Julia Fierro

Cutting Teeth

For

Justin,

my everything

and

Luca and Cecilia,

who taught me to love

and be loved

Parents are the bones on which children cut their teeth.

— PETER USTINOV

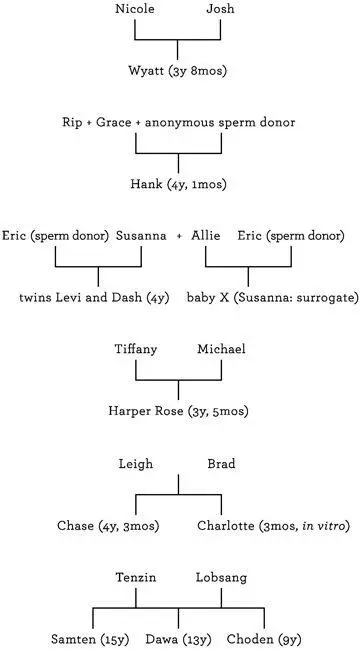

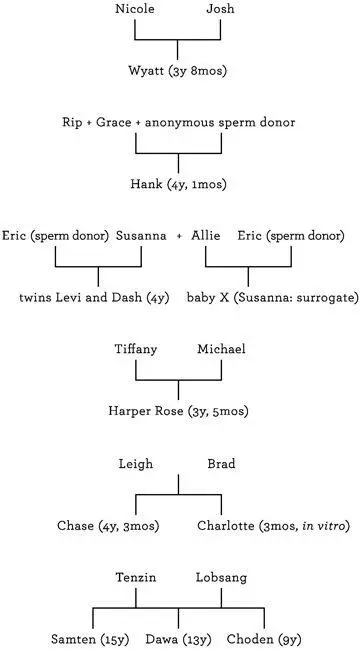

The playground washalf-empty, as it is most late-summer Thursdays in the Brooklyn neighborhoods where the young professionals live. Those who summer, who go in with one or two couples and rent a cottage on Fire Island or out East. Those who eat organic and buy green and practice hot yoga and are in treatment and who name their children, without a second thought, after Greek goddesses and dead poets.

Nicole pushed her almost-four-year-old son Wyatt on the swings, his cries of more more more fading, then rising as he swayed back and forth. Dusk was settling, the smoky veil that had hinted at danger for as long as Nicole could remember. The gloaming. The word still made her think of restless spirits and mistrustful things, the ghoulish witches in the dark woods of her childhood.

The sun ricocheted off the sunglasses of the mother standing next to her, the spinning spokes of the tricycles, the side doors of the cars squeezed up and down the block, and Nicole shielded her eyes with her hand. The fumes from the ice-cream truck idling on the corner scratched at her throat.

The little girl in the next swing coughed, and Nicole steeled herself. The child had a wet phlegmy cough, after all, not a dry raspy cough, which is what the Centers for Disease Control had listed as symptoms. Warning signs.

Relax, Nicole thought. It’s just a summer cold.

“Honey,” the girl’s mother said. “How do we cough?”

The little girl lifted her arm to her face and coughed in the direction of her elbow, all the while looking up at her mother, seeking her approval.

The mother smiled at Nicole with an apologetic shrug, and Nicole knew she was expected to commiserate.

She shook her head knowingly and pointed to Wyatt, still clad in his white karate uniform.

“I tell this guy the same thing. Every day.”

The woman smiled, relieved. “They make you so paranoid, you know? All those hand-washing ads.”

She was pretty, this fellow mother, and Nicole wished she had smoothed a little product into her own humidity-frizzed hair before leaving the house. Maybe some mascara to widen her tired eyes. As she gave Wyatt’s swing a big push, she felt the extra weight in her thighs jiggle.

She tried to swing Wyatt away from the little girl who continued to cough, a cough so productive Nicole thought she could see the miniscule drops of saliva flying toward Wyatt’s gaping mouth.

“Higher, higher, Mommy,” he yelled. “Up in the sky. I’m an airplane. I’m a superhero. I’m a pterodactyl. The fastest pterodactyl in the world. Watch what I do!”

