Two pairs of hands

He made himself a refreshing drink of water and sour grape squeezings, only he had forgotten how bad the water tasted (it came from the muddy ditch) and how much worse it tasted in that corroded, dirty tin cup, to say nothing of the fact that the grapes actually weren’t so good, either.

As they walked along the mountain trail, butterflies settled and rose in the sand, fanning their wings like helicopters. The guerrilla beside the Young Man took his hand, the palm of it, the soft flesh of it, between two fingers, pinching it and working it. — “Why … like this?” he said. “You not strong.” —The Afghan’s hand was dark and hard, like a new walking shoe that hadn’t been broken in. — The Young Man was not ashamed. “I do different things in America,” he said. “I read, write, push buttons. You dig, plow, shoot.” —The guerrilla said nothing.

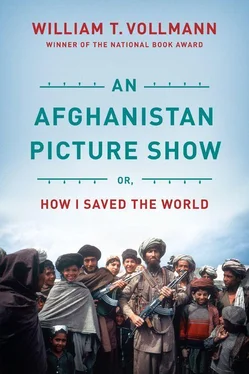

An Afghanistan Picture Show [3]

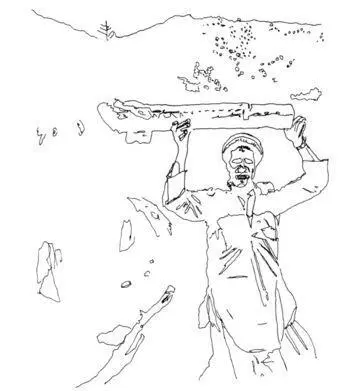

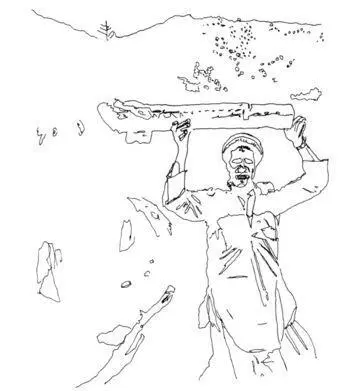

Seizing the charred stump of a rocket bomb, a Mujahid raised it high above his head and turned to face the Young Man, his eyes shining fiercely as if to say: This is why you came! Now look, look! Your business here is to see! See this, and understand it; never forget it! and the Young Man stood looking at the man’s leathery reddish-brown face, the cheeks drawn up in effort as he held the bomb high, the parted lips, the even white teeth, the graying hairline just below the double-lipped prayer cap, the shadow of the bomb falling from shoulder to shoulder, those upraised arms in which the bomb casing lay khaki and black and orange-rusted, rusted through in places so that the Young Man could see the skeleton grid beneath the shell (it must have been a dud), and the bomb hung eternally in the air and the Mujahid’s cotton shirt hung down and the river flowed clear and shallow behind him, leaving undisturbed the white rocks that lined it, and the hills were tan with dry grass, green-spotted here and there with a bush or a tree, and the other Mujahideen had also turned and were staring at the Young Man as the bomb stared at him and he stared back and said to himself: Whether or not I can do anything useful, at least I will remember.

In so many frames of my Afghanistan Picture Show I see the men in wildly various caps grinning at their guns and cradling them, uplifting them among the tree-pocked mountains, loving them, pointing them, holding them like guitars, the bullets long and gold and heavy together in cartridge belts sweeping down shoulder and chest; each laughing at the sight the others made, each looking at his Kalashnikov or Lee-Enfield or Springfield with shy fondness because the weapon was a dream like a son was a dream; ethe weapon was a dream of revenge.

And I also see those Pakistanis and Afghans leaning forward into the tape recorder, talking and talking emphatically, some hoping, some desperate, some without expectations, just helping me to understand. — What a daunting thing RECOGNITION is.

The red hill [6]

It rained there every day at a little past twelve. The result was to raise more dust. It always stank of dust there, a metallic, choking, dirty taste in the throat like you might expect to get after kissing someone who’d worked for twenty years in a tombstone company or a cement factory. Everybody coughed all the time. It was no wonder, the Young Man thought, that Pushtu speech has so many t ’s and s ’s and kh’ s; if you are going to hack, why not make use of it? Maybe people with the same disease ought to get together to communicate with their spots.

Every time it rained the rooster crowed.

The men sat around in their baggy white shirts and trousers, spitting.

The Young Man hated the flies. There were always dozens of them on him, with at least two or three on his lips and eyes.

To console him, Poor Man went and got him some peaches. — “Go back to Peshawar,” he said. “Tell them, send strong American.”

“You want I go to Peshawar?” said the Young Man angrily.

“I want you see the fight. I want you go to city, see dead Roos . But you”—he pointed to the Young Man’s legs—“no good.”

Across the river gorge, a few clouds lay over a grubby reddish hill. There were trees on the hill; there was agricultural terracing; there were flies there, and a smell of dust, bomb debris and one tiny spring. There was a wide and easy path up the hill, but the guerrillas told him that an alootooka fhad flown over it and dropped butterfly mines there. So to climb the hill you had to ascend a steep slope of loose rock. On the summit of the hill were many trees, and empty Russian food tins. It was here that the war zone really began. Looking discreetly through the tree branches, you could see Afghanistan ahead, a desert dream of sand dunes and hazy dunes spread out far below, for this was the edge of the mountains. It was like a map that kept unrolling in the sun, with its bright baked canyons and oases and villages showing forth on the plains as if they had been painted there.

To the left of where the Young Man stood, the hill continued on to a ridge that made a right angle and ended in a spur, like an arm and fist extended from a man’s shoulder. The ridge was bare. It was very dangerous to go out on it. It had been torn by rocket shells. It was explained to the Young Man that if you went out on it, the Roos could see you.

Just on the horizon were six black dots in the middle of a village.

Suleiman guided the Young Man’s eyes to them. — “Roos,” he said. The Young Man peered through his telephoto at 600 mm. — Sure enough. Six tanks. — He looked at them for a while. Later he and Suleiman went down to the spring, and Suleiman gathered for him little sour yellow peaches and the tutan fruits, although it was still Ramazan and Suleiman could not eat. Suleiman smiled happily to see him eat. —“Malgurae,” the Young Man said. — Friend. —“Malgurae,” Suleiman said, and gripped his hand.

He had finally gotten to like the food. The morning after they had arrived, Poor Man had made him breakfast with his own hands: two eggs fried for a few seconds in very hot oil (so what he had, then, was a glass bowl full of hot oil, with the eggs diffused through it in curds of greater or lesser size) and a hunk of bread to eat it with, salted cucumber slices and tea saturated with sugar. It all tasted good. He was very hungry.

Every day a boy sneaked him dried apricots and tutans beneath his armload of kitchen onions. The Young Man took himself off to eat them. In midafternoon the Commander in Blue, Poor Man’s lieutenant, would fix him beef kebab and sweet green tea. An old man brought him a double handful of almonds. Later he found out that they were not almonds after all, but the nutlike kernel of the zwardailoo. g

“Much rain tomorrow?” he asked the Commander in Blue. Poor Man had gone into the chakar to meditate and pray.

“Kum-kum,” said the Commander in Blue. “ Leg-leg . Fifty-fifty.”

He went up to the top of the red hill again. The tanks were still there. From nowhere he felt a hand on his shoulder. A Mujahid smiled at him. There was always someone on watch here. — The Mujahid asked him to take his picture. When he obliged, the Mujahid was very happy and honored. It did not matter that he would never see the picture. He stood there with his Kalashnikov and smiled. Later he gathered a bunch of wild grapes for the Young Man. The Mujahid’s lips were chapped with dry dusty thirst, for it was still Ramazan, but he insisted that the Young Man eat the grapes there. (If he ate them, he would not be as good as the Mujahideen were. If he did not eat them, friendship would be insulted.) They tasted so sweet, so refreshing; he ate them and was ashamed.

Читать дальше