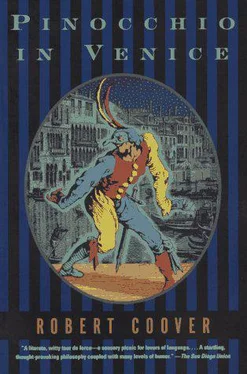

Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1997, Издательство: Grove Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Pinocchio in Venice

- Автор:

- Издательство:Grove Press

- Жанр:

- Год:1997

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Pinocchio in Venice: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Pinocchio in Venice»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Pinocchio in Venice — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Pinocchio in Venice», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Paolo Veronese, whose church this is, having claimed it in the end with his very bones (his funerary bust gazes sternly down from the wall behind his painted organ upon its sickly visitor, shivering in his pitiable rags, and admonishes him with its straight classic nose, its unpocked flesh, its handsomely draped breast, its noble and contented demeanor, looking much like the benign host of some great and sumptuous feast, from which the visitor, though he may ogle, is forever excluded), toys with this problem of the light's source in his central altar painting, in which Saint Sebastian's pierced groin is vividly lit up, but his tormented face is cast in shadow by the thick cloud at the Virgin's feet. She hovers just above him with the infant Jesus as though in someone else's vision, stealing the scene, as it were bathed in a golden Technicolor light not quite real and attended by angels fussing about like dressers, while the saint, his view obstructed (and looking a bit fearful that, what with all his other problems, something awesome might be about to fall on him), turns black with death and doubt.

Though it speaks in some ways to the abused traveler's embittered mood, this is not the classical Venetian Sebastiano. Veronese, as usual, has taken liberties. Traditionally the martyr is shown standing contented as a wooden post, bathed in golden light himself, and stuffed with arrows as though he might be sprouting them like twigs, an image that, while often ridiculed, once touched the professor deeply, especially as painted by his beloved Giovanni Bellini. The image — "a piercing of eternity's veil," as he called it — led him into his early Venetian monographs on traumatic transfiguration and on toys as instruments, simultaneously, of death and wisdom, and eventually lay at the heart of his controversial theoretical work, Art and the Spirit, the central theme of which was the absorption (the punctured flesh) of Becoming, fate, action, multiformity, naughtiness, discord, theatricality, bad temper, extrinsicality, evil companions, carpentry, negation, ignominy, and ultimately Art itself (the wooden arrows) by Being, will, repose, unity, obedience, peace, the eternal image, aplomb, intrinsicality, saints, teaching, affirmation, beatification, and all in the end by the transcendent Spirit (the languid gaze).

That languid gaze, he felt, had something to do with the mysterious shimmering light of Venice, a light that, paradoxically, seemed permanently to fix before the eye the very flux that excluded all fixity, patterns and archetypes emerging from the watery atmosphere like Platonic ideas materializing in the fog of Becoming, and so spellbinding the gazer in a process that more or less mirrored that of the moviegoer lost conversely to seeming life in the flickering sequence of lifeless film frames, movement there emerging from fixity, the viewer's rapt gaze seduced, not by eternal Ideas, but by illusory angels cast up by the enchantment of "persistence of vision," as they called it. And as he called it, too, when speaking of the Venetian masters, borrowing from the then-disreputable cinema industry, another revolutionary and controversial — "mischievous," as his adversaries bitterly remarked — critical act. The illusory, that is to say, was, for the great Venetian painters, what was real. Change was changeless, Becoming was Being. For them, "persistence" of vision was active, not passive: they saw through. Theirs was the art of the intense but reposeful acceptance of the turbulent wonderful.

This ground-breaking work, dismissed at the time as the "malicious prank of an irredeemable parricide," was to be sure an audacious frontal assault (though never, in obedience to the Blue-Haired Fairy's precepts, disrespectful to his elders) upon the established dogma of the day, a dogma that reduced Venetian painting to mindless decoration, mere theater sets for cultic spectacle, as it were, "unperplexed by naturalism, religious mysticism, philosophical theories" and "exempt from the stress of thought and sentiment," as the paterfamilias of aestheticians put it, but, disturbing as his youthful iconoclasm was, it turned out to be less controversial than the book's many alleged parallels with his own life story. In those long-ago days of faith still in progress and pragmatism, personality was seen as a hindrance to "pure science," and "spirit" of course was a dirty word, "I" anathema. He was accused of feeding, with works of art, "the great maw of a monstrous ego." His theories were ridiculed as "thin laminations, scarcely concealing a deep-rooted psychosis." "The confused work of a split personality," another said. "Dr. Pinenut cannot see the forest for the tree."

He could not entirely deny these charges. He was himself a product, after all, of his father's rude art and a transfigured spirit; the title had not come to him by accident. The quest for the abiding forms within life's ceaseless mutations was his quest, had been since he burnt his feet off; he too, rejecting all theatricality, sought repose in the capricious turbulence — freedom, as it were, from story. Even his decision to study the Venetians had to do with his own origins. If the beginnings of Venetian painting, as that same father figure of the priesthood who had dismissed Venetian art as "a space of color on the wall" argued, "link themselves to the last, stiff, half-barbaric splendors of Byzantine decoration," how could he help, pagan lump of talking wood that he once was, but be drawn to these magicians of the transitional? No, his reply to all these accusations in his germinal "Go with the Grain" manifesto was: "All great scholarship is a transcendent form of autobiography!" "It-ness," he declared (this was the first time he was to use the concept later to be made world-famous in The Wretch), "contains I-ness!" The victory was his. Even physics would never be the same again.

Oh, she would have been proud of him, she who had launched his great quest with her little Parable of the Two Houses, here on this very island, all those many years ago. He'd been cast up by a storm and was begging at the edge of town when she found him. She offered him a supper of bread, cauliflower, and liquor-filled sweets in exchange for carrying a jug of water home for her. He'd last seen her as a little girl, and moreover presumed her dead, so he didn't recognize this woman, old enough to be his mother, until she took her shawl off and he saw her blue hair. Whereupon he threw himself at her feet and, sobbing uncontrollably, hugged her knees. "Oh, why can't we go home again, Fairy?" he wept. "Why can't we go back to the little white house in the woods?" Her knees spread a bit in his impassioned embrace, and the fragrant warmth between them drew him in under her skirts. He wasn't sure he should be in here, but in his simple puppetish way he thought perhaps she didn't notice. He felt terribly sleepy, and yet terribly awake, his eyes open but filled with tears.

"Let me tell you a story, my little illiterate woodenknob," she said above his tented head, "about the pretty little white house and the nasty little brown house — do you see them there?" He rubbed his eyes and running nose against her stocking tops and peered blearily down her long white thighs. Yes, there was the dense blue forest, there the valley, and there (he drew closer) the little house, just hidden away, more pink than white really, and gleaming like alabaster. But the other — ? "A little lower " She pushed on his head, sinking him deeper between the thighs, until he saw it: dark and primitive, more like a cave than a house, a dank and airless place ringed about by indigo weeds, dreary as a tomb. She pushed his nose in it. "That is the house of laziness and disobedience and vagrancy," she said. "Little boys who don't go to school and so can only follow their noses come here, thinking it's the circus, and disappear forever." He was suffocating and thought he might be disappearing, too. She let him out but, even as he gasped for breath, stuffed his nose into the little white house: "And here is the house for good little boys who study and work hard and do as they are told. Here, life is rosy and sweet, and they can play in the garden and come and go as they please. Isn't that much better?"

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Pinocchio in Venice»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Pinocchio in Venice» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Pinocchio in Venice» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.