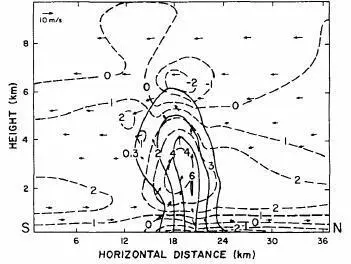

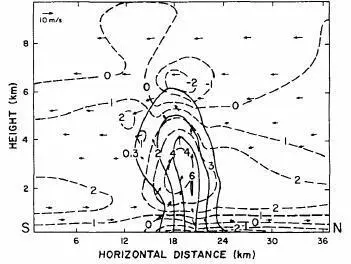

FIG. 3. Vertical y-z cross section at 90 min. at X = 14.25 km through the model storm showing the rainwater mixing ratio contours (g kg −1, solid), the velocity vectors in the plane, and the potential temperature change from the initial base state (°C, dashed). South is to left and north to right. Wind speed proportional to vector length; areas void of vectors indicate very little flow in this plane

.

Anyway, I would be curious to know what this image recalls to others.

After an uncertain length of time spent staring — I heard footsteps in a nearby aisle — I flipped back a few thin pages to the cover page of the article that contained the arresting image.

The first author: Tzvi Gal-Chen.

The paper was originally presented at a conference in Buenos Aires.

Buenos Aires being Rema’s hometown.

And Tzvi Gal-Chen being Tzvi Gal-Chen.

And the article was about retrieval. Specifically: “Retrieval of Thermodynamic Variables Within Deep Convective Clouds: Experiments in Three Dimensions.”

My pulse rose; my fingers went cold. Then the light went out; I crawled along the shelving to turn it back on. I know the ordinary often masquerades as the extraordinary, that if you put thirty people together in a room, the likelihood that two have the same birthday is over ninety percent, that when you learn a new word and it then seems suddenly ever present it is only because you have just begun to notice what was there all along. (This once happened to me with the word cathect . Also Rosicrucian.) Maybe that’s all that this find of mine was. For all I know, maybe Tzvi GalChen and Buenos Aires were both already pervasive terms and I’d simply stumbled across two examples of Baader-Meinhof phenomenon. But the fitting together of so many elements — sometimes that really happens, a stray orange peel, a necklace, and a certain joke about iceberg lettuce once converged to reveal a girlfriend’s infidelity — convinced me that I was perceiving something real, that I was not myself in any way cracked, that only my world suddenly was.

So I would go to Buenos Aires. I’d return to Rema’s beginning, a place I’d never been. Why Rema might have gone south — or if she’d been taken there, or if she was still there, and what her connection to Tzvi Gal-Chen might or might not be — I had no idea. But it was that afternoon in the library, in those dusty aisles with the lights always threatening to turn off, when I had only the faintest of knowledge, that I knew with the most certainty what to do next. Like how it is on the foggiest of nights that radio signals come through most clearly and from seemingly impossible distances.

13. We exchange words, not pleasures

The dog lover did not take it well that night over dinner — a heap of lentils and bacon and spinach with a facedown sunny-side-up egg on top, I always loved our messy pile-on meals — when I said that I’d be leaving for an indefinite length of time. She asked me why I was leaving; I said because something had changed and I just needed to get away. She asked what did I mean by leaving and I realized I didn’t quite know, so I decided to be cautious and say that I was taking a personal vacation. Those phrases, something has changed, just need to get away, personal vacation , were not really my words but TV words, movie words, pollen in the air. Not even aliens from within me, but aliens from without. More luggage. She: leaning on an elbow, holding her fork aloft and still, with nothing on it, asking, What did I mean by “changed”? Me saying I wasn’t quite sure what I meant, that I hadn’t found words for it yet. She: asking, Where, exactly, was I going? Me telling her that as nice a person as she seemed to be, I didn’t really feel comfortable telling her. “Not yet,” I clarified. “But maybe never.”

She pressed the empty tines of her fork against her bottom lip. Then she set her fork down. She was very sober, and very calm, very unlike Rema.

“Are you seeing someone?” she then asked, which struck me as funny, because there are so few people in the world that I like even a little bit.

I may have cracked a nervous smile. I shook my head no.

“Are you playing a joke?” she asked.

Again I shook my head.

“Is this related to, are you relating to, um, yesterday?” she asked.

“I don’t think so,” I said, which was as honest an answer as I knew.

“Or Harvey?”

“I don’t think so,” I said again.

“I don’t understand,” she said, putting down her fork, which, touching the plate, sounded a gentle reverberating ting like a creeping chill. Her tines then disappeared into the lentils.

“I don’t understand either,” I said, and I also put down my fork, as a gesture of respect, even though I was still hungry, and even a little bit happy, since I had a kind of plan. I could almost see the pulley system — something made of thick gray rope and metal coated over with a chipping white paint — by which my life’s getting better would make this other Rema’s life worse, and just having that thought moved the ropes back against me, for her.

We were quiet for a little while. I looked at her and then when I saw her look at me I looked back away, down at my plate. The lentil dish we were eating that night was made with tarragon, which I always forget smells like licorice until I close my eyes and ask myself why I have an image of myself lying under a patchwork quilt and coughing. I wonder if Rema, or her doppelganger for that matter, experiences silence (or tarragon) the same way I do; for me silence is like a humid swelling of scents, originless clicks, phantom elbow pains, a puff of air near the eyes, a sense of grass pushing up through the earth somewhere, or everywhere at once. I’ve never asked Rema about this.

The simulacrum scooted her chair back, went to sit on the sofa; the russet dog joined her. “You are trying,” she said, not actually looking at me, “to make me say I love you and beg you to sleep with me, but I am not here to perform for you, you can go through your preoccupations on your own and talk to me on the other side of them.”

I said nothing. I just looked at her. There on the sofa, unnamed pup at her side, she was running her fingers perpendicular to the wale of her corduroy skirt. Then parallel to the wale. Then perpendicular. Just by watching, I could feel the grain of the fabric, which made me think of the grooves that make our fingerprints, which made me think of the fingerprinty look of that meteorological image in Tzvi Gal-Chen’s paper, which made me think of the myth of fingerprints, of one of the few things that I remember my father telling me, that really all fingerprints were the same. And snowflakes? I’d asked. And snowflakes, he’d answered.

The russet dog nose-sighed, turned a tired gaze toward me.

“Is it your plan,” the simulacrum said, “to say nothing? You’re not really going to leave. You’re just imitating a drama of me, a show I might put on.”

Despite a certain type of certainty, I remained very unsure as to how conscious this woman was of being an impostor, or perhaps an alternate. As far as I knew she might be like an understudy who’s been lied to and believes that the show goes on only on Tuesdays, and that she is really the only star. Maybe this woman also felt that something was somehow wrong, that she was with the wrong Leo; maybe she, like me, could not articulate precisely what was wrong, but unlike me she did not trust her feeling. Maybe at some point in time, in some place, an other Rema and an other Leo were living together very happily in a whole other parallel possible world. A world not unlike the ones Harvey so often talked about. It was possible.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу