Sarah Hall - The Electric Michelangelo

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Sarah Hall - The Electric Michelangelo» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Faber and Faber, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Electric Michelangelo

- Автор:

- Издательство:Faber and Faber

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Electric Michelangelo: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Electric Michelangelo»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Electric Michelangelo — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Electric Michelangelo», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

— They want rampant lions and the St Andrew’s cross, no doubt, or Rangers colours, eh?

Cy remembered he had said this somewhat smugly, thinking himself capable of a certain amount of discerning and prediction after a year’s apprenticeship. The Scots were singing a song about virgins in Inverness, happy to have arrived at last on their annual holiday. Riley had been walking away from them but at this remark he stopped and turned back to Cy.

— No. No, lad. I paint hearts. And I paint souls. That’s what I do.

Back then it had seemed a ridiculous thing to say. Too much like the great Eliot Riley on a flight of fancy, getting wordy and profound, trying to make Cy feel like the village idiot again. But the comment stuck with Cy for some reason, perhaps because it sounded good, the sound of the words themselves had a note of quiet percussion to them, unlike Riley’s usual loud and boasting bluff, or perhaps just because aspects of the man were like burdock that got on to you and sank in. And Cy remembered what he said that afternoon. And then one day, years later and half way across the Atlantic Ocean, with a country lost from sight behind him, an old life scuppered and a new one about to be launched, it became true.

PART II

Babylon in Brooklyn

Coney Island lay colourful and flashing and ready for revelry under a dull coat of inclement weather. It was a slow day, with pedestrian business responding to the greyish skies overhead, the glitz and hum of the parks seeming all the more stark and garish for the lack of visitors to justify their existence. The mazed walkways, the decorated blinking gateways and turnstiles into the fairgrounds were almost deserted, the rides and the shows were quiet but for their own character exertion. On days like this the whole place gave the gimcrackery impression of a bright and showy and useless thing, or a clown vigorously juggling for empty rows of seating in a circus tent, primed and pathetic and somehow futile. Coney’s beach could seem as dire against the damp and drizzle as it could be inviting on days of clear sunshine. The sand looked logged with water, heavy and turgid. The Wonder Wheel in Luna Park was turning through the mist, providing a view of nothing but cloud for the few in its carriage seats, perhaps a stray patch of the city in the distance where there was an opening in the fog. For the past half hour Cy had been chatting with the hotdog vendor opposite his booth in the alley, smoking cigarettes, passing the time under the rattling, dripping awning of the meat stand. The grease-aproned man was stirring up his sauerkraut with a spoon and complaining halfheartedly about trade as if for something to do rather than with earnest concern.

— Half my stock will go bad if I can’t boil it by the week’s end. I’m going to have to ditch it with the fishermen for bait, the fish really go for the fat see, chicken bones too, go figure, or I end up eating fifty a day myself and I ain’t that hard a worker. Nobody will put up with old meat these days, not that I’d serve it mind with those sanitation chumps breathing down my neck. Listen, you come back when you leave and take a box of bratwurst home with you. Hate to see it go to waste. You gonna take off, board up early?

— No, no. I’ll hold on a spell. Never know, do you?

