Then Magda said, “I should have thought — he also knows the American. I should have thought of that connection, that you know someone in common. Do you want anything? I’m going to bed now.”

She believed I didn’t love dogs, but her dog came and slept in the bed with me that night.

28. What would Tzvi Gal-Chen do?

I really do like gentle dogs. And when I petted the velvety crown of Killer’s head the next morning, when I lifted one of her silken ears and held it like fine cloth between my fingers, she then lifted her gaze to me, which re-reminded me why I suspect people love dogs so passionately, for that loyal devotion of theirs that manages to be simultaneously easy and profound. Or at least their love appears to be like that even if only because I so desperately want to believe in such a love.

My pants were draped over a chair near the bed; the little nugget of paper upon which I’d written my notes had fallen to the floor. It looked like ordinary trash. I felt ashamed about a certain sort of slapdashness converging upon my mission. I put on the foreign pants. I picked up my crumpled note. I sat myself with proper posture at the desk. Killer arranged herself in a curl near my feet. And I uncrumpled:

Unnamed dog?

Anatole?

Royal Academy?

Rema’s husband?

Tzvi Gal-Chen?

Now there were Lola and the dog man to consider as well. There might be duplicates, though: the dog man might be Anatole, Lola might be Tzvi Gal-Chen. And maybe Tzvi, Lola, and the Royal Academy should all be one category. Or Tzvi and Lola just subcategories of the Royal Academy. And what of Harvey?

But this “system,” in terms of action, was getting me nowhere. I felt acutely that I didn’t even have, like, say, Harrison Ford in Frantic , a suitcase to rummage through. My life — so much less compelling, so much less organized, than even a movie. But I knew that was a uselessly vain thought, utterly beside the point, an influence of grogginess, and I did have this lead with Lola at the Academy, surely that would turn up something, sometime, and yet, here I was, indefinitely doing nothing in pursuit of Rema. That’s when I heard in my mind — and I knew it was just in my mind — a Rema voice giggle-accuse-whisper: What would Tzvi Gal-Chen do?

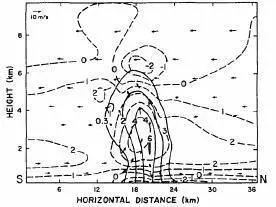

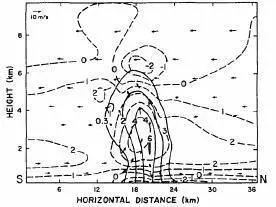

I resolved to look again more closely at Tzvi’s research paper, “A Theory for the Retrievals,” a work that claimed to be retrieving “thermodynamic variables from within deep convective clouds,” but that I suspected — or hoped — might be about quite a bit more. As I combed through the pages a small Rema memory came to me: I had once taken her to a performance of Hamlet , but the antique English of it had meant that she’d hardly followed a word, so it was less than a spectacular evening, and I’d apologized to her for not having thought of how the language would be difficult, but said that maybe it was kind of appropriate to the play, since the play was about, I said, what happens when you grossly overestimate what thinking can accomplish, and she’d said, no, really the play’s about the long influence of dead fathers, that’s how I like to think about it, she said. It just came to me, our little trades, her small indignancies, and I missed her so acutely. Regardless, Tzvi’s paper, despite the difficulty of the language, did indeed reveal to me what was quite compellingly a reference to my situation with Rema. It argued for the validity of introducing into atmospheric models two types of errors: white noise, which referred to errors “on all resolvable scales,” and blue noise, which referred exclusively to “errors on the smallest resolvable scales.” These errors, he argued, enhanced “the realism of retrieved fields.”

Did Tzvi know all about those “errors on the smallest resolvable scales” that characterized the doppelganger? Did he know how this related to retrieval? Certainly he knew about how Crays working in tandem could solve problems of increasing magnitude. So arguably it was as if I was a Cray, and he was a Cray, and … well why, I thought, shouldn’t I turn to Tzvi for help?

That image from the first Gal-Chen paper I’d seen, back in the library: in addition to reminding me of Rema, it also looked to me like a lonely man, in an alien landscape, glancing back over his shoulder as if to ask something of someone whom he was not sure was there.

“Maybe I will write to Tzvi,” I said to gentle Killer, who did not seem to disapprove. “Maybe I need to make progress on the mesoscale, that is, the human scale.” And so, sitting there in my mother-in-law’s room, a mother-in-law I hardly knew and who hardly knew me (and who had been given the wrong clues for getting to know me), I turned my BlackBerry on, switched it to silent, and tried to be professional, direct, and sincerely warm at once. After thanking Tzvi for his correspondence with Harvey, I wrote to him about: the erroneous Rema, wanting to retrieve my own Rema, the inexplicable intrusion of dogs into my life, my most recent contact with the Royal Academy of Meteorology. Then I simply asked, making reference to his work that had wisely directed me to Buenos Aires in the first place, if he had any suggestions for how I might progress in my attempts at retrieval.

29. A mysterious misrepresentation

Dear Leo Liebenstein, MD:

I’m sorry. I suspect this is kind of my fault. I don’t actually know Harvey. There’s been some confusion. I really am sorry. And I’m sorry to hear about your wife. Unfortunately I don’t know anything about her. Or her whereabouts. Again I’m sorry. I regret any confusion I’ve caused. For a few reasons none of which you should take personally I don’t think I’ll write to you about this again

.

This reply arrived almost immediately.

I did think, for a moment, that maybe Tzvi had taken Rema. That, though, was just indignation speaking.

A better explanation for the cold reply: maybe Tzvi, like me, thought he had to work all alone because he didn’t know if he could trust in me — after all, when he first received that note from me I was nothing to him but an e-mail address, and anyone can be behind an e-mail address, regardless of who appears to be behind it. (Years after my mother died, I would still receive mail addressed to her and occasionally I would answer her mail; once I went and picked up her glasses prescription.) So I can understand Tzvi’s mysterious misrepresentation of himself and his knowledge — he couldn’t be sure with whom he was communicating. And he knew what I didn’t then know, which was that his own position was ontologically dubious. So he was experiencing, in a sense, an Initial Value Problem in response to having received a communication from me; he didn’t know whether I was a parameter he might safely rely on, in order to accurately infer forward to a forecast of the truth, to reliable predictions of possible futures. Perhaps, all alone as he was then, as he maintained himself, working in isolation for the Royal Academy, he may have worried that he was, proverbially, “going mad.”

I was alone too. If only Killer — very little white shows in dog eyes, so it’s more difficult to tell where they’re looking — could have offered me a second opinion, a second interpretation of the situation. Yes, retrospectively I can certainly understand Tzvi’s retreat from intimacy as a manifestation of his anxiety, but in the chill of the moment I reacted less pacifically. Feeling that I had been condescended to, I responded immediately with:

Dr. Gal-Chen:

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу