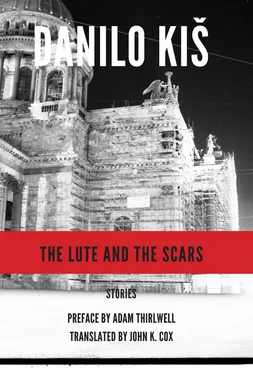

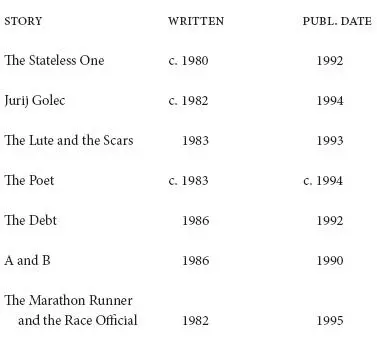

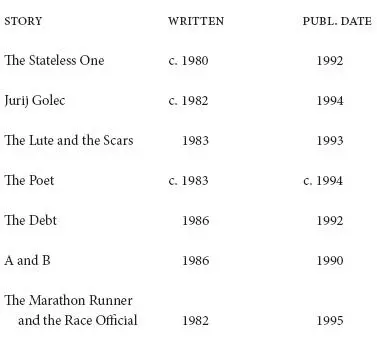

For an overview of the complicated genesis of the stories in this volume, the following table has been assembled from the original notes provided in the Serbian edition.

Readers will perhaps find it useful to stay attuned, while immersed in these stories, to conceptions of “home,” to various ways of embodying and depicting the “creative life,” and to the corrosive effects of dystopian dictatorships. The stories do at times have a lyricism that approaches the inimitable writing in the stories of Early Sorrows: For Children and Sensitive Readers ; they are, on the other hand, nowhere near as bloody as, and by and large not as harrowing as, the stupendous component tales of A Tomb for Boris Davidovich . They have enough of the virtues of these other story collections to elicit a strong reaction from readers, however, and they also read like “vintage Kiš”: to wit, the compression, the enumeration, the poignant detail, and the restlessly conversational language. The stories also offer us a chance to embrace a more fully Yugoslav, or Serbian, Kiš. The deep affection for Ivo Andrić and, metaphorically, the acknowledgement of the author’s own set of “debts,” is every bit as much “the real Kiš” as the cosmopolitan-ism — an artist’s search for authenticity and intuitive acceptance of diversity and intellectual and emotional (as opposed to political or ethnic) affinity — of “The Stateless One.” Likewise, the reflections on Yugoslav conditions in “The Lute and the Scars” and in this translator’s other favorite story in the collection, “The Poet,” are just as real as his many nonfiction pieces on French symbolism, Thomas Mann, and James Joyce. Finally, the looming presence of the USSR in so many of these stories reminds us that the political coloration of the backdrop to Kiš’s life changed, significantly, from black to red before his teenage years were out. This epic turn left its indelible marks on his intellectual biography, and it precipitated neatly into that most engaging of his plays, Night and Fog (see Absinthe: New European Writing 12 [2009]: 94–133).

* * *

These stories are deceptively complex, and their publication history is also complex. Therefore they received a good and necessary measure of critical attention and analysis as they were published — hence the indispensability of notes in and on the tales themselves. The original published notes to the stories can be found at the end of this volume.

The basis for the translations of the first six stories is the collection Lauta i ožiljci , edited by Mirjana Miočinovič and published by the Beogradski izdavački-grafički zavod (BIGZ) in Belgrade in 1994. For the provenance of the final story in this collection, “The Marathon Runner and the Race Official,” please see the notes at the end of the book.

