possible to get out.

Everyone will be quite safe if they stay in the car and please roll up the windows, says the host. The headlights of the old vehicle have shown Siza trees like other trees, bushes like other bushes that are, to him, signposts. The blundering of the vehicle through bush and over tree-stumps, anthills, and dongas has been along his highway; he has stopped suddenly, and there they are, shadow-shapes and sudden phosphorescent slits in the dim arch of trees that the limit of the headlights’ reach only just creates, as a candle, held up, feebly makes a cave of its own aura. Siza drives with slow-motion rocking and heaving of the human load, steadily nearer. Four shapes come forward along the beams; and stop. He stops. Motes of dust, scraps of leaf and bark knocked off the vegetation float blurring the beams surrounding four lionesses who stand, not ten yards away. Their eyes are wide, now, gem-yellow, expanded by the glare they face, and never blink. Their jaws hang open and their heads shake with panting, their bodies are bellows expanding and contracting between stiff-hipped haunches and heavy narrow shoulders that support the heads. Their tongues lie exposed, the edges rucked up on either side, like red cloth, by long white incisors.

They are dirtied with blood and to human eyes de-sexed, their kind of femaleness without femininity, their kind of threat and strength out of place, associated with the male. They have no beauty except in the almighty purpose of their stance. There is nothing else in their gaunt faces: nothing but the fact, behind them, of half-grown and younger cubs in the rib-cage of a zebra, pulling and sucking at bloody scraps.

The legs and head are intact in dandyish dress of black and white. The beast has been, is being eaten out. Its innards are missing; the half-digested grasses that were in its stomach have been emptied on the ground, they can be seen — someone points this out in a whisper. But even the undertone is a transgression. The lionesses don’t give forth the roar that would make their menace recognizable, something to deal with. Utterances are not the medium for this confrontation. Watching. That is all. The breathing mass, the beating hearts in the vehicle — watching the cubs jostling for places within the cadaver; the breathing mass, the beating hearts in the vehicle — being watched by the lionesses. The beasts have no time, it will be measured by their fill. For the others, time suddenly begins again when the young doctor’s girl-friend begins to cry soundlessly and the black children look away from the scene and see the tears shining on her cheeks, and stare at her fear. The young doctor asks to be taken back to the lodge; the compact is broken, people protest, why, oh no, they want to stay and see what happens, one of the lionesses has broken ranks and turns on a greedy cub, cuffing it out of the gouged prey. Quite safe; the car is perfectly safe, don’t open a window to photograph. But the doctor is insistent: ‘This old truck’s chassis is cracked right through, we’re overloaded, we could be stuck here all night.’

‘Unreal.’ Back in the room, the wife comes out with one of the catch-alls that have been emptied of dictionary meaning so that they may fit any experience the speaker won’t take the trouble to define. When he doesn’t respond she stands a moment, in the doorway, her bedclothes in her arms, smiling, gives her head a little shake to show how overwhelming her impression has been.

Oh well. What can she expect. Why come, anyway? Should have stayed at home. So he doesn’t want to sleep in the open, on the deck. Under the stars. All right. No stars, then.

He lies alone and the mosquitoes are waiting for his blood, upside-down on the white board ceiling.

No. Real. Real. Alone, he can keep it intact, exactly that: the stasis, the existence without time and without time there is no connection, the state in which he really need have, has no part, could have no part, there in the eyes of the lionesses. Between the beasts and the human load, the void. It is more desired and awful than could ever be conceived; he does not know whether he is sleeping, or dead.

There is still Sunday. The entertainment is not over. Someone has heard lions round the lodge in the middle of the night. The scepticism with which this claim is greeted is quickly disproved when distinct pugs are found in the dust that surrounds the small swimming-pool which, like amniotic fluid, steeps the guests at their own body temperature. The host is not surprised; it has happened before: the lionesses must have come down to quench the thirst their feasting had given them. And the scent of humans, sleeping so near, up on the deck, the sweat of humans in the humid night, their sighs and sleep-noises? Their pleasure- and anxiety-emanating dreams?

‘As far as the lions are concerned, we didn’t exist.’ From the pretty girl, the remark is a half-question that trails off.

‘When your stomach is full you don’t smell blood.’

The ex-prisoner is perhaps extrapolating into the class war? — the wit puts in, and the ex-prisoner himself is the one who is most appreciatively amused.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Jump and Other Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Jump and Other Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Jump and Other Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.