Isabelle began to straighten the papers on her desk. “Deputy Kerry here, from the Sheriff’s Department, will take you home in his police car. We’ll phone your parents to let them know.”

I started to cry. I broke and sobbed.

“Put the handcuffs on her,” said Isabelle to the deputy.

The deputy gave us all a pitiful look. “I’m sure that’s really not necessary, ma’am.”

“Put them on her and march her right out the front door. We need this as an example to the others.”

“All right, I guess,” he said, shrugging. He turned toward me. “You are under arrest. Put your hands behind your back.”

I was still crying, wiping my nose with the heels of my hands. I had no Kleenex, and no one would offer me one.

“Wait a minute,” I mumbled, and made some final attempt to clear my face of snot, then stood, turned, and thrust my hands back toward the deputy, who had unfastened his handcuffs from his belt. They were cold and stiff, adjusted tight for my thin wrists. These are the hands that had taken money, the cuffs seemed to say, and we are going to seize them, take them out of commission, chop them off. “Oh, no,” I moaned.

I was marched down the stairs and out through the front entrance, the deputy leading the way, grasping my elbow, and carrying my fallen straw hat, though it was Park Property. I was still wearing my cashier’s uniform — Hello My Name Is Benoîte-Marie — and I was trying to hold back my tears by breathing them into my sinuses. It was four in the afternoon, and the heat of the day had gathered itself thickly, even as the sun — a hot blister of bone — had begun its descent.

“Oh, my god!” I heard Sheryl, at the left front register, gasp behind me.

“What happened?” asked Debbie.

“What’s going on?” queried several Visitors to the Park, as we passed them standing in line. The loudspeakers played the Storyland theme song — now a bunch of oom-pah-pahs gone grim, like the end of La Traviata . Deputy Kerry marched me out in front of him, a light grip on my upper arm, and steered me straight across Storyland’s bright, sunny parking lot, to the back, where his car was parked. In the side of my vision I could see Sils in her stainless-steel tiara and sateen dress, pressed to the wrought-iron fence next to where her Pumpkin Coach toured. She called my name, then kept calling it, but I refused to turn. I was ugly and embarrassed; there was snot dripping down into my mouth and I couldn’t stop it. I didn’t want anyone else to see me. I didn’t want her to see. I twisted my neck and tried to wipe my nose on my shoulder, but I couldn’t do it.

The entire way back to Horsehearts — me in the back, Deputy Kerry in the front — Deputy Kerry said scarcely a word. He drove steadily down the lake road, past the tee-pee-shaped gift shops selling their fake Indian trinkets, past the turquoise motels all clutched to the lakeshore as if they were contemplating hurling themselves in. What would it matter? Especially in the long winter when the world abandoned them anyway. My head was full of carcasses and ghosts.

Deputy Kerry received a call over his radio, and he picked up the mouthpiece and spoke into it. It reminded me of riding with Humphrey in his cab; only this was the sarcastic, perverted version. How much more complicated it was for me, just me, to get a guy to drive me home from the lake. See what great lengths I had to go to! See how much ingenuity and nerve! Ho-ho! Sils had it easy. All she had to do was smile. I had to steal and weep and take on the law.

“Where do you live?” asked Deputy Kerry as we neared the chipping, weather-beaten old Chamber of Commerce sign that read, tragicomically, Entering Horsehearts: Village of the Future. It seemed strange that Deputy Kerry was only asking me this now, where I lived. What if I’d said, “Oh, didn’t they tell you? I live in Washington, D.C.!”

“Fish Glen Road,” I said. “Three thirty-six.”

“Oh, over there,” he said cryptically, and took a left at the next light.

My parents were on the front porch when we pulled up. To my dim and watery eyes, they looked faraway, two pink and furious figurines, and I realized, slowing up in front of the house, swollen-faced and handcuffed, that I didn’t know my parents well enough to be doing this to them, inflicting such an episode upon their lives. I realized that it was harder to endure the wrath and disappointment of people who’ve been kept from you, and from whom you’ve kept yourself, than it was to endure it from the people whom you knew best. All my stern upbringing was there waiting for me on the porch, its unhappy administrators waiting to administer something final and more — or perhaps, in their failure, to resign altogether, to take their leave of sternness, of administration, of me.

My mother stood up from the porch glider on which she’d been sitting, rocking herself back and forth with one foot, the other foot tucked up under her, her arms folded across her chest, her expression stricken and tight. My father turned from where he’d been gazing out into the mountains, rethinking his forestry degree, perhaps, or humming the most tragic Brahms he knew, or once again lamenting the snowmobiles that had wrecked the local wildlife, causing deer, now inured to the sound of motors, to dash out onto the highway and be killed. Perhaps he was making a list of all the ways your children could break your heart. He was not one to let you know what he was thinking, but he let you watch him think it, let you watch him stare into the air in which he constructed his worries and ideas, his eyes transfixed, his lips folded in. Now he turned to look at me, and the sheer height of him, even at that distance, filled me with remorse.

Deputy Kerry unlocked my handcuffs by the car but still clutched my elbow, pushing me along in front of him like a little cart. It was a long march during which I understood that, for all the unusualness in their lives, all my parents had ever wanted was to be average, normal, useful, ordinary. They could not bear the full force and chaos of their own eccentricity, could not bear the full life of it, the complete course, all the stuff and ramifications. To see something out of line in their own children must have reminded them of all that they were and could not hide from. It must have reminded them of the deep and sorrowful loneliness of themselves, which they had tried so desperately not to suffer.

Deputy Kerry handed me my hat.

“Go to your room,” my mother said coldly, and I stepped obediently into the house, staring down at my own steps as I took them, like a cartoon of a shamed person.

“Whoa,” said Claude, from inside the kitchen, seeing me. He was making a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. “What did you do ?” he asked.

“Just — shush,” I said miserably. I went into my room and flopped on my bed. I dashed the straw hat to the floor.

Claude came to the bedroom doorway. He bit into his sandwich. “Don’t worry,” he said with his mouth full. “I’ll spy for you; I’ll let you know what’s going on. I can check it all out from the front porch.”

“Great,” I said indifferently.

LaRoue came up from the cellar. “Tsk, tsk,” she said at my doorway. And then added, more consolingly, “Don’t worry.” She looked sorry for me, for the first time in her life. “Don’t worry. I heard them talking. They’ve decided not to yell.”

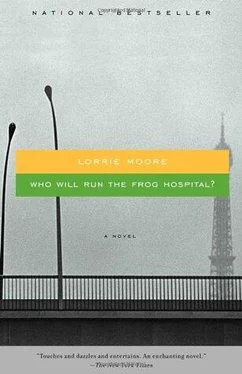

What they’d decided to do was to send me to church camp for the rest of the summer. They told me this after they’d thanked Deputy Kerry and shaken his hand (for a job well done?), and after they’d suddenly, briefly entertained a visit from Frank Morenton himself, who, Claude later told me, came flying up in his white convertible, leaping out to apologize to my parents for the public display at Storyland. He was also bearing my rope purse, which I had left at the Lakeside entrance. (How strange to imagine him with my purse!) “Let’s keep this whole thing with your daughter just between us. Here, this belongs to her.” He thrust the purse at my mother. “The park’s a nice family place,” he added. “I’m getting to be an old man. I’ve seen a lot. I came to this country with no money, and I worked too hard now to have my efforts be the site of scandal and commotion. I believe in America.” I was being treated with the same anxious hands as the Lost Mine crash. I was the Lost Mine crash. I was the same thing. All that is mine won’t be lost .

Читать дальше