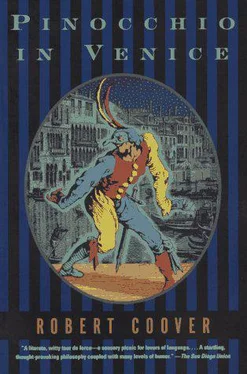

Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1997, Издательство: Grove Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Pinocchio in Venice

- Автор:

- Издательство:Grove Press

- Жанр:

- Год:1997

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Pinocchio in Venice: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Pinocchio in Venice»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Pinocchio in Venice — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Pinocchio in Venice», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

2. MASKED COMPANIONS

The Stazione Santa Lucia is like a gleaming syringe, connected to the industrial mainland by its long trailing railway lines and inserted into the rear end of Venice's Grand Canal, into which it pumps steady infusions of fresh provender and daily draws off the waste. As such (perhaps it is constipation, that hazard of long journeys, that has provoked this metaphor, or just something in the air, but its irreverence brings a thin twisted smile to his chapped lips), it is that tender spot where the ubiquitous technotronic circuit of the World Metropolis physically impinges upon the last outpost of the self-enclosed Renaissance Urbs, as a face might impinge upon a nose, a kind of itchy boundary between everywhere and somewhere, between simultaneity and history, process and stasis, geometry and optics, extension and unity, velocity and object, between product and art. One is ejected through its glass doors as through the famous looking-glass into a vast empty but strangely vibrant space, little more than a hollow echo of the magnificent Piazza at the other end of the Canal, to be sure, severe still in its cool geometry transposed from the other world and stripped of all fantastical ornament, but its edges, lapped at by the city's peculiar magic, are already blurred and mysterious, its lights hazed by a kind of furtive narcissism, its very air corrupted by the pungent odor of the nonfunctional. The corpulent Scalzi with its dingy overworked façade is, inarguably, little more than a morose impertinent shadow of its luminous counterpart at St. Mark's, the latter held by some authorities to be "the central building in the world" (and who is he, in search here of such an anchor, to dispute that? no, no, he accepts everything, everything ), and across the Grand Canal, instead of the placid grace and power of the Salute at the other end, there is here only misshapen little San Simeon Piccolo with its outsized portico and squeezed dome — but even these poor creatures are monuments to locus, place-markers, far removed from the current architectural glorification of airports, superhighways, and space flight, and thus a part of the immense integral Self that is this enchanted city, after all, the Scalzi's baroque façade a kind of Carnival mask, both revealing and deceptive, the popping green bubble on San Simeon the Dwarf rising through the fog with the erotic suggestion of a Venetian double entendre.

Below the long arching stone bridge upon which the eminent pilgrim now stands, having paused a moment at the crest to contemplate this crossing, as he thinks of it, into the dark congested but alluring labyrinths of his own soul, his own core, so to speak (and to catch his breath, rest his damaged knees, vent a bit of spleen, unfray his temper; that useless fat-bottomed cretin of a porter has been unable to pull the luggage up the bridge alone, the professor has been obliged to push from behind, and more than once on the way up he caught the wily old villain with only one hand on the trolley), there would ordinarily be, as he knows, even now in the winter, a bustling traffic of water buses, barges, gondolas, private skiffs and motor launches and sleek speedboat taxis, all of them swarming in and out of the busy docks and wharves with their delectable clusters of souvenir stands and news vendors and flower stalls like bees at the hive, loading and unloading goods and people, and circled about all the while by wheeling gulls and fluttering pigeons, a most exemplary spectacle; but now it is night and the Canal is hushed and empty, save for a single light bobbing indistinctly in the cold fog or perhaps at the far side of his failing vision and, in the echoey distance, the audible rumble of a lonely waterbus sidling up to a landing stage. Not that he would have it otherwise. Perhaps it is the art critic in him, but he likes the stillness of the scene before him, its aura of motionless eternity. It comforts him. And the silence, the fog, the gloom excite him. It is as though the city, momentarily hushed by awe, were genuflecting before not him, but the nobility and solemnity of his pilgrimage. Here I am, the city seems to be saying, in all my innocence and beauty. Within my depths lies that final knowledge you seek. Enter me.

"The world is made of stairs. Some people descend them and some climb them," remarks the porter ponderously, breaking the spell. "Unfortunately, sire, we must do both."

"Yes," sighs the professor, tearing himself away from his revery (he has just been overtaken by a vague sweet memory of another time, another arrival, back when real steamers plied these waters, ferrying passengers all the way from the distant mainland where the stagecoaches and donkey carts, caravans and carriages stopped, a delicious time fragrant with friendships pledged from the heart and ripe with the prospect of endless gaiety and supreme clarity, when for a moment everything made sense ), aware that the harsh icy wind has crept well inside his camelhair coat and professorial tweeds as though undressing him, preparing him for — for what? He prefers not to think about that. "I told you we should have taken a gondola," he adds crossly.

"In this weather? It is easier to find the sun at midnight, dottore," replies the porter, turning his masked eyes to the skies, which are black and heavy but faintly aglitter with damp reflected light swirling about in the wind. Below the paper snout, a long tongue lolls, seemingly real. The professor leans closer, not trusting his old eyes. "But come along now," exclaims the porter with a hasty slurp, slouching away into the shadows. "Let us pick up the old sticks, as they say, professore, it's just two steps away. You take the front end this time, and I'll — "

"What — ?! I'll do nothing of the kind!" storms the professor, outrage gripping him by the throat yet again. Really, this is too much! Moreover, that reference to old sticks has stung him to the quick. "I'm an old man, and desperately ill — I'm not allowed to lift anything! Do you hear? Are you a porter or are you not a porter? You've been hired for this job, and if you don't fulfill your obligations, I shall be forced to take the appropriate — !"

"Very well," the porter says with that mournful shrug of his, or rather has said somewhere in the middle of this lecture, pushing the trolley dutifully toward the edge of the steps meanwhile, his back bowed and nose bobbing forlornly, the professor realizing too late that his tirade, however justified, has perhaps been impolitic and interrupting it now to stumble weak-kneed toward the trolley in the vain hopes of arresting its further progress, only to see it slip out of the trembling hands of the porter and commence, just beyond his grasp, its catastrophic descent. As he clutches at the tipping trolley, his forward momentum propels him out over the lip of the stairs and into the empty space as though he meant to throw his own fate in with his cascading luggage, but the porter, with a sudden display of unwonted agility and strength, snatches him deftly by his collar and, pulling him back from the very brink, saves his life. "Mustn't throw the handle after the axe," the porter admonishes morosely, still holding the professor suspended above the top step and watching the bags tumbling as if in slow motion to the gleaming pavement far below. "If you can't save the cabbages, at least save the goat."

"I–I'm very grateful," the dangling professor whispers meekly, his heart in his throat where his regrettable rage once was, and receives, as though in reply, a stinging swat from the white cane of a blind bearded monk hurrying by. The monk, seemingly confused by this fresh information at the end of his cane, turns to swish wildly at the professor again, backs off the top step, misses the second, finds only the lip of the third, lands gingerly, cassock flying, on the fifth, his momentum propelling him to the seventh and eighth, where he strikes the one bag that has not tumbled to the bottom, and, his heels soaring gracefully now above his cowled head, completes his descent on all but his feet, yowling all the way down like a baby with colic or a cat in heat. At the bottom, where he seems to have landed on all fours, if he has four, the monk scrambles about in bewildered circles, searching for his cane, then, finding instead the professor's umbrella, rushes away without a backward glance, so to speak, disappearing down one of the dark foggy alleyways, his frantic tapping slowly trailing away into the night.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Pinocchio in Venice»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Pinocchio in Venice» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Pinocchio in Venice» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.