Nadine Gordimer - A Sport of Nature

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - A Sport of Nature» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Bloomsbury UK, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

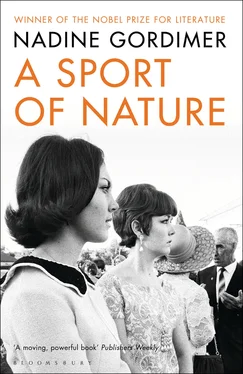

- Название:A Sport of Nature

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury UK

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Sport of Nature: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Sport of Nature»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Sport of Nature — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Sport of Nature», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Arnold would walk up the beach with newcomers; they sat apart, and the flash of his rimless glasses was enough to keep away anyone who might think of joining them. Their absorption was intense as can be only in those in whom singleness of purpose has taken hold of every faculty of intellect and feeling, so that even if that purpose is to be frustrated for a lifetime in prison, or to be exercised far removed from the people and places where its realization begins to take place, all other purposes in life are set aside, perhaps for ever, because each in some way contradicts the single one. Arnold was a lawyer — like Joe — who would never practise law again; the law in his country enforced the very social order his purpose was to end. He had a wife — like Pauline? — with whom he would never set up home again in the house where only white people could live. His children would grow up here and there — like Hillela herself — without his knowing them; there could be no family life for whites, with blacks, at best, illegally given a place in their converted garages. Christa’s brother with his farm on land from which blacks had been removed could not be her brother while Sophie and Njabulo were her family. Mothering girls without a decent pair of jeans to their names, she could not have married the Afrikaner doctor in Brits who was in love with her, and mothered children he would take to the segregated Dutch Reformed Church every Sunday.

Arnold, rising from a conclave, paused on the beach as a bee holds, in mid-air. At the signal of the flower-yellow swimsuit, he waded into the water. There was no surf. A transparent grass-green was a huge lens placed from shore to reef over sand like ground crystal. He kept his own glasses on when he swam; the image of the girl’s body under water swayed and shone, broke and reformed. His hairy toes struck him as ugly as crabs. He and she began to swim around each other. He had a soft way of speaking, conspiratorial rather than sexually modulated. — So you’ve got yourself nicely fixed up.—

— Oh …? Yes. Somewhere to stay.—

— Clever girl. Lucky Udi.—

— I was fine with Sophie and Njabulo but it was hard on them.—

— Left the beach — high and dry.—

She pinched her nose between thumb and forefinger and submerged herself, like a child at a swimming pool. When she came up, smiling, he was still talking.‘

— You’d better watch out, with him.—

— He’s a good friend of Christa’s, really nice. I’ve got a room as big as Sophie’s whole flat! You can see the town and the bay.—

— Are you sure it’s to yourself?—

She turned like a porpoise, floated on her back, water beaded her flesh with light in the sun, in his sight.

— Well of course. I want Christa to come and share, but she won’t leave the Manakas.—

— He won’t need an invitation in his own house.—

She turned her head; not understanding, or thinking she ought to pretend not to? He took off his glasses, which she had splashed. The little beach girl was a lovely blur. He put them back again. — You’d better keep the door locked. Or maybe it hasn’t got one?—

— Arnold … he’s an old man … old as my uncle … — It was in character with the footlooseness of this pretty girl, the ruptured kinships and displaced, marginal emotions of exile that, to his ears, made a slip of the tongue where the usual comparison would have been with a father.

— You don’t know old men. The older we get, the younger we like ’em.—

— Well how would you know, you’re not old.—

— Thank you for those kind words, obvious as they are. Isn’t there anything you know without experiencing it for yourself?—

Both floated on their backs now, and it was not only the water-jewelled breasts, down to where the yellow swimsuit just covered stiff nipples, that surfaced, but also the thick index finger and fist of his penis and testicles under their pouch of wet blue nylon. They saw what there was to be seen of each other, while feeling identical delicious coolness and heat — the water on submerged and the sun on exposed flesh.

— Didn’t you hear what I asked?—

— I thought you were telling me something. — A figure of such authority on Tamarisk; she had seen how the appearance of a line above the bridge of his nose made a voice stop short in mid-sentence, and how, when he was asked the kind of question that was not to be asked in such circles, his evasion of an answer came from complete intelligence of all that happened, was thought, discussed, investigated and decided there. What could he be interested in that she could tell him? The odd hours they had spent together (he worked very hard, even on Tamarisk he had time to take pleasure only when he left the last sandy foothold of the continent and entered the neutrality of the non-human element, the water) those times — caresses, the universal intelligence of pleasurable sensations, a rill from it present in wet coolness and heat, now — were the exchange with him in which she could take part. — I don’t know. Let me think. — Her eyes were closed against the sun; her smiling lips moved, he saw her so seriously young that she spelled out thoughts to herself the way children learning to read silently mouth words. The giant of desire woke in him to kiss her while she saw nothing but the red awning of her eyelids, and he slew him with the sling of priorities. Sexual pleasure was everyone’s right; dalliance when he had simply taken a breather from the discussion on shore was not something he himself or those who could watch from Tamarisk should tolerate.

— No. Not really. No. — She kept her eyes closed, screwed up; the sun was making her see fire. — How can anyone know what hasn’t happened to them? People like you, who’ve been in prison … and once or twice others, I’d heard talking, back there. You can describe what it was like, but I … I never, I don’t really believe it’s all it’s like. The same with leaving the country. I was always hearing about it. I even once saw someone on his last night. But it’s only now that I’ve done it … it’s different from what you’re told, what you imagine. You are all different, all of you … from the speeches. Where I lived — at home, when I was still in what was my home — everything was read out from newspapers, everything was discussed, I went to a court once and there was another kind of talk, another way of words dealing with things that had happened … somewhere else, to somebody else … I couldn’t know. I can know what happens to me.—

— You’ll burn your eyelids. Turn over. — But what you read, what you learn, what people tell you, what you observe — good god, that’s what happens to you, as well! Not everything can be understood only through yourself — what do you mean? — and anyway, isn’t your comprehension, your mind, yourself? What are you saying? You don’t trust anything but your own body? It’s a nice one, my god, certainly — but I don’t believe you know what you’re saying.—

— Thinking about what happens to myself — yes, of course, that I can know .—

— Someone needs to take you in hand, my girl. You are not a fully conscious being. I wish I had the time. And it would be quite pleasant … I can imagine the sort of home you come from. Girls the ornaments who spoil their decorative qualities and betray their class as soon as they begin to think. How in god’s name did you get here? I mean I know — but how’d you ever take up with that fellow? You know he was a liar and a double-dealer? He was for us and at the same time he was really working for PAC*? And maybe if we’d not run him out of here he would be working for the government back there, as well.—

— He was collecting material for a book. That’s why he went all over the show, he had to talk to all kinds of people.—

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Sport of Nature»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Sport of Nature» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Sport of Nature» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.