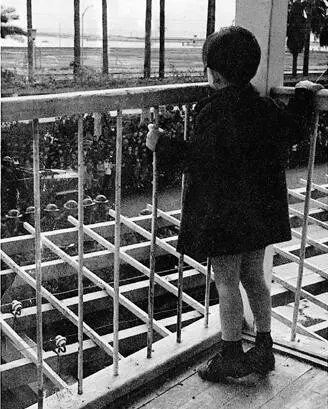

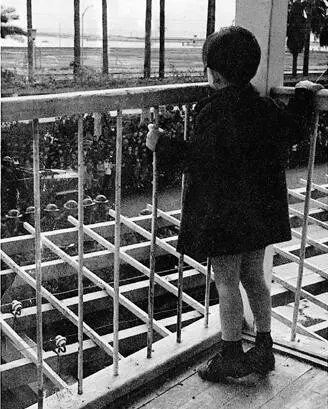

Me, watching a military parade in Mersin

We clip-clopped past the official house of the Vali (the provincial governor), past the monumental Halkevi (the House of the People) and its seaward-gazing statue of Atatürk, and then past the Greek Orthodox Church. At the rear of the church was the priest’s house. It overlooked an open-air cinema where shadows of bats flitted across the screen. I could not follow the films — I half-remember a tragic melodrama involving disastrous migrations from country to city — or why the paying public, massed amongst winking red cigarette tips, intermittently snapped into fierce, sudden applause, the men rising from blue wooden chairs to clap with frowning, emotional faces. Peering through the rear window with my great-aunt and the priest’s family, I looked out on a world full of stories I did not understand.

After the Greek Orthodox Church, the carriage jingled past big merchants’ houses, some semi-abandoned, most in disrepair. In the top corner of each, it seemed, lived an old lady whom one knew — Madame Dora, Madame Rita, Madame Fifi, Madame Juliette, Madame Virginie. It was a leafy street, and turtle doves purred in the trees. On we went, hoofbeats clacking, the gentle stink of horse-shit wafting up from the street, until we came to Camlibel (pronounced Chumleybell ), a small oval park surrounded by villas with gardens that overran with fruit trees and bougainvillaea. At the far end of Camlibel was the Dakad residence, a large, cool, rented apartment on the first floor of a villa. Tante Isabelle’s place was only a little further on, just before the military barracks at the edge of the town. That was the long and the short of Mersin in those days: a quarter-hour ride in a carriage, or a five minute drive for a slow-moving car such as the van transporting the body of Joseph Dakad to Camlibel.

If you drove out west of Mersin, you travelled along a beautiful coastline. Once you had passed through the avenue of palm trees by the barracks, crossed the dry riverbed and gone past the stadium of Mersin Idmanyurdu (the football team that has always yo-yoed between Turkey’s first and second divisions), in a deafening roar of frogs you came upon mile after mile of orange groves and lemon groves planted, at their perimeters, with pomegranate, grapefruit, tangerine and medlar trees. Then came the villages of Mezitli and Elvanli and Erdemli, the Taurus foothills meanwhile getting closer and closer until, after you’d motored for the best part of an hour, the farmland expired and the road was hemmed in by, on the left, the sea — which indented the land with bays that flared turquoise at their confluence with freshwater streams — and, on the right, rocks covered with wild olive trees, sarcophagi, basilica, aqueducts, castles, arches, mosaics, ruined temples and ghost villages. You drove on until you came to Kizkalesi, an island fortress wondrously afloat three hundred yards offshore that is a relic of the medieval kingdom of Lesser Armenia, and you got out of the car and went swimming in hot, lucid waters. There was nobody else around except for the occasional camel or shy children hoping to be photographed.

In the last twenty years, the beach holiday has arrived in Turkey. Nowadays Kizkalesi is a swollen, chaotic resort crowded by tourists from Adana and the landlocked east. The roadside antiquities are dwarfed by advertising hoardings, pansiyons and summer homes, the inlets and creeks are covered by a mess of unplanned structures, the citrus groves have been razed to make way for holiday complexes and towering, gloomy suburbs. The belching frogs have gone (some, decades ago, packed in ice and shipped by Oncle Pierre to the tables of France), and an hour’s drive will barely take you clear of Mersin’s concrete outskirts and the moan of cement-mixers and the fog of building dust.

In Mersin itself, a huge boulevard now swings along the seafront. Countless young palm trees spring from the pavements, new stoplights regulate the chaos at junctions, traffic islands are dense with flowering laurels, and block after block after block of bone-white apartments take shape from grey hulks. Hooting minibuses race through the streets three abreast, residential complexes multiply along the coast, the minarets of enormous new mosques make their way skywards in packs. In the final thirty years of the last century, the population, swollen by a massive influx from the east, much of it Kurdish, has multiplied sixfold to around six hundred thousand. It’s a boomtown. The port, with its officially designated Free Trade Zone, ships’ commodities worldwide in unprecedented quantities: pumice-stones from Nev  ehir to Savannah and Casablanca; pulses from Gaziantep to Colombo, Karachi, Chittagong, Doha and Valencia; apple concentrate from Niğde to New York and Ravenna; TV parts from Izmir to Felixstowe and Rotterdam; insulation material from Tarsus to Alexandria and Abu Dhabi; dried apricots from Malatya to Antwerp (and thence Germany and France); Iranian pistachios to Haifa (in secret shipments, to save political embarrassment); Russian cotton to Djakarta and Keelung; citrus fruit from Mersin to Hamburg and Taganrog; synthetic yarn from Adana to Norfolk and Alexandria; carpets from Kayseri to Oslo and to Jeddah. Just along from the new marina, you’ll find a Mersin Hilton and luxury seaside condominiums; and in the unremarkable interior of the city, the gigantic Mersin Metropol Tower (popularly known as the dick of Mersin) lays claim to the title of ‘the tallest building between Frankfurt and Singapore’. On the streets, young women are turned out in European trends, teenagers smooch, and male students at the new Mersin University amble along Atatürk Çaddesi, Mersin’s first pedestrianized street, with long hair and clean-shaven faces.

ehir to Savannah and Casablanca; pulses from Gaziantep to Colombo, Karachi, Chittagong, Doha and Valencia; apple concentrate from Niğde to New York and Ravenna; TV parts from Izmir to Felixstowe and Rotterdam; insulation material from Tarsus to Alexandria and Abu Dhabi; dried apricots from Malatya to Antwerp (and thence Germany and France); Iranian pistachios to Haifa (in secret shipments, to save political embarrassment); Russian cotton to Djakarta and Keelung; citrus fruit from Mersin to Hamburg and Taganrog; synthetic yarn from Adana to Norfolk and Alexandria; carpets from Kayseri to Oslo and to Jeddah. Just along from the new marina, you’ll find a Mersin Hilton and luxury seaside condominiums; and in the unremarkable interior of the city, the gigantic Mersin Metropol Tower (popularly known as the dick of Mersin) lays claim to the title of ‘the tallest building between Frankfurt and Singapore’. On the streets, young women are turned out in European trends, teenagers smooch, and male students at the new Mersin University amble along Atatürk Çaddesi, Mersin’s first pedestrianized street, with long hair and clean-shaven faces.

Of course, some things never change. Sailors still sport snowy flares. Men wear vests under their shirts in the clammy August heat, and moustaches, and old-fashioned trousers with a smart crease leading down to the inevitable dainty loafer. You’ll still see vendors pushing carts loaded with pistachios, grapes, or prickly pears; corn on the cob (grilled or boiled) is sold at street corners; and shoeblacks grow old behind their brassy boxes. The old vegetable and meat and fish market has kept going, and the pleasant little Catholic Church of Mersin where my parents were married and which I have intermittently attended over the years is the same. As ever, a fountain spurts a loop of water in the church’s small, leafy courtyard, and Sunday Mass attracts adherents to all six Catholic rites — Roman, Syrian, Chaldaean, Maronite, Armenian, and Greek. It’s a varied congregation. You’ll see ageing westernized Christians in drab urban clothes, enthusiastic children packed in scrums into the front pews (boys right of the aisle, girls left), and a big turn-out of worshippers vividly dressed in shawls and baggy pants; these last are Chaldaeans from the mountains in the extreme south-east of Turkey. Not all Mersin Christians are rich.

But old Mersin — the Mersin to which my grandfather’s body returned, a town of verandas, gardens and large stone houses — has largely disappeared. One by one, the villas have been sold, knocked down and replaced by tower blocks. The last surviving villa of the Naders, my grandmother’s family, is in Camlibel. The fate of this elegant building, which until only a few years ago was occupied by my mother’s cousin Yuki Nader and his Alexandrian wife, Paula, is not atypical. Surrounded on all sides by tower blocks whose occupants bombard it with junk, it is boarded up and empty — awaiting the bulldozer or, I’ve heard it rumoured, conversion to a bank — its avocado trees, shutters, gates, even its footpath stones, ripped out by persons unknown. Nobody seems to notice or, more precisely, attach significance to this spectacle.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу

ehir to Savannah and Casablanca; pulses from Gaziantep to Colombo, Karachi, Chittagong, Doha and Valencia; apple concentrate from Niğde to New York and Ravenna; TV parts from Izmir to Felixstowe and Rotterdam; insulation material from Tarsus to Alexandria and Abu Dhabi; dried apricots from Malatya to Antwerp (and thence Germany and France); Iranian pistachios to Haifa (in secret shipments, to save political embarrassment); Russian cotton to Djakarta and Keelung; citrus fruit from Mersin to Hamburg and Taganrog; synthetic yarn from Adana to Norfolk and Alexandria; carpets from Kayseri to Oslo and to Jeddah. Just along from the new marina, you’ll find a Mersin Hilton and luxury seaside condominiums; and in the unremarkable interior of the city, the gigantic Mersin Metropol Tower (popularly known as the dick of Mersin) lays claim to the title of ‘the tallest building between Frankfurt and Singapore’. On the streets, young women are turned out in European trends, teenagers smooch, and male students at the new Mersin University amble along Atatürk Çaddesi, Mersin’s first pedestrianized street, with long hair and clean-shaven faces.

ehir to Savannah and Casablanca; pulses from Gaziantep to Colombo, Karachi, Chittagong, Doha and Valencia; apple concentrate from Niğde to New York and Ravenna; TV parts from Izmir to Felixstowe and Rotterdam; insulation material from Tarsus to Alexandria and Abu Dhabi; dried apricots from Malatya to Antwerp (and thence Germany and France); Iranian pistachios to Haifa (in secret shipments, to save political embarrassment); Russian cotton to Djakarta and Keelung; citrus fruit from Mersin to Hamburg and Taganrog; synthetic yarn from Adana to Norfolk and Alexandria; carpets from Kayseri to Oslo and to Jeddah. Just along from the new marina, you’ll find a Mersin Hilton and luxury seaside condominiums; and in the unremarkable interior of the city, the gigantic Mersin Metropol Tower (popularly known as the dick of Mersin) lays claim to the title of ‘the tallest building between Frankfurt and Singapore’. On the streets, young women are turned out in European trends, teenagers smooch, and male students at the new Mersin University amble along Atatürk Çaddesi, Mersin’s first pedestrianized street, with long hair and clean-shaven faces.