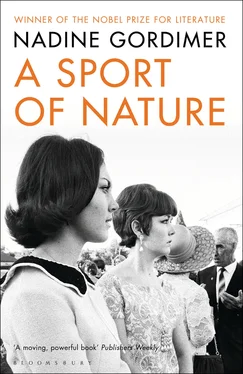

Nadine Gordimer - A Sport of Nature

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - A Sport of Nature» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Bloomsbury UK, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Sport of Nature

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury UK

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Sport of Nature: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Sport of Nature»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Sport of Nature — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Sport of Nature», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Pauline burst the news to Joe: —That’s a laugh! Hillela, ‘having to flee the country’! That’s how my sister puts it, I could feel her trembling in her boots, at the other end of the phone … What could Hillela have done, she didn’t even have any interest in helping black schoolchildren on Saturday mornings! Smoking pot in a coffee bar, that was more in that little girl’s line. — Joe’s customary considered reactions meant that Pauline did not notice he already knew what she had just learned. But he told her, then, of the girl’s visit to his rooms because he saw that jealousy was mixed, in distress, with guilt, for Pauline. He made the mistake of phrasing it: —She came to me.—

— Came to you! —

How expressive these faces of his women were, how frightening in their importunity: the dyes of hurt, resentment, indignation were always so quickly there to flood the cheeks and brow of Pauline.

— It was what she was told to do, you know.—

— But this kind of trouble! Hillela! She has no political sense, no convictions, not the faintest idea, that child! Hillela a political refugee — from what, I’d like to know! Now no-one can keep an eye on her. None of us can do anything, she’s made sure of that. We’ve let it happen. Hillela a political refugee. What idiocy. What a final mess. God knows what will become of her.—

— She has the money. In good foreign currency.—

— And how did you get that for her?—

But what was arranged within the walls of professional confidence was not to be divulged further; his wife knew that he must have done what the ethics of that profession did not allow, and that he had never done before — contravened currency restrictions in some shady way. Hillela, of course, would not stop to think of consequences for others, then as at any other time. Yet suddenly anger became tears in Pauline’s eyes.

— How long will it last.—

At least Joe’s breach of confidence enabled her to telephone Olga and let her know that no-one in Pauline’s family was trembling in their boots; on the contrary, Joe had done the practical thing, Joe had seen to it that the girl had funds of some sort for whatever predicament, real or imaginary, she had got herself into.

In July a country estate, in the area near the city where the rich lived to escape suburbia, was raided by the police. The people living at the evocatively-named Lilliesleaf Farm were not enjoying their gardens and stables but were the High Command of liberation movements planning to put an end to the subjection of blacks by whites by whatever means whites might finally make necessary. Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki, Ahmed Kathrada and a whole bold houseparty of others, white and black, were arrested, and Nelson Mandela was brought from prison to be tried with them on new charges. Olga — by now afraid to talk over the telephone; the girl was a blood relation, after all, it couldn’t be denied if the police should make enquiries — came to see her sister. Was there anything to the story that it was known at the agency Hillela had gone with a man? Only a month earlier? Maybe he was mixed up in the Farm affair, perhaps it had been just in time …? Pauline gave a light laugh at this— flattery; at Olga. But the idea provided the base for some sort of explanation that slowly came to serve, in the end. Attached herself to some man — that’s what it was all about. He was the one who had to go.

Pauline and Olga were only two of three sisters, after all; still.

Attached herself to some man.

My poor Ruthie.

I, me .

Time, now. They had always, they went on fitting that self into their conjugations, leaving out the first person singular. Except one of the cousins, poor boy; he didn’t .

It’s not possible to move about in the house of their lives. A china cat survived two centuries and was broken. Awful .

Intelligence

Tamarisk Beach in the late afternoons was the place of resurrection. Those who had disappeared from their countries while on bail, while on the run, while under house arrest; that non-criminal caste of people from all classes and of all colours strangely forced to the subterfuge of real criminals evading justice — they reappeared on foreign sand in swimming shorts and two-piece swimsuits. While they swam, their towels, shoes, cigarettes were dumped for safety in numbers under the three etiolated tamarisks for which the British colonial families had named the beach once reserved for their use. Now hungry, raucous local youths hung about there all day, acrobatically light-fingered. If those of the new caste — big men, some of them, cultivated on distant soccer fields — looked warningly at the boys, they jacked themselves swiftly up palm boles and laughed, jeering from the top in their own language, that not even the strangers who were black as they were understood. Sometimes a coconut came down from there like a dud bomb, unexploded, from the countries left behind; the local boys fought over it just the way the scorpions they would set against one another in a sand arena fought, and the victor hawked it round for sale.

There was no respite from heat in weeks passing, months passing. Like exile itself, a sameness of time without the trim and shape of home and work, the heat was unattached to any restraints of changing seasons. Only in the late afternoons did something stir sameness: a breath blew in under it, every afternoon, one of those trade winds that had set history on course towards prehistory, bringing first the Chinese and then the Arabs to that coast. It brought to Tamarisk Beach the men from alley offices with unpaid telephone bills and liberation posters, from the anterooms of European legations where they waited to ask for arms and money, and from the comings and goings between taken-over colonial residences and ex-governors’ offices where rival political groups struggled to keep their credentials acceptable to their host country, lobbying, placing themselves in view of the powerful, watching who in the first independent black government there was on his way up to further favour, and worth cultivating, and who was dangerous to be associated with because he might be on his way down.

The exile caste came to the beach for air. And then the original impulse — to breathe! — became part of a social ritual, a formation of a new regularity, a necessary ordering of a place where other needs that cannot be done without might be met. Many had experienced this kind of formation even in jail. On Tamarisk Beach they strolled through the colonnades of palms, avoiding or meeting each other, eyeing across a stretch of sand faces separated by the distance of alliances dividing Moscow and Peking, East Germany and the United States, or the desert distance of solitary confinement and the stony alienation that succeeds screams in those who have known torture since last meeting. They paused to pick tar and oil-slick from the soles of their feet, and scratched the hair on their chests, smoked, shook water from their ears — just for those hours in the late afternoon could have been holiday-makers anywhere. There were some women among them, political lags, like the men, and defiantly feminine, keeping up with curled, home-tinted hair, ingenious cut of local cotton robes as sun-dresses, and cheap silver-wire jewellery from the market craftsmen, the high self-image needed to defeat the humiliations of prison. There was sensuality on Tamarisk Beach. It came back with the relief of a breeze; it came back with the freeing of bodies from the few clothes thrust into a suitcase for exile and worn in the waitingrooms and makeshift living quarters of exile. It became a pattern of human scale made by strollers in the monumental arcade of palms and swimmers dabbling in the great Indian Ocean at the edge of a continent.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Sport of Nature»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Sport of Nature» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Sport of Nature» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.