“Oh-kay,” she said with a big exhale between syllables, “we have to go now.”

She gripped the chain of the swing and stopped him too abruptly. Wyatt nearly flew out of the seat.

“I’m sorry, sweetie,” she laughed. “Mommy’s so silly.”

“I don’t want to go. I want to stay.” His lower lip displayed a clownish quiver.

“I’m sorry. I really am. But we have to go, Mister.”

Nicole was sorry. Sorry she was ruining his afternoon and, perhaps, she thought with a growing panic, ruining his life by visiting the park because she was certain the little girl was very ill, certain that within a few hours, the girl would be shivering with fever in bed, a nasal swab sample on its way to the hospital lab. Because isn’t that what they said online, on the news, and in the handouts that had been given out at Wyatt’s preschool? That it hit fast and hard? That you woke with a sore throat in the morning and by nightfall had a high fever, cough, chills, vomiting? She knew the incubation rate, the statistics, the symptoms, and the percentage of children — healthy children, robust children (like her Wyatt) — who had died. At first, Nicole had tried to avoid the news. She had even considered, at her husband Josh’s prodding, disabling the wireless, shutting off the cable, but reminders were practically everywhere. In CNN’s top headlines and most popular online searches. The death toll, the latest CDC reports. The public-service commercials with that ridiculous rhyme, Know what to do about the flu. She had googled “flu” and “swine flu” and “h1n1” so many times that the little ads that popped up in the margins of her e-mail were all for antibacterial hand soaps and flu remedies. How to stay healthy. Ten ways to keep you and your family safe.

Then, after so many months spent fearing the flu, Nicole had spotted, just the night before, the paranoid chatter on urbanmama.com, the online mommy message board she browsed regularly. Post after post by mothers fretting over rumors that some computers were predicting the world might end? Josh had laughed at her that morning when she told him, then laughed again when she had tried to explain what a Web bot was, all of which she had learned via Wikipedia. Web bots were superpower computers that scanned the Internet for patterns, and many of their predictions—9/11, the market crash, Oklahoma City, bird flu — had come true. Josh had muttered something about overeducated women with too much time on their hands, ignoring her pleas for him to just google it !

Thank God they’d be away that weekend. What luck that she’d scheduled the playgroup’s Labor Day weekend trip to her parents’ house out on Long Island. When she had first read about the rumor that morning, what the moms on urbanmama.com were calling a potential “catastrophic event,” implying that it might take place that very weekend (Saturday night, to be exact), she had thought about canceling the playgroup’s three-day vacation out East. But it had been such a hassle to find a weekend that worked for all five parents in the Friday afternoon playgroup, and their significant others. The e-mailing and texting, scheduling and rescheduling had gone on for weeks until they had found a weekend when they were all free. Nicole knew that if she canceled, she’d ruffle many a feather. A few of the parents had even arranged to take off work the next day. She could already hear Tiffany, with her sanctimonious tone, “It’s just so cruel to disappoint the children, Nic. Don’t you think?”

Wyatt’s hands, white-knuckled, gripped the swing’s chains.

Nicole leaned over him and whispered, her lips close to his flushed cheek, “You want a treat?”

She tucked her fingers into the sweat-damp curls at the back of his neck. Sweet little boy sweat that smelled of apple juice and cut grass. She inhaled, wishing she could stop time and bottle the smell — bottle Wyatt even — because one day it would all be over. Wyatt would be a harsh-smelling hard-angled man. She and Josh would be old. Dead.

A plane passed overhead. A whoosh that built and built until it seemed to Nicole that a great big hand had unzipped the sky, and she looked around to see if anyone else had heard it, had felt it, as a warning of some kind. A prelude to disaster. There were a few mothers looking up, shielding their eyes with freshly manicured hands. Was it too low? Nicole wanted to ask; did they think it was suspicious? The engines were awfully loud, weren’t they? She snapped the rubber band on her wrist, an assignment from her therapist, pulling it farther away each time, the sting growing with each release. Nothing bad is happening, nothing bad is happening. She looked again at the sky to watch, to wait for the sign that all was clear, that it was just her ever-faulty interpretation she had, even as a child, doubted.

Читать дальше