A bricklayer since childhood. When he turned eighteen, he had to stop working to do his military service.

They assigned him to the artillery brigade. One day during target practice, he was ordered to shoot at an empty house.

A house like any other, sitting by itself in the countryside. He had learned how to aim, but he could not bring himself to do it. They screamed out the order a second time, but he just couldn’t.

He had built quite a few houses like that one. He could have explained that a house has legs rooted in the ground, and a face like in a child’s drawing, eyes for windows, a mouth for a door, and deep inside a soul left by those who built it and memories of everyone who lived in it.

He could have explained all that, but he didn’t say a thing. If he had, they would have shot him for idiocy. He stood at attention and remained silent. He ended up in the clink.

Carlo Barbaresi tells this story to a group of friends around a campfire in the mountains of Argentina. It’s about his father in Italy, back in the time of Mussolini.

It wasn’t just any Sunday afternoon in 1967.

It was the afternoon of the classic. Club Santafé against Millonarios, and the entire city of Bogota was in the stands. Outside the stadium there was nobody except the crippled and the blind.

The match seemed to be headed for a tie. Then Omar Lorenzo Devanni, the Santafé striker, fell. The referee whistled a penalty kick.

Devanni was bewildered. No one had touched him; he simply tripped. He wanted to tell the referee it was a mistake, but the Santafé players picked him up and carried him on a stretcher to the white penalty spot. There was no way out of it. The stadium was roaring, on the edge of delirium.

Between the posts, the hangman’s posts, waited the keeper.

Devanni placed the ball on the white spot.

He knew what he was going to do and the price he was going to pay. He chose ruin; he chose glory: Devanni took a running start and with all his might kicked it wide, far wide of the goal.

Four and a half centuries ago in Geneva, they used green wood to burn Miguel Servet alive. He had gone there to escape the Inquisition, but Calvin sent him to the stake.

Servet believed no one should be baptized before becoming an adult, he had doubts about the mystery of the Holy Trinity, and he stubbornly insisted on teaching that blood flows through the heart and is purified in the lungs.

His heresies condemned him to the life of a gypsy. Before they caught up to him, he’d changed countries, homes, trades, and names many times.

Servet was burned on a slow fire along with the books he had written. On the cover of one of them was an engraving of Sampson carrying a tremendously heavy door on his back. Underneath, it said, “I carry my freedom with me.”

Six centuries after its founding, Rome decided that the year would begin on the first day of January.

Before then, years began on March 15.

The date had to be changed for reasons of war.

Spain was on fire. The rebellion, which challenged the empire’s might and devoured thousands upon thousands of legionaries, obliged Rome to change the tally of its days and the cycles of its affairs of state.

The uprising lasted many long years until at last the city of Numantia, capital of the Hispanic rebels, was besieged, vanquished, and burned to the ground.

Its remains lie on a hill, surrounded by fields of wheat at the edge of the Duero River. Of the city that changed the world’s calendar forever, practically nothing is left.

But when we raise our glasses at midnight every December 31, we drink a toast to her, whether or not we realize it: may there always be another year and people who are free.

We are daughters and sons of the days. “What is a person in the road?”

“Time.”

The Maya, ancient masters of such mysteries, have not forgotten that we come from time and are made of time, which is born with every death.

And they know that time reigns supreme and it laughs whenever money tries to buy it,

surgery tries to erase it,

pills try to silence it,

and machines try to measure it.

But when the rebellious Indians of Chiapas sat down to talk peace, a Mexican government official had their number. Pointing to his own wrist and to those of the Indians, he decreed: “We use Japanese watches, and you use Japanese watches. For us it is nine in the morning, and for you it is nine in the morning. So stop pestering me with all this nonsense about time.”

When the season is the enemy, bearing black skies and days of ice and storms, the newborn alfalfa sits quietly and waits. The timid sprouts go to sleep, and in their slumber they survive while the hard times last, no matter how long that may be.

When sunny days finally come and the skies turn blue and the ground begins to warm, the alfalfa awakens. Then, only then, does it grow. It grows so fast you can see it, pushed up from the roots by gusts not made of air.

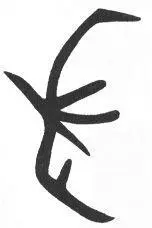

In the mountains of Cajamarca, amid the peaks that took the longest to awaken and arise when the world was born, there are many figures painted by artists without names.

Those colorful tattoos on rock faces have survived for thousands of years, despite the ravages of weather.

The paintings are or aren’t, according to the time of day. Some catch fire when the day begins and go out by noon. Others change shape and color throughout the long march of the sun from dawn to dark. Still others appear only with dusk.

The paintings were created by human hand, but they are also works of light, the light that time sends day after day, and they are at her beck and call. She, the light, that other artist, queen and lady, conceals them and unveils them as and when she wishes.

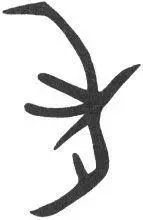

The largest birds in the world fly not in the sky but in the ground.

They were sketched by the ancient inhabitants of Nazca, who knew how to summon marvels from the bare desert.

Seen from the ground, the lines say nothing. They are but long canals of stone and dust, which vanish in the distance on that high plain of dust and stone.

Seen from the air, those wrinkles in the desert form gigantic birds with outstretched wings.

The drawings are two or two and a half thousand years old. Airplanes, as far as we know, did not exist. For whom were they made? For whose eyes? Experts disagree.

I think, I wonder, could those perfect lines, which glisten in the dry air, have been born so the heavens could see them?

The heavens offer us their splendid designs, etched with stars or clouds, and it’s only right that we show our appreciation. The earth is not incapable. Perhaps that is what those people who turned the desert into a masterpiece wished to say: that the earth, too, can draw the way the heavens draw, and can fly without ever leaving the ground, on the wings of the birds it creates.

Читать дальше