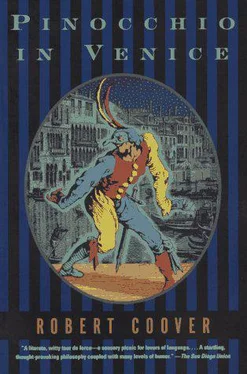

Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1997, Издательство: Grove Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Pinocchio in Venice

- Автор:

- Издательство:Grove Press

- Жанр:

- Год:1997

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Pinocchio in Venice: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Pinocchio in Venice»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Pinocchio in Venice — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Pinocchio in Venice», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Yet it was for her sake he has returned and, though deceived, he can pride himself that on this occasion his intentions at least were nobler: the search, not without considerable personal sacrifice, for the consummation, as it were, of a virtuous life — and yet, and yet, he cautions himself, stumbling along, wasn't that dream of an ultimate life-defining metaphor as mad as the dream of money trees? What was he hoping for this time, another Peace Prize? Beatification? Another review that lauded his wisdom and stylistic mastery, whilst scarcely concealing an annoyed amazement that he was still alive? Another invitation to receive an honorary degree and put his nose on view? As he trudges miserably, step by leaden step, through this city of masks, its very masks masked this morning by the snow blown against its crumbling walls like the white marble faces masking Palladio's pink churches, a dazzlingly sinister mask, today's, as expressionless and macabre as the Venetian bauta worn last night by the hotel proprietor, the alleged hotel proprietor (fakes within fakes, deceptions upon deceptions!), he feels the mockery cast upon his own shabby self-deceptions, the impostures and evasions, grand pretensions, the many masks he's worn — and not least that of flesh itself, now falling from him like dried-up actor's putty. Ah, he was right to come here, after all, old piece of rot-riven firewood that he is, to share his shame with the defrocked sheep and peacocks, the wingless butterflies and combless cocks of Fools' Trap.

As the despondent prodigal shuffles along, "carrying through," as he would say, but just barely, dragging one ill-shod foot laboriously through the snow, then, after a deliberating pause, the other, his patient companion trots back and forth, sniffing this canal railing, lifting his leg on that boutique wall or Carnival poster, nosing around in garbage bags and emptied crates, lapping at cast-off food wrappers and paper cups, as though to pretend that this is the unhurried way he always goes to work. The streets are empty but for a few angry red-faced women under their dark umbrellas, carried like missile shields, a midmorning drunk or two, flurries of wheeling black-faced gulls, the occasional lost tourist. The heavy metal shutters are down on most of the shops, intensifying the city's blank stare (it is this blank stare he has been feeling, this cold shoulder, this icy scorn — there are no reflections today, even the ditchlike canals full of dirty slate-colored water, scummed with snow, are opaque), but from those that are open — a baker, a newsstand, a pasta maker, a toyshop and a cantina, a pizzeria — Alidoro receives and returns greetings, picking up scraps of this and that to nibble on which the professor in his desolation refuses.

Once they've passed out of earshot, Lido fills him in on the politics, in-laws, crimes, calamities, debts, spouses and lovers, foibles, fantasies, and farces of each of the shopkeepers, keeping up a steady rumble of conversation as though to stop the old professor's brain from freezing up. "Started life as a gigolo for the local contessas, that one, helped manage one of their Friends of Venice flood rescue funds, rising as you might say while the Old Queen sank, and then, when his little bird died, he retired into politics for awhile and, after the usual scandals and piracies, ended up in fashion leather, security systems, and the manufacture of decorative window boxes. Careful now, old friend, not too close to the edge there " Lido talks as well about his career as a police dog, life in Italy between the wars, how the Fascists tore his tail off for some secret he never knew or couldn't recall ("You know me, I can't remember from the nose end of my muzzle to the other "), his irremediable attachment to this island in spite of his loathing of tourists and his lifelong fear of water ("I always meant to leave, but you can't straighten an old dog's legs my friend, I'll have to draw the hide in this infested overdecorated chamber pot, I'll fodder their boggy eelbeds in the end "), his hatred of the modern world with its electronically hyped-up homeless transients, all of them nowhere and anywhere at the same time, even when they think they're at home, the humiliations of toothlessness and blindness (the professor, absorbed in his own debilities, hasn't noticed; he notices now: the old fellow navigates largely by nose alone), and life with his "mistresses," as he calls them, women he meets getting arrested, who take him home with them when he gets them off, and who are grateful and treat him well until they get taken back in again.

"They seem to get some comfort out of an old dog. I do what I can for them. Not much, of course, but the cask gives what wine it has, as they say, and at worst I've got this old stub of a tail to get me by when I'm not up to better. Unfortunately, a lot of the old dears have taken a bad fold of late, gone onto the needle, and are dying off now with the plague."

"There's a plague in Venice — ?!"

"There's a plague everywhere."

In between stories, Alidoro, circling round and round in the bristling cold, asks the venerable scholar about his own career, about his books and his honors and his nose, about his prison days and life as a farm worker and getting swallowed by the monster fish ("You know what my father said when I went running up to give him a hug," he flares up, angry about something, though he can't say just what, "he said, 'Oh no, not you again, you little fagot! Even in this putrid fishgut I can't get away!' "), about his reasons for coming back to Venice (he doesn't give them — whatever they were, they were tragically stupid), about his problems with wood-boring weevils and fungal decay, and about America, about the bosses and the range wars, the recent elections ("How is it a country can stand tall, hunker down, sit tight, fly high, show its muscle, tighten its belt, talk through its hat, and fall on its ass, all at the same time?" the old mastiff wants to know), and the gangsters and centerfolds and dog catchers of Chicago.

Even though the professor is aware that his friend is provoking this dialogue as well-meant therapy against the despair which is threatening to halt him in his tracks, he cannot curb his sense of outrage and betrayal that he should be visited by such bitter despair in the first place — or the last place, as it were (and perhaps he even wants the despair, who knows, perhaps it is this that is making him crabby: he's earned it, has he not?), such that when Alidoro asks him: "How did you get so interested in painted pictures anyhow, compagno? I would have thought, wide-awake as you were — ", he cuts him off snappishly with: "Because they don't move. And they don't ask tiresome questions." He groans faintly, regretting the outburst, though Alidoro seems unperturbed by it, maybe even pleased, in that it has carried him another three steps or so. They are trudging past silent black-faced gondolas with silver beaks, now laden with snow as though trying to disguise themselves as squatting gulls. Actors everywhere. Who can you trust? "I'm not a greedy man, Alidoro. I learned early on from my father's pear peels, the pigeon's tares, the circus hay, to be happy with little in this life. I have given up much for that little. And the little I wanted, here at the end, was to finish one last chapter of one last book before I died. But now "

"Ah well, maybe that's a blessing," grumps the old dog. "Too many words in the world already. Like taking water to the sea."

"Enough words maybe," acknowledges the old scholar with a sigh, "but we still haven't put them together right. That, Alidoro, is our sacred mission."

"Bah!" barks Alidoro. "I shit on sacred missions!" And he squats right where he is in front of a barbershop to make his point.

"That's easy for you to say," replies the professor wryly, gazing blurrily upon the squatting dog. "If I try to make that kind of argument, your friends will want to throw me in jail again."

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Pinocchio in Venice»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Pinocchio in Venice» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Pinocchio in Venice» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.