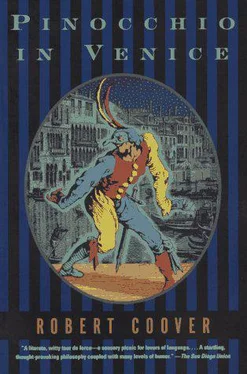

Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1997, Издательство: Grove Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Pinocchio in Venice

- Автор:

- Издательство:Grove Press

- Жанр:

- Год:1997

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Pinocchio in Venice: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Pinocchio in Venice»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Pinocchio in Venice — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Pinocchio in Venice», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"Ha Ha! Che brutta figura! Poor little cock's lost all his feathers!" exclaimed one.

"He's so light," laughed the other, "it's more like the feathers have lost their cock!"

That was his last bridge. Before that, how many, he doesn't know. He was in a kind of delirium. Fever probably. What's left of his flesh must be literally burning itself away. It was cold when he staggered out of the bedlam of that august temple gone suddenly berserk, colder than he'd remembered, and snow was being whipped about still in the sharp wind, obscuring the high bridge in front of the church, only meters away, his first obstacle, but he was on fire with terror, desire, and the hot flush of his infirmity, and the bitterness of the weather seemed only to invigorate him. Up the bridge he went and down, escaping and pursuing at the same time, hobbling to be sure, cracking and splintering and creaking with the cold, hacking and snorting, half blind, but on the move, his withered limbs at times outflung, tossed convulsively awry, to the casual onlooker appearing no doubt a bit whimsical and unstrung, but still clattering resolutely on down the narrow calle on the other side, feeling indeed like something of an athlete, a centenarian version of that spunky youngster who could leap ditches and hedgerows at a single bound, now with each lurching step making about as much progress laterally as forward perhaps, and having to improvise rather desperately at corners and bridges, but feeling that same exhilaration of the blood, that delicious conflict of pain and pleasure that characterizes a race well run, and keeping in mind all the while his noble goal — he will teach her! she will become his last great project! his pupil, his protégé, perhaps even his secretary, biographer, curator, and literary executrix! — as well as the more compelling images of a hot bath, a warm bed, clean sheets, and a pillowy blue hollow wherein to tuck his frostbitten nose.

Which was what, having no other guide, he had had to trust on that mad chase, following wherever it might lead, sniffing the crisp air for traces of her powdery warmth, her slept-in jeans, the tang of bubble gum and nail polish — and, at the crest of a short arching bridge, he was rewarded suddenly by a glimpse of azure blue, a distant flicker of startling color within the white blur, vanishing as quickly as seen, but which could only have been her sweater (had she taken off her windbreaker? was it a signal? a tease? was she walking backwards? he couldn't stop to think about this), and thereafter he seemed to see it more often, on a bridge, at the edge of a riva or the end of a little calle, fleeting and elusive as his famous last chapter, there and not there, yet drawing him on, though he couldn't be sure he saw it, saw anything for that matter, his vision, never the best, now hazed by icy tears and sweat and the crazy pounding of his heart in his temples and sinuses. So absorbed was he with the object of his pursuit that, as had often happened in the middle of books he was writing, he failed to notice the weariness, the physical and emotional exhaustion, that was rapidly overtaking him, overtaking him once and for all, his mind racing far ahead, abandoning his body, leaving it to drag along behind as best it could until it stopped. Which, inevitably, it did. Halfway up a bridge. He, who was very much afraid of the ridiculous, was then, with fearful ridicule, lifted laughingly to the other side. And stood for a time just where he was deposited, intent only on not adding to his indignity by falling over. It was not easy. Had anyone so much as sneezed nearby, it would have toppled him. And, straining thus to stay upright, he inadvertently pushed out a tiny gust of flatulence which escaped him like the shrill little peep of a wooden whistle.

"Ho! Thou wert a beautiful thought, and softly bodied forth!" declaimed a voice that seemed to come from the brick wall above him.

"Who is it that speaks so eloquently?"

"Not who is it, but what? It looks like a holdover from the last plague!"

"Or else something the boss might have had for lunch! Porca Madonna! If I had a stomach, I'd be throwing up!"

