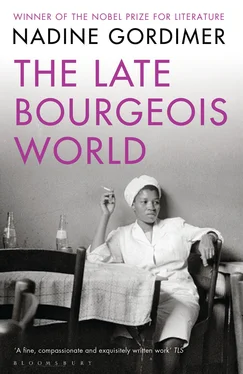

Nadine Gordimer - The Late Bourgeois World

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - The Late Bourgeois World» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Bloomsbury Paperbacks, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Late Bourgeois World

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury Paperbacks

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Late Bourgeois World: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Late Bourgeois World»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Now Liz has been asked to perform a direct service for the black nationalist movement, at considerable danger to herself. Can she take such a risk in the face of Max's example of the uselessness of such actions? Yet… how can she not?

The Late Bourgeois World — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Late Bourgeois World», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

While we were talking I was aware, as if standing aside from us both, that this other dialogue of ours was soothingly being taken up. Our speaking voices went on, a bit awkwardly, but, like the changing light in the Son et Lumière performances we saw in France, illuminating, independent of the narration, the real scene of events as it moved from walls to portal to courtyard and window, the light and shadow of the real happening between us was going on as usual, in silence.

Then instead of saying, ‘You have a point there,’ Graham said, ‘How would you say things are with us?’

For a second I took it as going straight to all that we competently avoided, a question about him and me, the lie he had caught me out with on my hands — and I could feel this given away, in my face.

I did not know what to say.

But it was a quiet, impersonal demand, the tone of the judge exercising the prerogative of judicial ignorance, not the partisan one of the advocate cross-examining. There was what I can only describe as a power failure between us; the voices went on but the real performance had stopped in darkness.

I said, ‘Well, I’d find it difficult to define — I mean, how would you describe — what could one say this is the age of ? Not in terms of technical achievement, that’s too easy, and it’s not enough about us — about people — is it?’

‘Today, for instance.’ He was serious, tentative, sympathetic.

Yes, this day. This morning I was driving through the veld and it was exactly the veld, the sun, the winter morning of nine years old, for me; for Max. The morning in which our lives were a distant hum in the future, like the planes a distant hum in the sky (there was a big air-force training camp, near my home, during the war). Grow big, have a job, be married, pray to the blond Christ in the white people’s church, give the nanny your old clothes. This same morning and our lives were here and Max had been in prison and was dead and I was not a widow. What happened? That’s what she asked, the old lady, my grandmother. And while I was driving through the veld to see Bobo (Max heard the ducks quacking a conversation he never understood) a man was walking about in space. I said, ‘Graham, what on earth do you think they’ll call it in history?’ and he said, ‘I’ve just read a book that refers to ours as the Late Bourgeois World. How does that appeal to you?’

I laughed. It went over my skin like wind over water; that feeling you get from a certain combination of words, sometimes. ‘It’s got a nice dying fall. But that’s a political definition, they’re no good.’

‘Yes, but the writer — he’s an East German — uses it as a wider one — it covers the arts, religious beliefs, technology, scientific discoveries, love-making, everything —’

‘But excluding the Communist world, then.’

‘Well no, not really’ — he loves to give me a concise explanation — ‘it exists in relation to the early Communist world — shall we call it. Defining one, you assume the existence of the other. So both are part of a total historical phenomenon.’

I poured him another drink because I wanted him to go, and although he wanted to go, he accepted it. ‘Did you work all afternoon? Or did you really sleep?’

But I knew that he had worked; he gave the admission of a dry, dazed half-smile, something that came from the room where he’d been shut up among documents, as a monk, who during his novitiate still makes some sorties into the life outside, is claimed by the silence of the cell that has never really relinquished him. Even the Friday night love-making had not made Graham sleepy in the afternoon; in that room of his, he wrote and intoned into the dictaphone, alone with his own voice. I’ve heard it sometimes from outside the door; like someone sending up prayer.

I mentioned I’d noticed that the arrow-and-spear sign was still on the walls of the viaduct near the Home.