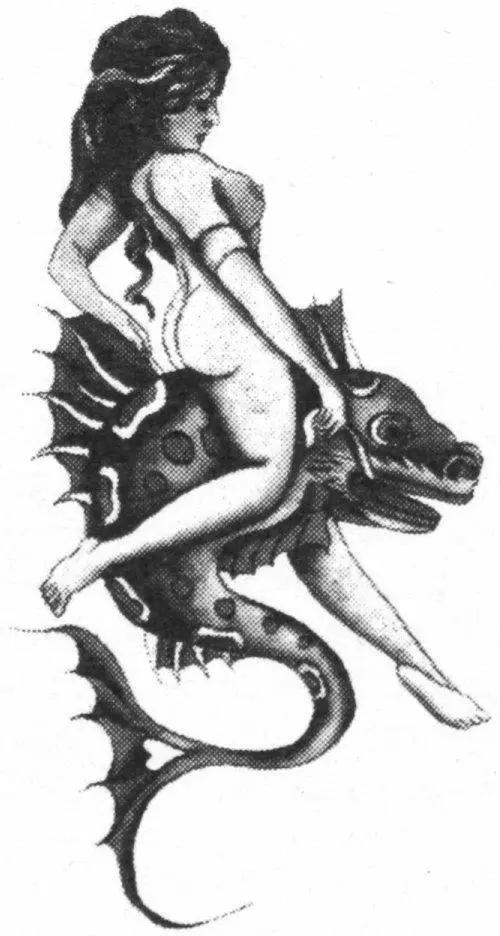

— Nope. Never know what they’ll hand you down here. Hey, you gonna do my Rosie over sometime? Her tits are beginning to fade. Gotta have those red tits! Old Grady Feltz did a good job on her for one of them navy yard boxer guys, and blind in the eye and wearing that damn patch and all, but she’s beginning to go a little at the chest. Her and the wife, I love my wife but you know what I mean. She’s my lucky charm, my Rosie, got to keep her looking sweet and shiny, right?

— Come on by later if there’s nothing doing.

Some of the other tattoo artists did not bother opening on wet days at Coney. For Cy it was a different matter — had he closed up shop in Morecambe on every poor day he would have lost two-thirds of his business or more. Besides, there were those who felt an urge to come to him on broody, overcast days, or the rain would pull them in off the boardwalk and beach to the inside venues past his place of work, and they might be struck with the inspiration to get tattooed. Sure enough two men were walking up the narrow avenue with caps turned slightly down against the first mention of rain coming in off the Atlantic and when they got to Cy’s booth they paused to look at the bright, fluttering walls of the small hut. The vendor gestured with an uncooked sausage to him that he had customers and better go. Cy ground out his cigarette under his heel and approached the men, his hands in his pockets, his stride long. And without a moment’s hesitation the brassy polished voice of his profession left his mouth.

— Grand day, gents. Seems this is fine English weather we’d be experiencing here. I knew it wouldn’t take too long for it to find me hiding in your great country. I suppose my old missus must have sent it as a present for our happy parting. What’ll it be for you? I can see you’re both men who know your minds, which means you know you want the best and you’ve found it. Your girls’ names with a red rose perhaps, in keeping with this fine English weather, eh? No better way to say you love ’em than their name on your shoulder. This one here’s a beauty. A prize-winner, I’d say, perfect as any from the King of England’s palace gardens, am I right? And since it’s my national weather day I’ll work you both for two dollars and the King’ll think you stole those roses right out of his garden from under his nose.

The patter of rain, the patter of the trade, it was as easy as that now, when he wanted it to be, when he switched to a higher gear in his brain. It was as easy as starting anew in another country and introducing himself as a brighter version of what he had been.

The men continued looking at the flash. A bulb was flickering on the sign festooning the doorway. Cy reached up and moved it in its hub and it calmed its erratic light. Underneath that was a painted sign that read ‘The Electric Michelangelo, Freehander, Antiseptic treatment, Crude Work Removal, No Tattoos under 18 years of age’. There was a picture of an artist’s palette with a paintbrush resting on it underneath the lettering. Cy’s hair was tied back with a piece of black ribbon, and in his left ear was a pearl, as if he were a character from another century. This was his life now. This was who he was.

One of the men seemed more serious than the other, examining the pictures lengthily while his pal chuckled at bare ladies and grinning, horned faces. Cy turned his attention to the first man.

— Sir, you look like a boxer to me, am I right about that? It’s in the shoulders, if you’ll pardon the interpretation. What do you say to a champion middleweight puncher right along your back and your name alongside it? What’s your name, sir?

— Eddie.

— Nothing fits on a man’s back better than his ability to fight, Eddie. That’s a talent to be proud of. That lets other men know the situation right off the bat. Repels the rivals. Keeps the public informed, you could consider it a service.

Eddie shook his head and started talking, softly, a little embarrassed.

— I’m not a boxer. Glass jaw, see. Do kinda like the Dodgers though. Gonna take my kid when he’s old enough. Been going since I was six. My old man took me, back then there was Dazzy Vance, that guy could put ’em past a hornet’s tail, had this funny little wait before he pitched. Sweetest right armer there ever was, my daddy used to say. Saw Ol’ Stubblebeard pitch back when he played, before he took to managing.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Electric Michelangelo»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Electric Michelangelo» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Electric Michelangelo» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.