I owe a debt of real thanks to the following friends for their help with various aspects of these translations: Predrag and Tamara Apić, Jessica Blissit, Sara Brown, Pascale Delpech, Ken Goldwasser, Bea and Wolfgang Klotz, John McLaughlin, Dragan Miljković, Mirjana Miočinović, Jeff Pennington, Dan Shea, Predrag Stokić, Aleksandar Štulhofer, Verena Theile, Gary Totten, and Milo Yelesiyevich. From books and encouragement to food, friendship, and fine points of vocabulary, these wonderful people have made bringing stories by Kiš to an anglophone audience into a very satisfying adventure.

This book is dedicated to the memory of Murlin Croucher. He was a mentor to many of us in the field of East European and Russian studies, an accomplished librarian, a universal wit and seeker, one pug-crazy dude, a lover of great literature wherever it was to be found, and my friend since 1987. Requiescat in pacem .

JOHN K. COX, 2012

NOTES TO THE ORIGINAL EDITION

Original Notes

These explanatory notes, a kind of critical apparatus for the individual stories in this collection, were written and first published by Mirjana Miočinović. The vast majority of them have been translated from the first edition of Lauta i ožiljci (published in 1994 by BIGZ in Beograd). There are four exceptions to this attribution. The last sentence in the entry for “The Lute and the Scars” and the final three paragraphs of the entry for “The Poet” are additions taken from the 1995 edition of Skladište . In the notes to “The Debt,” the comparative material on Eugène Ionesco is also from Skladište . The entire entry for “The Marathon Runner and the Race Official,” like the beginning and end of the story itself, was taken from the subsequently published French and German editions of the story, since I have not yet seen a Serbian edition. — JKC

General Remarks

The stories from Kiš’s literary estate entitled “The Stateless One,” “Jurij Golec,” “The Lute and the Scars,” “The Poet,” and “The Debt,” all of which we are bringing out in this volume, originated in the years between 1980 and 1986, connected more or less directly with the book The Encyclopedia of the Dead . We have supplemented these with the short two-part prose piece “A and B,” which in manuscript form had no title. Although it does not seem to fit the definition of “short fiction,” it does function in a metaphoric (and metonymic) way in relation to the larger body of Kiš’s work in prose: hence its place in this collection, and its position at the end, as a sort of “lyric epilogue.”

The stories “Jurij Golec” and “The Poet” are being published here for the first time. The others have already been published in this order: “A and B” in the book Život, literatura (Svjetlost, Sarajevo, 1990); “The Stateless One” in Srpski književni glasnik (1992, vol. 1); “The Debt” in Književne novine (1992, pp. 850–851); and “The Lute and the Scars” in Nedeljna borba (April 30–May 5, 1993).

In giving to this book the title The Lute and the Scars , we were guided by the fact that Kiš named two of his three collections of stories after one of the collected tales themselves; he did so less because of the story’s privileged position in its collection than because of the ability of the title itself to bring thematic unity to the other stories. It seemed to us that we could accomplish something similar with this title, in addition to enjoying its inherently paradoxical quality.

The Stateless One

The story “The Stateless One,” which comes down to us in “in-complete and imperfect” form, was inspired by the life of Ödön von Horváth. It will not be difficult for the reader to comprehend the reasons for Kiš’s interest in this “Central European fate” that ended in such a bizarre manner on the Champs-Élysées on the eve of the Second World War: Ödön von Horváth died on June 1, 1938, during a storm that descended abruptly on Paris, obliterating trees and sweeping away everything in its path. A heavy branch took Ödön von Horváth’s life, right in front of the doors to the Théâtre Marigny. He had arrived in Paris after an encounter with a “premium fortune-teller” in Amsterdam, who had prophesied that an event awaited him in the French capital that would fundamentally alter his life! (It is also easy to recognize the figure of an unnamed poet who plays an indirect but important role in this story: Endre Ady, whose life and literary fate was intertwined in similar ways with those of both Horváth and Kiš. In this sense, “The Stateless One” is in some of its passages a condensed replica of parts of Kiš’s story “An Excursion to Paris,” which dates from 1959 and was dedicated to Ady.)

Читать дальше