‘I’m not surprised. I think there are a few new ones round the town, too. Somebody’s brave. Or foolhardy.’ He told me last week that a young white girl got eighteen months for painting the same symbol; but of course in the Cape black men and women are getting three years for offences like giving ten bobs’ worth of petrol for a car driven by an African National Congress member.

‘D’you think it’s all right, using that spear thing? I mean, when you think who it was who had the original idea.’ It came out in a political trial not long ago that this particular symbol of resistance was the invention of a police agent provocateur and spy. I’d have thought they’d want to find another symbol.

He laughed. ‘I don’t suppose the motives of the inventor’ve much to do with it. After all, look at advertising agencies — do you think the people who coin the selling catchword believe in what they’re doing?’

‘Yes, I suppose so. But it’s queer. A queer situation. I mean one could never think it would be like that.’

We were silent for a moment; he was, so to speak, considerately bare-headed in these pauses in which the thought of Max was present. There was nothing to say about Max, but now and then, like the silent thin spread of spent water coming up to touch your feet on a dark beach at night, his death or his life came in, and a commonplace remark turned up reference to him. Graham asked, ‘The flowers arrive for your grandmother all right?’ I told him how they were kept outside the door; and how she had cried out when she saw a figure in the doorway.

‘It’s natural to be afraid of death.’ Just as if he were advising a dose of Syrup of Figs for Bobo (one of the fatherly gestures he sometimes boldly makes).

‘Maybe. But she’s never had to put up with what’s natural. Neither grey hairs nor cold weather. It’s true — until two or three years ago, when she became senile, she hadn’t lived through a winter in fifteen years — she flew from winter in England to the summer here, and from winter here to summer in England. But for this, now, nothing helps.’

‘Like the common cold,’ he said, standing up suddenly and looking down at me; almost amusedly, almost bored, accusingly. So he dismisses a conversation, or makes a decision. ‘Can you take me now?’ But he doesn’t understand. Since you have to die you ought to be provided with a perfectly ordinary sense of having had your fill. A mechanism like that which controls other appetites. You ought to know when you’ve had enough — like the feeling at the end of a meal. As simple and ordinary as that.

I drove him home. His name is on the beautifully polished bronze plate on the gateway and a wrought-iron lantern is turned on by the servants at dusk every day above the teak front door. When he got out of the car I asked him to supper tomorrow. There was no difficulty about the lie; it didn’t seem to matter at all, everything was slack and somehow absent-minded between us. As soon as I’d dropped him, I drove home like a bat out of hell, feeling pleasurably skilful round corners, as I find I do when I’ve had just one sharp drink on an empty stomach. I had to get on and finish with the onions and have a bath, before half-past seven.

I’d said about half-past seven, but I could safely count on eight o’clock, so there was plenty of time.

I was expecting Luke Fokase. He phoned the laboratory on Thursday. ‘Look, how are things, man? I’m around. If I should drop in on Saturday, is that all right with you? I’m just around for a short time but I think I’ll still make it.’

We don’t use names over the telephone. I said, ‘Come and eat with me in the evening.’

‘Good, good. I’ll drop by.’

‘About half-past seven.’

I don’t know why I asked him again. I rather wish he’d leave me off his visiting list, leave me alone. But I miss their black faces. I forget about the shambles of the backyard house, the disappointments and the misunderstandings, and there are only the good times, when William Xaba and the others sat around all day Sunday under the apricot tree, and Spears came and talked to me while I cooked for us all. It comes back to me like a taste I haven’t come across since, and everything in my present life is momentarily automatous, as if I’ve woken up in a strange place. And yet I know that it was all no good, like every other luxury, friendship for its own sake is something only whites can afford. I ought to stick to my microscope and my lawyer and consider myself lucky I hadn’t the guts to risk ending up the way Max did.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Late Bourgeois World»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Late Bourgeois World» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Late Bourgeois World» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.