He had been drinking. He lowered the glass, then reached to the table and set it down. “Just what is that supposed to mean, huh?”

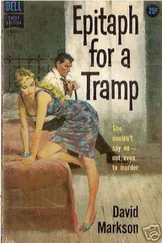

“Nobody walked you as far as Vinnie’s,” I said without emphasis. “Maybe I didn’t make it clear to the police, but you came in there on the dead run. It doesn’t prove anything about the killing — just that for one reason or another both you and Peters are lying.”

“Why, you son of a—”

His face got livid. June Allyson could have made herself look more ferocious with a minimum of effort, and I was a little sorry I had badgered him. I had simply been thinking out loud, and there wasn’t any real reason for it.

“So run the hell back and tell them,” he snarled then. “Don’t you think they checked the story? What’s it your business anyhow, you—”

I didn’t answer him. I was chewing on a knuckle awkwardly when someone tapped me on the shoulder. I started to turn, thinking that it was probably Henshaw.

It was Mount Everest.

It fell on me.

I caught it flush on the jaw. I staggered back three or four drunken steps, flailing my arms, but that was only for effect. I crashed down like something miscalculated at Cape Canaveral.

A thousand lights came on. They kept bursting like expanding stars. I was the only one seeing them.

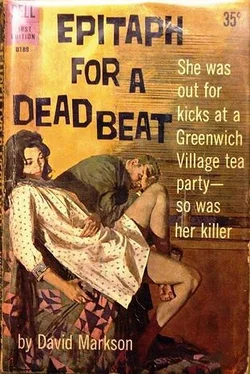

All by myself on the floor of a seedy Greenwich Village basement, and I was forging ahead of whole nations in the race for outer space.

I had a remote idea that the party had come to an abrupt halt. “Well, for crying out loud!” someone screamed. “I saw that, Pete Peters! Why, that man wasn’t even looking at you, you brute!”

Good old Donnie McGruder, just the ally I needed. I couldn’t make him out in the mists. All I could see was a bearded monster nine feet tall, with forearms like hams and shoulders like a yoke.

Nobody had told me Peters was nine feet tall. That worried me. I closed my eyes tightly and shook my head before I let myself look at him again.

So it was only six feet. So I’d still never get up there without help.

I didn’t want to get up anyhow. Let somebody else go climb mountains just because they’re there. I didn’t have any spirit of adventure. I didn’t have any pride either. I just sat, sucking in air.

“You’ve got some damned nerve,” McGruder was sputtering. “Now just what was that all about?”

“Aw, he was bugging Ephraim,” Peters said. “Giving the poor kid a hard time. After Ephraim spends two days in jail, for gosh sakes.”

“That’s still no reason to sneak up behind a man and hit him,” McGruder said. “Especially you, you big ape. Why, you might have killed him.”

It was me they were talking about. That was nice. Even Ephraim was interested. “He had it coming,” he contributed brightly. He was dancing around as gaily as a doll on a string. “He’s that private detective who found Josie the other night. What’s he butting in down here for anyhow? Maybe that will teach him to stay where he belongs, the carpetbagger.”

“That’s not the point,” Peters said. He had a remarkably soft voice for a big man, a voice like marshmallows toasting. Soft and gooey, like my head. But that was nice too. I found comfort in his marshmallowy tones.

I got myself lifted to one knee, with all the cosmic temerity of a creature emerging from a Darwinian swamp.

“Nobody should bother Ephraim,” Peters went on. “Two days in jail is enough. Ephraim suffered. Do you people have any concept of how he suffered? It makes him — why, it makes him holy.”

“So get him a tin cup, like,” somebody put in. Good old Henshaw also. “He can go beg alms.”

“It isn’t something to joke about,” Peters told him. “You people don’t comprehend the alchemy of it. Being in jail does something to a man’s soul. Something ultimate.”

“It makes him a saint,” I said then. “I’m sorry, I didn’t know I was intruding upon a religious awakening. Fact is, I must have come to the wrong party altogether. I was looking for the protest meeting about Sacco and Vanzetti. Whatever became of Sacco and — oh, sure, poor old Sacco and Vanzetti—”

People were looking at me strangely. It didn’t mean a thing. They were just disturbed by the sound of my scrambled brains. They kept sloshing around in the pan when I got to my feet. I hadn’t known I was going to say a word.

“What were we talking about?” I said. “Oh, yeah, oysters. I always thought they were fish myself. Actually I like toasted marshmallows better. No I don’t either. Ha! Come to think about it — you know what, about toasted marshmallows?”

“Say, listen, fellow — are you all right?”

That was Peters. He was watching me with genuine concern. I laughed in his face, swaying like a lunatic. I hadn’t known I was going to laugh either.

“Listen, there are beds out back, maybe you better—”

“No, no, first ask me — what about toasted marshmallows—”

“Sure,” Peters said. “Sure. You take it easy now, fellow.” He glanced past me, nodding anxiously to someone. “You want me to ask you about toasted marshmallows. Sure. What about toasted marshmallows, fellow?”

I grinned at him. “They make me nauseated,” I said. Then I hit him dead in the middle of that beard with as hard a left hand as I had ever thrown in my life.

Somebody gasped, but it wasn’t Peters. His head jerked, but for a second his body hardly moved at all. Then he went over like a felled oak.

A girl decided to shriek. Peters took two or three ringsiders with him, going back. One of them was Ephraim. I didn’t break up about it. The girl I’d spoken to before with the unmowed black hair and the figure like an ironing board was another one. She wound up sitting spraddle-legged with her mouth open and Peter’s head in the lap of her black skirt. She had on black stockings that ended just below her bony knees.

A man snickered. “The ultimate, man,” a woman added profoundly.

I was still pulling in air a little desperately. I waited another moment, watching until Peters came up groggily on one elbow. A fellow astronaut. His head dropped onto his chest and someone accommodatingly dumped the contents of a beer glass onto it. Ephraim was still sitting there also, staring at me in sullen outrage, as if I’d just maligned James Dean.

The mob had begun to chatter again and I pushed through them toward the bar. I didn’t see Henshaw or Fern, but McGruder took me by the arm. He gave me a precious, shy smile, the fairy princess I’d just won in the lists.

“I’m sorry about that, Harry. Dreadfully sorry. You must think we’re all beasts.”

“Forget it. I hope it didn’t bust up the party.”

“Say now, say, you forget it. You’re most welcome. If anyone should leave it’s Pete. That — that—”

He was leading me toward a corner. I didn’t have the strength to fight it.

“You are a private investigator, Harry?”

“I think somebody hung a sign on my back.”

He didn’t smile. In fact when I glanced at him I realized he had discarded almost all of his mannerisms. He was picking at a corner of his thin lower lip, and the serious expression made him look unexpectedly older.

“This is all very puzzling,” he said after a minute. “If not to mention tragic. I knew poor Josie Welch quite well. She was so young that I was something of a — well, a big brother to the girl. She used to come to me with her problems.”

I was working my jaw. “Any problems the cops would be interested in?”

“Oh, no, nothing like that at all. Just her bad childhood, general depression — psychological problems more than any other kind. She was raised on a farm in Kansas. The poor kid was attacked criminally by an uncle when she was no more than fourteen. It soured her on men pretty badly.”

Читать дальше