I found a blogger criticizing the grammar of Tzvi’s use of the phrase “moving frame of references.”

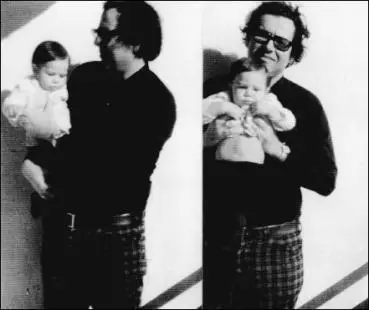

I found two photos — one in profile, one head-on, like mug shots — of a Tzvi-like man in plaid pants, standing on a balcony, holding a baby of indeterminate gender.

I found a geologic formation called the GalChen fach.

And I learned, from a purple Finnish Web page that began tinnily blasting a Mendelssohn dirge, that Tzvi Gal-Chen — most noted for his mesoscale work on downbursts and for his advances in single-Doppler radar research — had died of a sudden heart attack in October of 1994, at the relatively young age of fifty-three.

Then I noticed that next to Tzvi’s name in that roster of the Royal Academy of Meteorology, there was a pale gray asterisk.

I reloaded and reread and reconsidered the pages.

38. Very normal conversation

If one wishes to be a true scientist — an explorer not in search of what one desires to be true but rather in search of whatever truth there is — then one must be willing to accept, to engage, even to pursue further the most unwelcome and confounding data. One must be willing to make discoveries that shatter one’s most deeply held beliefs. Maybe it turns out that Earth is not the center of the universe. Or that monkeys are our relatives. Maybe we discover that a man is not an expert on himself, or maybe it turns out that we’ve been speaking to the dead.

A true scientist knows to explore, not dismiss, these uninvited discoveries.

So I wrote back to Tzvi, saying that I had recently received the impression that he was not alive.

“Oh. Yes. That is true, in most senses,” he replied without subject heading.

I felt a breeze then, just very locally, a microclimate, like what happens in a movie when a ghost floats by. “Then why, or rather how, or rather from where are you writing to me? And to Harvey too?”

Tzvi wrote back: “If you’ll remember, I didn’t initiate contact. All I did was respond. I guess it was flattering when Harvey called me ‘the mesoscale hero of the millennium.’ So maybe I answered just out of curiosity. Or loneliness. But really I think it simply seemed like the proper thing to do. He wrote, and so I replied, as he obviously wanted me to.”

Pressing Tzvi on the issue of his apparent death — that didn’t seem like the proper thing to do. But those two photos, in mug-shot form … and all the concordances … the retrievals work… so I found myself typing from my heart: “Is it as if in some worlds you’re alive, and in some worlds you’re not? Is that what your retrievals work really is: not between reality and models, but between actual worlds?”

“How,” he responded, “did you and Harvey come to be interested in my work in the first place?”

“If you don’t already know, I promise to tell you one day. However, I suspect you do know. But can you tell me — is it that you’re not really dead? Are you just, for some reason, pretending?”

“I would say more your earlier guess. Do I sound dead to you? I wonder if I talk like a dead man. My daughter once came home from school very excited about some lecture — this was years ago, before I died, though just right before — and she said her English teacher had talked about what the dead sound like in Dante. This funny thing about Dante’s dead, which is that they know the past, and even the future, but they don’t know the present. About the present they have all these questions for Dante. And that somehow is what being alive is, to be suspended in the present, to be suspended in time. She seemed to feel this really meant something. That and also that the dead know themselves better than the living do. When Dante the pilgrim asks, Who are you? the souls are able to offer these very succinct, precise descriptions, without provisos. I’m the one who was seized by love. Or, I am the one who quenched the doubt in Caesar. Everything very settled, you know?”

When is talking about literature not an evasion of the real question at hand? Although a nice-enough evasion. Into an honest and information-bearing kind of distortion. Was I supposed to ask Tzvi, as a kind of extended shibboleth that could separate the living from the dead, who he was? Was that what he was indirectly trying to ask me to do? But why should I care whether he was alive or dead if my main issue was finding Rema? And wasn’t talking about literature also as straightforward an invitation to interpret his research as he could offer? Because I–I should admit — found my thoughts retreating to literature too. Retreating from what I’m not sure. I thought of the last of T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets , a poem I’d once been made to memorize, in which the Eliot character chances upon the ghost of Yeats in the firebombed streets of London; upon recognizing Yeats, Eliot says they are “too strange to each other for misunderstanding.” And the Eliot character says directly to Yeats’s ghost, “The wonder that I feel is easy, Yet ease is the cause of wonder. Therefore speak: / I may not comprehend, may not remember.” Perhaps the simplest interpretation of this starchy turn of my thoughts would be that I thought of Tzvi as of a dead master? One with whom I felt strangely at ease? Or that I should just ask Tzvi to speak and nothing more? And as I sat in that darkness, a cluster of competing hypotheses came to me as I thought how to proceed:

maybe Tzvi wasn’t dead at all (or, implausibly, I was)

or maybe this was some mechanical residue of Tzvi, some part of himself translated into software of some kind

or maybe he was dead inasmuch as I could understand the situation, but his death was a matter of perspective, of frames of reference, or a frame of references

or maybe Tzvi was somehow Rema, since Rema had for so long pretended to be Tzvi

And none of these hypotheses dissuaded me from the belief that Tzvi could help me in my search, and so I resolved to ask him about Rema directly.

39. Conversation interrupted

But something clouded over my handheld electronic’s moonlight glow, and I turned to see what, and although my pupils’ contraction near blinded me, I made out the silhouette of the simulacrum. Her blotting out of screen glow made me think about the powder on sticks of chewing gum, then the powder in urns, and then gunpowder, and then the Chinese, and then fireworks, and the feeling was of my mind tripping along an infinitely winding and meaningless path.

“I had a nightmare,” she said, her voice drawing my mind back to a starting point, “that I was in bed, and I reached my arm out to you, and you weren’t there. And then I woke up and it was true.” She was leaning over me; I think she was trying to read from my screen. But Tzvi Gal-Chen was for me, not her. Even if he was her, he wasn’t this her. Or really just: I had a lot to think over.

I turned the screen off.

We were left in the dark, amidst all that velvet, and unaware of the location of the dog.

“Are you writing,” I heard her say, “or are you reading? Or, what are you doing? What are you doing awake? Now? Out here?”

Her voice in the dark, so familiar — it was almost as if Rema was actually there with me, in the absence of luminosity, and maybe she really was there, paying me a visitation. Maybe it was, very briefly, Rema. But like a faithless Orpheus I turned the light — my BlackBerry screen, that is — back on again, to verify. And despite the familiar hip, despite the undershirt, it wasn’t Rema.

“Do you not miss sleeping with me?” she breathed into the blue glow. “It is weird to me. I am no longer even an object of your desire?”

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу