His four companions slept beside him, their rugs thrown over their faces to keep off the flies. The Young Man was not sleepy. So, squatting at his side, the malik entertained him. He was an old man with two rifles — one Chinese and one Indian; each was kept loaded with a clip of thirty bullets.

“You are Mujahid?” said the malik. They spoke in Pushtu, which required the Young Man to go to the grammatical heart of things every time.

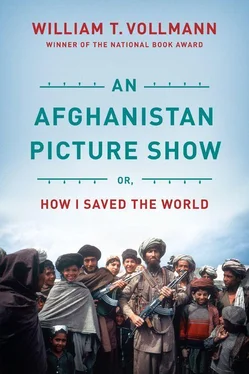

“No,” he said. “I Ameriki. I want to help Afghan Mujahideen. I come, take photos, bring photos to other Amerikis, and they see, they understand Mujahideen, understand refugees, maybe send rupees for Kalashnikovs, bullets, Ameriki guns, owuh dazai .”

An owuh dazai was a seven-shooter, a Lee-Enfield rifle. He had learned the word from a century-old manual for soldiers of the British Empire. It was probably hard to find an owuh dazai these days, but the Young Man had to do what he could with his vocabulary.

“You go to shoot at the Roos?” said the malik slyly.

The Young Man had hardly fired a gun in his life. “If Roos shoot at me, and Mujahideen give me topak , I shoot at Roos . But I am no good shot.”

The malik grinned. “I also no good shot. My father, he come from Afghanistan; he can kill. I am like you, just C.I.A., just tourist.” —He took the Young Man to the window. A thousand yards away, a goat was grazing among the rocks. The old man fired two shots almost simultaneously. Two puffs of dust appeared, one on either side of the goat. The goat leaped and ran.

“Very good,” said the Young Man, feeling it incumbent on him to say something. “Very good.”

The malik radiated delight. He got up and brought his guest some very good bread, made of thin, crackly, buttery layers. You rolled it in sugar and broke off pieces to dip in your chai . They offered him tea constantly. He was the only one who could legitimately eat and drink during the day. At least (fortunately for those who kept Ramazan) it was cool. The valley was at about 4,500 feet. Its sides were terraced with green rice paddies. Through the window he could see the snow on the mountains they would have to go through to cross into Afghanistan.

He had diarrhea as usual, his eyes hurt, and nobody would leave him alone.

“Sind chai wushka?” they asked him. Do you want river tea?

“Nuskam,” he replied. Don’t want. He went out and walked up to the cemetery, which was where everybody relieved himself, and had diarrhea.

THE FOREIGN LINGUISTS

The children understood his Pushtu the best, perhaps because they had not adopted one accent forever. It seemed that a man from one village might have trouble understanding a man from a village twenty miles away. The General’s son Zahid once told the Young Man that his family missed one word in five of the Brigadier’s speech. It must have been even more difficult to understand the Young Man, who had gotten his Pushtu only out of an old book. *—The children were willing to make an effort with the Young Man because he was a novelty momentarily eclipsing their other recreations, which consisted (I am of course speaking of the male children, for I never saw the other kind doing anything but hard work) of spitting, gathering apricots, listening to the men talk beneath the trees, and punching each other. The men watched and laughed. The more impudent the boys were, the more the men liked it. The boys would gather around the circle of men at the end of the afternoon and begin spitting. They would spit closer and closer to the men’s feet. Finally they would just miss someone’s feet, and the men would scold them sternly. The one who had been scolded would be punched by the others. The men deigned to chuckle.

The four Mujahids with the Young Man believed that if he couldn’t understand something they’d said, all they had to do was yell it loud enough. When that didn’t work, they were angry and dismayed. One of them, Muhammad, could read. In Peshawar the Young Man had bought an English-Pushto dictionary. When they had something to communicate to him that he could not understand, Muhammad scanned the pages until he found a very rough equivalent for what he wanted to say (a procedure which, since the words were arranged entirely according to their counterparts in the Young Man’s alphabet, took Muhammad a long time), and put his finger on it. The Young Man, who could not read Pushto, would say the corresponding English word aloud, as if Muhammad could somehow tell him whether this was the one right word out of millions; and Muhammad always nodded. — They thought he wasn’t happy. After flipping through the English-Pushto kitab for a quarter of an hour, Muhammad pointed to a word at last. — “Tragic,” the Young Man interpreted aloud. — Muhammad smiled at him like a psychiatrist. “ Tuh [you] tragic,” he said sympathetically. “Do you understand my speak, Mr. William?” —“Na,” dissented the Young Man heartily. “Kushkal, kushkal.” —Happy, happy. Of course he would be even more kushkal if they ever crossed the border, if they came back alive, if his rehydration salts held out, which they wouldn’t — oh, he was an unhappy, even tragic Young Man, he was! They had been here for days, waiting for Poor Man, the guerrilla leader, to show up with the ammunition. †

One afternoon the Young Man wanted to go out and take pictures of the mountains. They told him he couldn’t do that. Muhammad borrowed his English-Pushto kitab again and went off into a corner with a new arrival who knew a little English. Finally, beaming, they brought him back a note:

Not — the chawkar

becose this pipol is jahil

you is DAY Doyuo my

spieke M.R. — Uuiliam—

becose this pipaeli is not

have ajoucatan—

because this pipole is impolite

he spieke cam say topak .

In other words, said the Young Man to himself, interpreting the text like the student of comparative literature that he was, “Not the hills, because this people is ignorant. You is DIE. Do you understand my speak, Mr. William? Because this people is not have education; because this people is impolite; they say that your camera is a gun.” —Well, it was certainly nothing to DIE over, so he stayed indoors. It was all getting on his nerves.

The two men of the house kept picking up their rifles every day, taking them outside into the town and returning half an hour later with expressions of deep contentment. The Young Man looked up the word for “hunt” and asked Muhammad if that was what they were doing. — Muhammad laughed, pointed at the Young Man, and said, “Jahil.” —Ignorant. — Then he pointed at the malik and his gun. He perused the English-Pushto kitab and pointed to a word. — “Hostile,” the Young Man read.

(Surely they didn’t kill people for half an hour every afternoon? He never found out what they did. Maybe it was like one of those American Civil War parades.)

THE SECRET OF OUR SUPERIORITY

On the morning of the next day, ten Mujahideen came in, and the Young Man packed up quickly, but they only stretched out to sleep. That afternoon they pulled some refugee medicines from their baggage and asked the Young Man to explain the labels. The Young Man did his best, and they noted down his words beside the English names. One of the Mujahideen took a capsule of oral tetracycline, opened it, and poured its yellow powder onto a blister, which he had first prepared for treatment by rubbing it with a matchhead. They went through all the medicines, opening tins and packets which should have been kept sealed until use, and doling them out — a handful of painkillers, antibiotics and B vitamins per man, all tossed together in a length of previously sterile bandage. They asked the Young Man if there was anything to make them strong. One of the doctors in the camps had told him, “Every Afghan believes American medicines will turn him into a superman.” —The Young Man knew that they would hold it against him if he refused to disclose the secret. Reflecting on the diet of the traveling fighter — a piece of bread, a raw onion, a lump of hardened sugar and a cup of tea — he decided that it was ethical to point to the B vitamins, which he did. They were all happy. They asked him how many to take. Fancying himself a great social liberator, he said one a day for them, and two a day for the women and children. All the men immediately took two.

Читать дальше