He was standing, he saw through his frozen tears, in front of a maskmaker's workshop, its entrance and windows lined with the painted faces of mythical creatures, wild animals, goblins and fairies, jesters, plague victims, suns and moons, bautas and moretas, death's heads, goddesses, chinless rustics, and bearded nobles. "Whatever it is, it's got more holes in it than a piece of cheese!" declared one of them, the pale pink-cheeked sun perhaps, a somber white-bearded Bacchus replying majestically: "Maybe it's a flute." "You mean, dearie," cooed an angel with cherry-red lips, "you don't know whether you should eat it or blow it — ?" The ancient scholar, feeling now the full weight of his folly, wished desperately to escape these japes, but could not, his father's infamous joke — "What brought you here, Geppetto my friend?" "My legs!" — no longer a joke. "If I had a body like that," scoffed a freckled face with a red hood and golden braids, "I'd sell it for a pegboard!" "If you had a body, cara mia," whispered a ghostly voice from behind an expressionless white mask with large hollow eyes, "you'd sell it for anything!" From behind the window, he could see, he was being watched by a glowering figure with a wild black beard like a scribble of India ink, making hasty sketches on a pad. "But what's that lump between his shoulders with the pump handle on it?" the empty snout of a camel posted in the doorway wanted to know, and: "Look from what pulpit comes the sermon!" jeered a grinning noseless skull.

Then suddenly they all fell silent. Even the distant scraping of shovels stopped and the wind died down. Nothing could be heard but the water in the canals, far away, timidly lapping wood and stone. "Who was it," thundered a deep ogrish voice from overhead, the very sound of which set the masks rattling on the wall with terror, "laid this turd at my doorway?" It was the maskmaker with his apron of black beard, smeared with paint and plaster, his roaring mouth big enough to bake buns in, and eyes so reddened by grappa they seemed to be lit from behind by a fire deep in his skull. "Who has made this inhuman mess?"

"It's — it's not my fault!" the old professor wheezed, indignant even in his indignity, bold even in his abject dismay.

"What? What — ?! It speaks?" bellowed the black-bearded giant, leaning closer and baring his horrible smoke-stained teeth. "Talking turds have been outlawed in Venice! Is this the work of a rival seeking to discredit me? Is this — what you say — dirty tricks?"

"Believe me, my — "

"Enough! Basta cosě!" roared the maskmaker, snatching him up by the scruff. "There's only one place for rubbish like you!" And holding him aloft with one mighty fist, from which the unhappy pilgrim dangled limp as a skinned eel, the bearded giant strode into the nearby campo and, much to the amusement of the passersby — "Ciao, Mangiano! What's this? One of your rejects?" "Madonna! What an obscenity!" — thrust him, up to his armpits, into this plastic-lined wastebin.

Where, with the filling up of the campo, he has become the popular target of insults and horseplay. Mothers show him off to bundled toddlers to make them laugh; little boys, when they're not chasing bedraggled and dying pigeons, pelt him with snowballs; teenagers with ghetto blasters hugged to their ears flip their cigarette butts at him. He is crowned with fruit peels, pink sports pages, and rancid boxes from fast-food joints, christened with the dregs from supermarket wine cartons. "Piů in alto che se va," the musicians are singing raucously and tunelessly at the other end of the square while testing out their equipment, "piů el culse mostra!" The higher one climbs, the more he exposes his behind: a sentiment so apposite to the old emeritus professor's present humiliation, he might suspect them of malice had they not been entertaining the passing crowds with all manner of rude scatological lyrics since they began setting up. To add mockery to the damage, pigeons use him as a perch and public restroom, which causes one of the musicians drifting by, a swarthy snubnosed character looking more like a thief than an entertainer, to remark loudly and histrionically that "Every beautiful rose — " he lingers over this image to draw the guffaws, his plastic features twisted into a set painful smile, his hands flowering about the old bespackled professor's head, "- eventually becomes an assmop!" And the others in the campo gleefully pick up the refrain: "Un strassacul! Un strassacul!" The caged visitor, ever an emotional, even irascible defender of his own dignity when driven to it, would object, or would at least chase the pigeons off, but he is utterly and catastrophically undone, overcome by exhaustion and racked with pain and fever and a blinding cold in the head, suffering now, he knows, that final apathy of limb that marks, against his choosing, the end of the cold staggering race which he's, willy-nilly, losing or however that old doggerel goes

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Pinocchio in Venice»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Pinocchio in Venice» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Pinocchio in Venice» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.